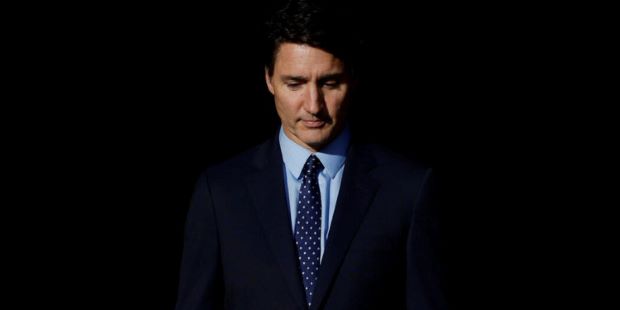

How Canadians fell out of love with Justin Trudeau

By Matina Stevis Gridneff

TORONTO — Canadian politics are getting fiery.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, the young scion of a Liberal family who swept the global political scene off its feet a decade ago, is now a 52-year-old leader with approval ratings worse than President Joe Biden’s.

He is rapidly losing ground to the Conservative Party’s leader, Pierre Poilievre, who, despite having vague policy plans, has deployed punchy sloganeering that has kept Trudeau on the ropes.

On Wednesday (25), the Liberal Party was set to face a vote of no confidence in Parliament. While the vote was expected to fail, it was a sign of deepening trouble as the party — like Trudeau — teeters months away from a general election.

After years of high inflation, soaring housing costs and an overstretched public health system, Trudeau faces abysmal polling numbers. Fewer than one-third of Canadians believe he’s doing a good job. More than 70% say Canada is “broken” under his leadership.

Poilievre, who uses tough rhetoric and promotes himself as a common-sense solution finder, has led Conservatives to a double-digit lead over the Liberals — even though many Canadians recently told pollsters that they wouldn’t be able to pick him out of a line-up.

Poilievre, 45, likes to keep his messages under three words, and they usually rhyme or are alliterative: “Spike the hike!” “Ax the tax!”

He and his team use social media heavily, borrowing tactics and tone from Donald Trump’s playbook, and often deploy incendiary language that feels out of place in Canada’s political discourse.

Trudeau is trying to stay above the fray. Despite his travails at home, he travelled to New York this week for the United Nations General Assembly, and on Monday (23) he sat down for an interview with late-night TV host Stephen Colbert.

“People are frustrated, and the idea that maybe they want an election now is something that my opponents are trying to bank on because people are taking a lot out on me for understandable reasons,” Trudeau told Colbert.

“I’ve been here, and I’ve been steering us through all these things,’’ he said, “and people are sometimes looking at change.”

We Need to Talk About Justin

While Canada staged a solid economic recovery after the coronavirus pandemic, and inflation is down to 2% from over 8% two years ago, those achievements have not earned Trudeau many political points.

Unemployment rates remain high, housing in major cities like Toronto is unaffordable and Trudeau’s government has been criticized for inviting too many foreigners to work in Canada over the past three years, putting pressure on infrastructure and services such as health care.

Yet, Trudeau’s most serious liability could be that he has been in power for too long and that he has lost the ability to market one of his most distinctive attributes: optimism.

“The government has come into trouble of its own making, in losing faith in its positive case for the country,” said Gerald Butts, the vice chair of Eurasia Group, a consulting firm, and a former top adviser to Trudeau and his party. “They have been overwhelmed by the message that the country is broken and have not been able to say the opposite.”

High-profile departures from the Liberal Party also give a sense that allies are abandoning a wounded Trudeau.

This month, the Liberals lost the backing of a smaller party — the New Democrats — that had given them a majority in the lower house of Parliament. The loss has left the Liberals vulnerable to challenges by the Conservatives, including Wednesday’s vote of no confidence.

There has also been an exodus of officials and senior politicians from Trudeau’s party. The Liberals’ national campaign director resigned this month, citing personal reasons, and a minister resigned last week to seek local office, prompting a Cabinet reshuffle.

Months of bad news seem to be reaching a crescendo, as both allies and opponents of the Liberals agree that some policy failures and an inability to seize control of the narrative were dooming Trudeau’s prospects.

Cruel Summer

The summer months were especially brutal for Trudeau. In June, the Liberals lost what was widely regarded as a safe seat in a special election in Toronto; last week, they lost another special election in Montreal.

The shocking loss of seats long controlled by Trudeau’s party drove home the intense levels of voter dissatisfaction.

It’s a terrifying realization for a party that has dominated the Canadian political scene for a decade.

A general election must be held by October 2025 but is likely to come earlier given the precarity of the Liberals’ parliamentary minority. A federal budget that is expected to be voted on next spring could be a trigger if Trudeau cannot rally support to pass it.

Trudeau has tried to bat away the debate over his fate, saying he wants to focus on policy, not politics. But as elections loom, it seems inevitable that he will need to address his unpopularity with voters. His approval rating was near 70% when he swept into power in 2015; today it hovers at 30%.

His fall from public favour tracks similar travails befalling other Western leaders who have been in power through post-pandemic inflation spikes and cost-of-living crises confronting the developed world.

Experts compared Trudeau to President Emmanuel Macron of France, another young liberal who came to power amid palpable optimism a decade ago and now faces crushing discontent at home.

But Macron can’t run for office again because of term limits. Canada doesn’t have limits, and Trudeau seems bent on leading the Liberals to the ballot box again.

Setting aside the specific issues weakening Trudeau and his party, analysts say that making the case for another term — his fourth — would still be a stretch because voters often tire of leaders who stay in power for so long.

“Even if everything was going swimmingly for the Liberals right now, it was always going to be a challenge,” said Shachi Kurl, the president of the Angus Reid Institute, a nonpartisan polling and research firm.

“But things are not going swimmingly,” she added. “Since 2021, it’s as though the Trudeau government has had the reverse Midas touch: Everything they touch is turning to not gold.”

The aversion that many voters feel toward the Liberals does seem to be personal to Trudeau — but Kurl said it was unlikely that the party would turn to a new leader in the next election, partly out of a sense of loyalty.

“Trudeau is the Liberals,” she said, noting that the party feels a collective sense of gratitude for Trudeau for leading it to victory in 2015 after a stretch of poor electoral performances.

Pithy Pierre

At the same time, Trudeau’s chief political opponent, Poilievre, is working to brand himself as the anti-Trudeau: practical and down-to-earth.

One online poll showed that about a third of Canadians wouldn’t be able to name Poilievre from looking at his photo but many would still consider voting for him.

“There is no doubt that Poilievre is the best communicator Trudeau has ever faced,” Butts said.

Poilievre also markets himself as better suited to tackle the country’s problems, said David Coletto, who runs Abacus Data, a Canadian polling and research firm.

“Canadians are not looking for celebrity and flashiness,” he said. “They want somebody who’s going to put out the fire, who’s going to solve the problems.”

For his part, Trudeau has said that Poilievre is simply all talk.

“He will do anything to win, anything to torque up negativity and fear,” he said in April, “and it only emphasizes that he has nothing to say to actually solve the problems that he’s busy amplifying.”

-New York Times

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.