Top Amnesty International official to meet IMF representatives on Sri Lanka deal

By Himal Kotelawala

COLOMBO – Amnesty International Senior Director Deprose Muchena who is in Sri Lanka on an official visit will meet International Monetary Fund (IMF) representatives to discuss a 2.9 billion US dollar deal and its socioeconomic implications.

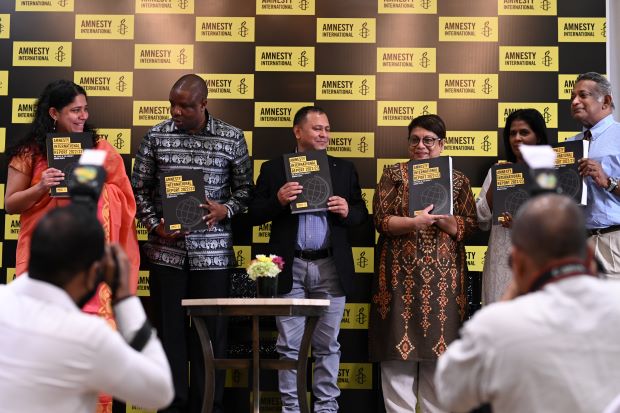

Speaking on the sidelines of Amnesty International’s South Asia regional launch of its State of Human Rights Report for 2022/2023 in Colombo on Tuesday (28), Muchena said he would be meeting IMF officials this week to better understand what is now Sri Lanka’s 17th IMF program.

Specifying that Amnesty International is not seeking a partnership with the IMF, Muchena said his organization wishes to acquaint itself with Sri Lanka’s IMF-backed reform agenda to see if the government’s objectives with regard to macroeconomic reforms align with Amnesty’s own economic, social and cultural rights standards.

The Zimbabwe-born human rights activist also called for transparency and accountability in Sri Lanka’s dealings with the international lender and other agencies.

“Put people at the centre of any economic program that the government is embarking on,” he urged noting that the government does not have a choice between development and human rights, because the pronounced absence of one materially affects the other.

Sri Lanka has to implement a human rights program in parallel to the reforms, said Muchena, calling for a people-first agenda that seeks to protect the public and meet their expectations including the withdrawal of “draconian” measures in response to protests.

Sri Lanka has been on the receiving end of criticism from both local and international human rights groups for its handling of anti-government protests with special focus on its repeated use of the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), a controversial counter-terror legislation whose repeal civil society and political parties, especially those representing ethnic minorities, have called for.

The government, however, has maintained that any arrests of protestors have been of individuals perpetrating violence or otherwise breaking the law. Spokespeople for the government point to a wave of retaliatory mob violence that engulfed the country on May 9, 2022 after pro-government elements launched an unprovoked attack on peaceful protestors. The offices and residences of several parliamentarians were torched and one government MP was killed by a mob that afternoon. The government has blamed ideologically extremist groups for hijacking what was until then a peaceful protest movement and using it to dismantle the state.

Activists and opposition parties, however, contend that the space for dissent is shrinking in Sri Lanka and accuse the government of stifling peaceful protests. Critics of the government point to what they call reckless use of teargas, water cannons and other measures to crack down on peaceful protests.

The mounting criticisms notwithstanding, there has been a notably muted response from the West concerning alleged stifling of protests by the government since President Ranil Wickremesinghe replaced his predecessor Gotabaya Rajapaksa who was forced to resign amid last year’s historic wave of protests.

Some foreign policy analysts believe this is because Wickremesinghe is seen as an ally of Western powers and that any silence on their part may be motivated by strategic interests vis-à-vis Beijing whose influence on Colombo remains considerably high.

Asked to comment on this, Muchena said Amnesty International has been consistent in its communications.

“We have shared our findings in the annual report today. Its primary focus has been to call out double standards,” he pointed out.

The central theme of the report launch event was calling out a purported hypocrisy on the part of the international community.

Muchena highlighted Amnesty’s past pronouncements on vaccine nationalism and other instances of alleged duplicity.

“We have been calling out what we see as double standards [of the] leaders of the world have done on Russian aggression in Ukraine (sic). We have called out selective application of outrage, of the rule of law and of solidarity,” he said, noting that the global community’s silence on creeping authoritarianism and the stifling of protests in countries including Sri Lanka has not gone unnoticed.

“When human rights violations happen in Sri Lanka under this or the previous government, Amnesty International has consistently spoken out against such violations. We have consistently stood on the side of victims of human rights violations and will continue to do so,” he said.

Sri Lanka must ensure that any partnership or deal whether it’s with the IMF, the World Bank or the Asian Development Bank, and consequent macroeconomic policy reform fulfils its obligations to the people.

“Ensure that any partnership, any deal, macroeconomic policy deal, IMF, ADB, implemented in Sri Lanka fulfils accountability to the people, transparency in terms of what’s actually in the content and ensuring that the people and human rights are at the centre of advancing any of the economic reforms that are taking place. That is the Amnesty approach, and we believe that it is consistent in Sri Lanka as it is in Washington DC (sic),” he said.

“But I can’t speak for the broader west, except to call them out when there is a double standard,” he added, noting that any observations Amnesty has made pertaining to the alleged double standards are backed by well-researched evidence.

“We can tell you that the US, the UK and the EU opened their doors to Ukraine refugees but not for Afghanistan, Syria and Yemen refugees,” he said.

Sri Lankan authorities, too, cannot escape their obligations under international human rights law that they have to the people, Muchena pointed out.

“Partners to Sri Lanka should call the government out if they veer off its human rights obligations, in order to avoid double standards,” he said.

Muchena was emphatic that the IMF, particularly with regard to austerity measures, must ensure social protection.

Defenders of the IMF program, however, say a strong social safety net to protect the most vulnerable groups is one of the key pillars of the deal.

“The protection of people in a social way is so key, because we know that IMF programs and World Bank programs have in the past in different countries resulted in austerity. Austerity is about cutting expenditure. It is about reducing the fiscal space of the state to manipulate the budget in such a way that it can allocate resources for social spending,” said Muchena.

“If the government is not going to do that, then it’s going to come stacked against its own people. The IMF and other partners will be held responsible and accountable for outcomes of what they support. We believe that aid must not diminish human rights, but must in fact enhance human rights protection,” he added.

Muchena conceded, however, that he had yet to study the IMF deal, hence the planned meeting with the international lender’s representatives.

Under the latest IMF program, Sri Lanka will be the first country in Asia to undergo a comprehensive governance diagnostic exercise by the global lender. At the request from the authorities, the governance diagnostic will examine the severity of corruption in Sri Lanka and identify key governance weaknesses and corruption vulnerabilities that are macro-economically critical.

Commenting on this, Muchena said: “I have seen elements of tax reform and revenue changes and so on. All those things the government is responsible for doing, we must simplify our role as a human rights movement. At the end of the day, do diagnostics – all these issues that are big English words… austerity, etc – result in advancing human rights or in diminishing human rights?

“Would Sri Lankans have more access to water, food security, and employment opportunities? Is this going to attack the triple burden of unemployment, poverty and inequality?” he asked, adding, “If the answer is no, then it is a bad deal. If the answer is yes, then let’s have reporting mechanisms for the government to account to people.”

He called for transparency of everything that is being discussed between the IMF and the government so that confidence is enhanced in the manner in which economic policy reform is taking place.

Muchena reiterated that human rights have to be prioritized in any macroeconomic reform policy. “Otherwise, it risks antagonising people even further,” he said.

“But our principle, whenever there is economic reform, put human rights first to guarantee protection of ordinary people in a social way. But also avoid austerity, because it is the very problem that <would lead to> protests in the first place.”

-economynext.com

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.