By Shihar Aneez

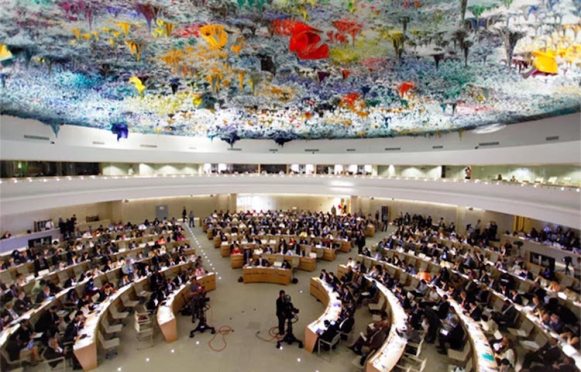

COLOMBO – Sri Lanka is likely to face a tough session of the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) in Geneva as global rights groups and Western nations are increasingly sceptical of the government’s sincerity in implementing certain provisions in the UN resolution passed last year, analysts and diplomats say.

The West and the Tamil diaspora have requested the UNHRC to ensure justice for those subjected to alleged human rights violations in Sri Lanka during and after the government’s 26-year war with Tamil Tiger separatists that ended in 2009.

Rights groups based in Sri Lanka have also sought UN intervention in recent times, as successive governments have failed to stop abuses including the alleged stifling of free expression and suppression of minority rights using a controversial anti-terror law known as the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA).

“[This year’s UNHRC session] is likely to be more severe than last year’s,” said M. A. Sumanthiran, an opposition lawmaker who has been a vocal critic of the government’s human rights record.

“They could also face the issue of land-grabbing in the name of preserving archaeological sites and diverting irrigation to the North this time,” he said.

According the resolution passed at the UN body last year, UN human rights chief Michelle Bachelet received a mandate to collect evidence of crimes allegedly committed during Sri Lanka’s long civil war, which ended with an upsurge of alleged civilian deaths attributed to both the Sri Lankan army and the Tamil Tiger rebels.

Sri Lankan authorities still face questions over thousands of disappeared people, mainly ethnic minority Tamils, people killed in no fire zones, Tamil Tiger rebels who were allegedly killed when they approached with white flags to surrender just before the war was declared ended, and alleged indiscriminate shelling at hospitals in the final phase of the war, among many other allegations.

“The government will claim, as it has repeatedly during the international charm offensive it launched last year, that it is addressing the Human Rights Council’s concerns through its own domestic mechanisms,” said Alan Keenan, International Crisis Group’s (ICG) Senior Consultant on Sri Lanka.

“But this is simply not true. All of its recent initiatives – which are mostly recycled and downsized versions of programs and institutions established by the previous government, which is once denounced – are extremely minimalist,” he said.

120,000 individual pieces of evidence

Bachelet in September last year said the UN body has developed an information and evidence repository with nearly 120,000 individual items already held by the UN and it will initiate as much information-gathering as possible in 2021.

Sri Lanka has vehemently opposed any evidence gathering process and said they have no idea about the 120,000 purported pieces of evidence the UN rights chief has referred to.

Diplomats said Sri Lanka could also face questions over its alleged failure apprehend the perpetrators of the 2019 Easter Sunday bombings. The head of Sri Lanka’s Catholic church Cardinal Malcom Ranjith has sought international backing to secure justice for the relatives of the 269 people killed in the attack.

“Most Christian countries will take up this issue at the UN and Sri Lanka could lose the support of these countries, especially in the Latin American belt,” said a Western diplomat, who did not want to be identified.

Keenan, from the ICG, said the government’s current proposals do nothing to restore the independence of the police and judiciary and oversight commissions which were lost due to a new constitutional amendment that gave sweeping powers to President Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

“The executive’s legal attack on Sri Lanka’s most senior and courageous criminal investigators and the destructive politicization of the investigations into the Easter bombings – these make clear how far the government is from fulfilling its international and domestic, constitutional obligations and put all communities and all political actors at risk,” he said.

“Continued oversight by the High Commissioner and the Human Rights Council is essential in order to prevent the current negative trends from worsening and potentially leading to grave abuses and political instability,” he added.

Bachelet in her report has said she remains concerned about the continued lack of accountability for past alleged human rights violations and recognition of victims’ rights in Sri Lanka, particularly those stemming from the conflict that ended in 2009.

“She highlights continuing trends towards militarization and ethno-religious nationalism that undermine democratic institutions, increase the anxiety of minorities, and impede reconciliation,” the report released by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) last week said.

“At the same time, the High Commissioner recognizes the recent signs of renewed openness of the government in engaging with the OHCHR and the initial steps taken to initiate some reforms.

“The High Commissioner believes, however, that a comprehensive vision for a genuine reconciliation and accountability process is urgently needed, as well as deeper institutional and security sector reforms that will end impunity and prevent the recurrence of violations of the past.”

Most concerns addressed?

The ruling Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP)-led coalition government first rejected all components of the UN resolutions when it took office soon after the election of President Rajapaksa in 2019.

The new government unilaterally withdrew from the resolution to which Sri Lanka was a co-sponsor. That led right groups and Western nations demanding accountability for past abuses to adopt a new resolution that was passed in March last year.

Later, the new government started to follow the same process that was followed by the previous government in addressing human rights concerns as demanded by the UN including amending the PTA.

“If you analyze the facts in the report by the High Commissioner, around 95% of the contents is about the country’s internal political matters,” Foreign Ministry Secretary Jayanath Colombage said at a media briefing on Friday (25).

“There is a Parliament in this country. There is a Cabinet in this country; there is a President; there are citizens in this country. There is a government appointed by the public without any influence.

“It is a government without any dictatorship or militarization, but a democratic government. So the government should have the right to take the decisions needed for the country,” he said.

Colombage said the UN has raised questions over the new constitution which is still in draft stage and has not even been tabled in Parliament.

“If all of these are questioned by Geneva, then there is a problem. We have informed [Bachelet] that she questions the country’s internal affairs and she is not mandated to do so. We have also questioned her as to why she is creating problems for a country which is already a victim of terrorism twice,” Colombage said.

“We are not a country that backed terrorism. We are a country that controlled terrorism. We are a country that gave the right to live to entire [the entire civilian population] of the country.”

He said questions over the war or are related to the war period have greatly reduced in number because “most of the problems have been already addressed”.

“It’s only a few things that are remaining and we as a government are now doing that. We are doing all these not to make the international community happy, but to protect the human rights of our own people.”

Truth and justice for deaths, disappeared?

Many rights activists and some Western nations still see Sri Lanka’s measures including proposed amendments to the anti-terror law, reactivating the work of the Office of Missing Person (OMP) and the Office of National Unity and Reconciliation (ONUR) as attempts to hoodwink the international community.

ICG’s Keenan said though Sri Lanka promised some marginal economic and administrative benefits to a small number of victims and survivors of the war, it resolutely resists any truth or justice – whether with respect to the tens of thousands of unsolved allegedly enforced disappearances or the tens of thousands of others allegedly killed during the war.

“As the High Commissioner’s recent report to the council made clear, none of these marginal programs will make any serious contribution to reconciliation or accountability without being part of a coherent package of transitional justice measures – which the government shows no interest in putting together,” Keenan said.

However, Sri Lanka’s Foreign Minister G. L. Peiris said the country has been endeavouring to strike a just balance between human rights and national security when dealing with terrorism, “as elsewhere in the world”.

“Sri Lanka is convinced that counter-terrorism legislation must secure and protect the rights of persons subject to investigation detention and trial, and must not restrict democratic freedoms such as the freedom of expression.

“With these objectives in view, I recently presented a Bill in the Parliament of Sri Lanka which is an initial step in amending the Prevention of Terrorism Act, 43 years after it was promulgated.”

The Foreign Minister said the evidence gathering mechanism established in the latest resolution is unhelpful to the people of Sri Lanka, will polarize Sri Lankan society, and adversely affect economic development, peace and harmony at a challenging time.

“It is an unproductive drain on Member State resources, at a time of severe financial shortfalls across the entire multilateral system including the High Commissioner’s Office,” he said.

-This article was originally featured on economyenxt.com