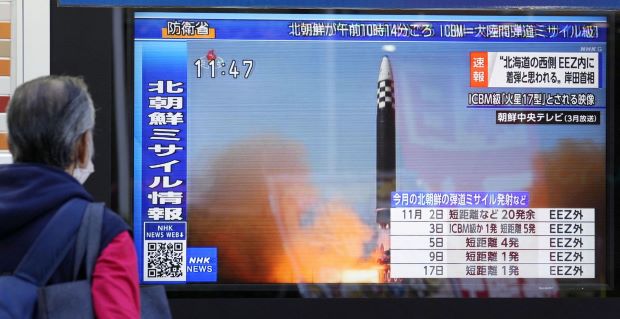

North Korea launches another ICBM, one of its most powerful yet

By Choe Sang Hun and Motoko Rich

SEOUL — North Korea on Friday (18 launched its second intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) this month and one of its most powerful yet, South Korean and Japanese officials said, pressing ahead with its recent barrage of weapons tests in defiance of admonitions from the United States and its allies.

The missile landed in waters west of Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost island. While it was airborne, the commander of the United States Air Force 35th Fighter Wing ordered all personnel at Misawa Air Base in northern Japan to seek cover, a precautionary measure that underscored rising concern in the region over the North’s brinkmanship.

The missile covered a distance of 620 miles and reached an altitude of more than 3,700 miles, according to South Korean and Japanese officials. An ICBM that North Korea fired March 24, apparently its most powerful to date, flew only slightly farther and higher before falling into waters west of Japan, according to the South Korean military’s analysis.

“North Korea is repeating provocations with unprecedented frequency, and this is absolutely unacceptable,” Prime Minister Fumio Kishida of Japan told reporters in Bangkok, where he was attending a regional summit, on Friday. He said the missile had landed within Japan’s exclusive economic zone, and he warned boats in the area to avoid contact with anything that looked like missile parts.

President Yoon Suk Yeol of South Korea called for “strong condemnation and sanctions against North Korea” at the United Nations, his office said.

North Korea has launched at least 88 ballistic and other missiles this year, more than in any previous year, flouting United Nations Security Council resolutions that forbid it from testing ballistic missiles as well as nuclear devices. In recent weeks, the tests have been increasingly provocative.

On Oct. 4, the North fired an intermediate-range ballistic missile over northern Japan, where it triggered air-raid alarms, prompting residents to take cover. On Nov. 2, it launched at least 23 missiles, one of which crossed the two Koreas’ maritime border and fell into international waters off South Korea’s east coast, setting off alarms on a populated island.

The next day, the North tested an ICBM, one of six ballistic missiles that it fired to the east from three locations. The ICBM launch, which set off more alarms in Japan, covered 472 miles while reaching an altitude of 1,193 miles. Firing long-range missiles at a steep angle is seen as a way of demonstrating that the North could hit faraway targets if it chose to do so.

Victor Cha, senior vice president for Asia and head of the Korea division at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, said the recent flurry of tests had been “enabled by China and Russia,” two veto-wielding Security Council members that have scuttled US-led attempts to impose new sanctions on the North.

Cha added that the recent face-to-face meeting between President Joe Biden and Xi Jinping of China “made pretty clear that there was no progress on North Korea. In fact, China almost is sort of decoupling from the North Korea problem and saying ‘It’s all your problem,’ so China’s not going to help.”

The American and South Korean militaries were still analyzing data collected from the Friday launch to determine precisely what type of missile the North had fired this time. It was launched from the Sunan district of Pyongyang, the North Korean capital, South Korean defence officials said.

Japan said the missile appeared to have landed about 130 miles off its shores, and personnel at a United States Air Force base in Japan were ordered to take cover.

North Korea fired a short-range ballistic missile from its east coast Thursday, two hours after its foreign minister, Choe Son-hui, warned that the North’s response would become “fiercer” if the United States, South Korea and Japan stepped up their military cooperation.

The leaders of those three nations met in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, on Monday (14) and vowed to “work together to strengthen deterrence” against the North. They agreed their countries would share warning data in real time to improve their ability to detect and assess the threat posed by incoming North Korean missiles, and Biden reiterated the United States’ commitment to defend its East Asian allies with “the full range of capabilities, including nuclear.”

Adrienne Watson, a spokesperson for the National Security Council in Washington, said after the launch Friday that the United States would “take all necessary measures” to ensure its security and that of South Korea and Japan. “The door has not closed on diplomacy, but Pyongyang must immediately cease its destabilizing actions and instead choose diplomatic engagement,” she said in a statement.

North Korea’s leader, Kim Jong-un, has repeatedly vowed to make the country’s nuclear arsenal and missile fleet bigger and more sophisticated. Analysts say Kim sees that as essential to ensuring his regime’s security, boosting his leverage in any future arms-control talks with Washington and tipping the balance of military power between North and South Korea in the North’s favour.

North Korea first launched ICBMs in 2017, claiming that it could now strike the United States mainland with a nuclear warhead. That year, it also conducted its most recent nuclear test, its sixth.

Soon afterward, Kim announced a halt to all nuclear and long-range ballistic missile tests, part of the diplomatic push that led to his series of summit meetings with then-President Donald Trump. Those talks collapsed with no agreement on rolling back the North’s weapons program or lifting the UN sanctions imposed in response to it, and this year, North Korea ended its self-imposed ICBM test moratorium.

Between February and May, North Korea conducted six missile tests that appeared to involve ICBMs, including a Hwasong-17, its newest and biggest long-range missile. The Hwasong-17 has had a chequered testing history since it was first displayed at a military parade in October 2020. In March, one of them exploded shortly after take-off, according to South Korean officials.

After its powerful ICBM test in March, North Korea said that missile had been a Hwasong-17. But South Korean officials later said it had actually been an older model, a Hwasong-15, accusing the North of exaggerating its weapons development progress by falsely claiming a successful Hwasong-17 launch.

The missile launched Nov. 3 did appear to be a Hwasong-17, the officials said. Though they believe the test ended in failure, they also said it indicated that the North was making some progress with the two-stage missile. Unlike the one that exploded in March, the Hwasong-17 launched in November successfully separated its second, warhead stage, they said.

In the current geopolitical context, with Russia’s war in Ukraine raging and US-China relations at a low, North Korea most likely sees opportunities to develop its weapons and provoke its enemies with virtual impunity, analysts say. The United States and its allies have warned for months that the emboldened North could resume nuclear tests at any time.

“While China and Russia are shielding North Korea from UN sanctions, Pyongyang is taking the opportunity to technologically develop a long-range missile that has failed in previous tests,” said Leif-Eric Easley, a professor of international studies at Ewha Womans University in Seoul. “Regardless of actions taken by the U.S. and its allies, the Kim regime appears to be deliberately ratcheting up its provocations toward a major nuclear test.”

Cha said it was difficult to see a viable solution at the moment, given that North Korea had not responded to diplomatic outreach from the Biden administration. “The only thing that gets us out of this spiral is diplomacy, and North Korea is not really interested in it right now,” he said.

-New York Times

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.