A brother lost, justice denied

Nimalarajan’s sister hopes President AKD will help bring closure for her family

By Saroj Pathirana

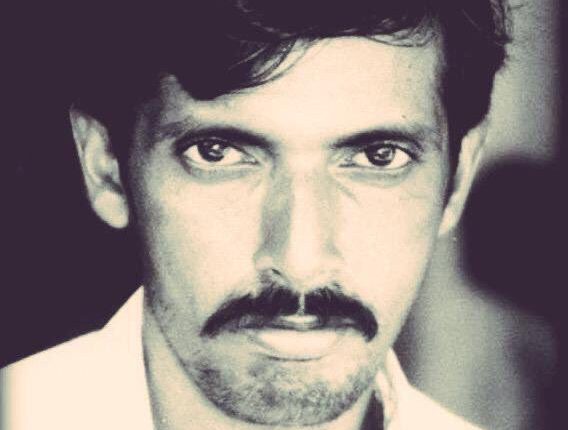

In Sri Lanka, where decades of ethnic conflict have left deep scars, some journalists dared to tell the stories others feared to voice. Nimalarajan Mylvaganam, considered to be one of the few independent voices from the war-torn Jaffna peninsula at the height of the conflict, was one of them. He reported for various news organizations, including the BBC Sinhala (Sandeshaya) and Tamil (Tamilosai) services, Ravaya Sinhala weekly and Virakesari Tamil newspaper. In addition to the atrocities during the ongoing conflict, he also covered many other sensitive issues such as paramilitary activities and election violence.

But this bravery came at a cost. On October 19, 2000, gunmen silenced his independent reporting with bullets, leaving his family and the journalism community grappling with questions of justice and accountability.

His assassination underscored the perilous climate for press freedom during the civil war. Today, nearly 25 years later, his sister Nimalarani Mylvaganam clings to hope that a new government will finally act to break the cycle of impunity for crimes against journalists.

Sister’s ‘second father’

Growing up in Colombo in the early 1970s, Nimalarani loved sitting on her brother’s lap. Morning, afternoon, or evening, it was her favourite seat – one she treasured until she left Sri Lanka decades later. Her brother would hold her close, telling her stories as she perched there.

“He was not just my brother but my second father,” she says, her voice trembling with emotion.

In 1995, Nimalarani migrated to Canada, got married, and settled there. She still has fond memories of her visit to Sri Lanka in 1999, when her ‘second father’ met her husband and the children for the first time.

“He was so happy to see my kids,” she recalls wistfully. Her three-year-old son still recalls how his uncle, or mama, drove him around Jaffna on his motorcycle for hours.

“That was the last time I saw him. I never thought it’d be the final time.”

A year later, her brother was brutally murdered. Gunmen burst into his house in Jaffna and shot him five times. They attacked his father with a knife and hurled a grenade, injuring his mother and nephew.

The nephew, Prasanna – now living in Canada – remembers vividly how, just the day before, his uncle had taken him on a motorbike ride to find a pair of shoes. Less than 24 hours later, Nimalarajan was gone, and Prasanna was left badly injured. The attack occurred during curfew hours in Jaffna’s high-security zone, close to several military checkpoints.

At the time of his killing, Sri Lanka was engulfed in intense conflict and repression. The civil war between the government and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) had created a highly militarized and polarized environment, particularly in Jaffna. The political climate was volatile, marked by heightened ethnic tensions, election-related violence, and suppression of dissent. Journalists faced severe threats from all sides, including the military, paramilitary groups, and the LTTE, for exposing abuses. The 2000 general election, held amidst this tense backdrop, was marred by violence and allegations of rigging. Nimalarajan’s fearless journalism highlighted these issues, making him a threat to powerful factions, ultimately leading to his assassination. He was 39.

He left behind his wife and three daughters, all under the age of five.

“He was such a kind person. Everyone loved him,” Nimalarani recalls. “He cared so deeply about our family and others. That’s why people in Jaffna, Kilinochchi, and beyond still commemorate him every year on his death anniversary.”

Born in Colombo as the second of five children, Nimalarajan grew up with his elder sister Premarani and younger sisters Kamalarani, Selvarani, and Nimalarani. The family lived in Colombo until the 1983 riots, widely known as ‘Black July’.

The Mylvaganam family was living in Wattala when violent anti-Tamil pogroms erupted after the Tamil Tigers killed 13 Sri Lankan soldiers in an ambush. Sinhala mobs, often with government complicity, attacked Tamil homes, businesses, and individuals across the country, particularly in Colombo. Thousands of Tamils were killed, properties were destroyed, and many were displaced. The violence marked a turning point, intensifying ethnic divisions and fuelling the Tamil separatist movement.

“Some people came to kill us but our neighbours – who were Sinhalese – protected us. They kept us in a safe house nearby and brought food for us. In fact, all the neighbours guarded us. We stayed in that safe house for about a month,” recalls Nimalarani.

“But we couldn’t hide all the time, so my parents decided to move to Jaffna.”

That was their second move due to racial tensions. In 1979, they were forced to move from Rajagiriya to Wattala.

Following Nimalarajan’s murder, and the attack on his parents and nephew, the family was on the move again. This time, his wife, children, parents and nephew Prasanna moved to Canada. Today no member of his extended family lives in Jaffna, as former BBC journalist Frances Harrison tweeted in 2023. (https://x.com/francesharris0n/status/1676151905767108608)

Refused to be silenced

Six suspects were arrested. But after a lengthy legal process, the Jaffna Magistrate’s Court ordered their release in May 2021, following the advice from the Attorney General’s Department.

Two of the six suspects are currently overseas.

A paramilitary group turned political party, the Eelam People’s Democratic Party (EPDP) is accused of orchestrating the murder in retaliation for his reporting, though the party denies the allegations.

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) said at the time of the murder: “Local journalists suspect that Nimalarajan’s reporting on vote-rigging and intimidation in Jaffna during the recent parliamentary elections may have led to his murder.”

As Nimalarani recalls, her brother had received several threats before the murder. “He said he had a lot of warnings. One day my mother picked up the phone, and she was told that ‘your son is going to die soon’.”

The family has urged him to join his sisters in Canada. Under pressure from the parents and the sisters, Nimalarajan has promised to leave Sri Lanka but was in no mood to give up his journalism. His last despatch to the BBC reported about the election malpractices during the general election, especially in the EPDP strongholds. Most of the suspects arrested were EPDP cadres, but none admitted to the murder. Despite these arrests and accusations, the EPDP denied any involvement, dismissing them as politically motivated.

“Everybody knows who killed him but there is no proof – nobody saw the attackers,” says Nimalarani. “It was dark when they came. Our family only heard what happened.”

Nimalarajan’s mother Lily Theres Mylvaganam and father Sangarapillai Mylvaganam have passed away without seeing justice for their son’s murder.

In 2010, his father, Sangarapillai Mylvaganam, told the BBC Sinhala service from Canada: “The people responsible for his murder are in the government. As a result, nothing has been done to find the killers.”

“I would like people to remember him as a courageous journalist who served his community,” Mylvaganam told Reporters Without Borders in 2010.

Decades of impunity

Meanwhile, in February 2022, the War Crimes Team of the British Metropolitan Police arrested a 48-year-old man in Britain over Nimalarajan’s murder. The suspect was later released. However, according to the Metropolitan Police, so far no one has been charged in the UK for the murder of Nimalarajan.

Adam French, a spokesman for the British Metropolitan Police told Free Media Movement: “In terms of the person who was previously arrested, I can confirm that they have not been charged at this stage, but they remain under investigation and our enquiries continue in respect of this investigation.”

In a statement issued on June 4, 2024, the Metropolitan Police appealed for more information on the murder, stating: “Counter Terrorism detectives investigating allegations of war crimes linked to the Sri Lankan civil war in the early 2000s are appealing for anyone who might have information that could assist their investigation to contact police.”

Commander Dominic Murphy said the need for “as much eye-witness testimony as possible” to build the case leading to prosecution.

They questioned whether the suspect would be extradited to Sri Lanka if the Sri Lankan government made such a request, Metropolitan Police’ Adam French said: “In terms of extraditing any individuals from the UK to a foreign country, that would be something that the UK’s Home Office would consider should any such requests be made by a foreign country, so it would be a question for the Home Office, although I believe that they tend not to discuss specific individuals or cases.”

For nearly 25 years, justice has been elusive for the murder of the ‘voice of Jaffna.’ However, the new National People’s Power government, led by President Anura Kumara Dissanayake, has vowed to expedite investigations into crimes against journalists from past regimes.

It is not clear whether any previous government has made a request to extradite the suspect arrested in the UK. The Cabinet spokesman, Health and Media Minister Dr Nalinda Jayatissa told Free Media Movement that he’d check the latest status of the murder inquiry before commenting about a request for the extradition of suspects.

Hope for justice

The New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) has urged the new government to reopen the inquiries on attacks on journalists over the years.

“Justice has remained elusive for the fatal shooting of Sri Lankan journalist Mylvaganam Nimalarajan for 24 years too long,” said Beh Lih Yi, CPJ’s Asia program coordinator. “We call on the newly elected government of Sri Lanka to oversee a fresh and impartial investigation into Nimalarajan’s murder, as well as dozens of other gruesome attacks on journalists during and in the aftermath of the country’s 26-year civil war that ended in 2009. No stone should be left unturned in pursuing accountability for all perpetrators,” Lih Yi urged.

Nimalarani agrees. “Not only my brother, but a lot of people also never got justice. Many people have lost brothers, sons, fathers, daughters … I hope they all will get justice.”

She is in no mood, however, to keep talking about her brother’s murder. “When I talk about it, I get stressed. I can’t forget it, but I don’t want to keep talking about it. It is very hard.”

But she adds after a pause, “They didn’t just kill my brother”.

Her voice is soft but resolute.

“They killed my second father. Now, I feel like nobody is here for me anymore.”

As many in the North and East have bestowed faith on the new president, Nimalarani is also hopeful that President Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s resolve to bring justice for serious crimes committed over the years, despite decades of waiting, would prevail and would signal a pivotal transformation in the nation’s approach to accountability and reconciliation.

“I hear the President is making positive changes. I hope he will find justice for my brother.” Her voice carries a calm determination. “It’s been nearly 25 years since I lost him. Only God can decide, but I’d be happy if justice finally comes.”

-Saroj Pathirana is a Pulitzer Ocean Reporting Network (ORN) Fellow and a veteran journalist with over 25 years at the BBC World Service’s Sinhala service, where he served as a producer, reporter, and editor. Now a freelance journalist, he reports on Sri Lanka for international outlets, including BBC and Al Jazeera, and is the Editor of Midpoint.lk’s English edition. Passionate about mentoring young journalists, he also runs Sandeshaya by Saroj, a public-service current affairs YouTube channel. This article is part of a 10-piece series on impunity for crimes against journalists, published by the Free Media Movement to mark Black January 2025

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.