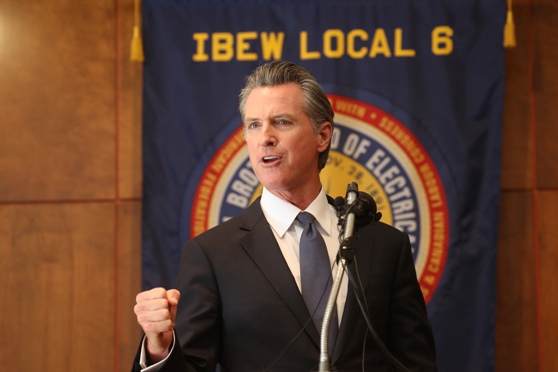

Newsom survives California recall vote and will remain Governor

By Shawn Hubler

SACRAMENTO — A Republican-led bid to recall Gov. Gavin Newsom of California ended in defeat late Tuesday (14), as Democrats in the nation’s most populous state closed ranks against a small grassroots movement that accelerated with the spread of COVID-19.

Voters affirmed their support for Newsom, whose lead grew insurmountable as the count continued in Los Angeles County and other large Democratic strongholds after the polls had closed. Larry Elder, a conservative talk radio host, led 46 challengers hoping to become the next governor.

The vote also spoke to the power liberal voters wield in California: No Republican has held statewide office in more than a decade.

But it also reflected the state’s recent progress against the coronavirus pandemic, which has claimed more than 67,000 lives in California. The state has one of the nation’s highest vaccination rates and one of its lowest rates of new virus cases — which the governor tirelessly argued to voters were the results of his vaccine and mask requirements.

Although Newsom’s critics had started the recall because they opposed his stances on the death penalty and immigration, it was the politicization of the pandemic that propelled it onto the ballot as Californians became impatient with shutdowns of businesses and classrooms. In polls, Californians said no issue was more pressing than the virus.

“As a health care worker, it was important to me to have a governor who follows science,” said Marc Martino, 26, who was dressed in blue scrubs as he dropped off his ballot in Irvine.

The Associated Press called the race for Newsom, who had won in a landslide in 2018, less than an hour after the polls closed Tuesday. About 66% of the eight million ballots counted by 9:30 p.m. Pacific Time said the governor should stay in office.

“It appears that we are enjoying an overwhelmingly ‘no’ vote tonight here in the state of California, but ‘no’ is not the only thing that was expressed tonight,” Newsom told reporters late Tuesday.

“We said yes to science. We said yes to vaccines. We said yes to ending this pandemic. We said yes to people’s right to vote without fear of fake fraud and voter suppression. We said yes to women’s fundamental constitutional right to decide for herself what she does with her body, her faith, her future. We said yes to diversity.”

Considered a bellwether for the 2022 midterm elections, the recall outcome came as a relief to Democrats nationally. Though polls showed that the recall was consistently opposed by some 60% of Californians, surveys over the summer suggested that likely voters were unenthusiastic about Newsom. As the election deadline approached, however, his base mobilized.

President Joe Biden, Vice President Kamala Harris and Sens. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota travelled to California to campaign for Newsom, while Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont and former President Barack Obama appeared in his commercials. Some $70 million in contributions to his campaign poured in from Democratic donors, tribal and business groups and organized labour.

The governor charged that far-right extremists and supporters of former President Donald Trump were attempting a hostile takeover in a state where they could never hope to attain majority support in a regular election. He also contrasted California’s low rates of coronavirus infection with the large numbers of deaths and hospitalizations in Republican-run states like Florida and Texas.

Electoral math did the rest: Democrats outnumber Republicans 2-1 in California, and pandemic voting rules encouraged high turnout, allowing ballots to be mailed to each of the state’s 22 million registered, active voters with prepaid postage.

Initiated by a retired Republican sheriff’s sergeant in Northern California, Orrin Heatlie, the recall was one of six conservative-led petitions that began circulating within months of Newsom’s inauguration.

Recall attempts are common in California, where direct democracy has long been part of the political culture. But only one other attempt against a governor has qualified for the ballot — in 2003, when Californians recalled Gov. Gray Davis on the heels of the Sept. 11 attacks, the dot-com bust and rolling electricity blackouts. They elected Arnold Schwarzenegger to replace Davis as governor, substituting a centrist Republican for a centrist Democrat.

Initially, Heatlie’s petition had difficulty gaining traction. But it gathered steam as the pandemic swept California and Newsom struggled to contain it. Californians who at first were supportive of the governor’s health orders wearied of shutdowns in businesses and classrooms, and public dissatisfaction boiled over in November when Newsom was spotted mask-free at the French Laundry, an exclusive wine country restaurant, after urging the public to avoid gatherings.

A court order extending the deadline for signature gathering because of pandemic shutdowns allowed recall proponents to capitalize on the outrage and unease.

As the outcome in Tuesday’s recall election became apparent, Darry Sragow, a Democratic strategist and publisher of California Target Book, a nonpartisan political almanac, said the governor held off “a Republican mugging” and “could come out of this stronger than ever, depending on his margin.”

Recall backers also claimed a measure of victory.

“We were David against Goliath — we were the Alamo,” said Mike Netter, one of a handful of Tea Party Republican activists whose anger at Newsom’s opposition to the death penalty, his embrace of workers in the country illegally and his deep establishment roots helped inspire the attempted ouster.

Just gathering the nearly 1.5 million signatures necessary to trigger the special election was “a historic accomplishment,” Heatlie said.

The recall campaign, the two men said, had expanded the small cadre that began the effort into a state-wide coalition of 400,000 members who are already helping to push ballot proposals to fund school vouchers, forbid vaccine mandates in schools, and abolish public employee unions, which have been a long-standing Democratic force in California.

Other Republicans, however, called the recall a grave political miscalculation. About a quarter of the state’s registered voters are Republicans, and their numbers have been dwindling since the 1990s, a trend that recall proponents believed might be reversed if they could somehow flip the nation’s biggest state.

Tuesday’s defeat instead marked “another nail in the coffin,” said Mike Madrid, a California Republican strategist who has been deeply critical of the party under Trump, charging in particular that the GOP has driven away Latino voters.

Some Democratic observers were circumspect, warning that the disruption caused by the recall effort hinted at deeper problems.

“This recall was a canary in the coal mine,” said Sragow, a veteran Democratic strategist who cited the state’s income disparities, housing shortages and climate crises. “And until the issues that created it get dealt with, people in power are in trouble. There’s a lot of anger and fear and frustration out there.”

-New York Times