50 years after Vietnam, thousands flee another lost American war

By Miriam Jordan

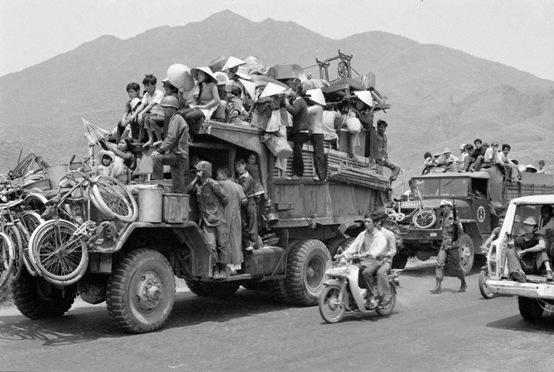

It was the end of a decades-long American military engagement overseas, and thousands of US allies were clamouring to board the last planes leaving for, they hoped, eventual resettlement in the United States. Their capital had fallen. Deadly reprisals for those who stayed behind were almost certain.

It was 1975, the tumultuous backdrop was Southeast Asia, and Washington largely opened America’s doors, letting in some 300,000 refugees from Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia over the next four years. Joe Biden, then a young US senator from Delaware, co-sponsored landmark legislation that won unanimous passage in the Senate and was signed into law in 1980, divorcing refugee admissions from US foreign policy and generally expanding the number allowed into the country each year.

Now, as similar scenes of chaos and desperation unfold in Kabul with the conclusion of America’s 20-year war in Afghanistan, most analysts say there is little chance the country will repeat the extensive refugee-resettlement effort that accompanied the end of the war in Vietnam.

Decades of lukewarm public sentiment over refugees, a toxic political stalemate over immigration and contemporary concerns over terrorism and the coronavirus pandemic have all but eliminated the possibility of a similar mass mobilization.

Since the 1930s, polling by Gallup has shown time and again that Americans are ambivalent toward accepting refugees. As recently as 2018, amid a surge of Syrians, Iraqis and Afghans seeking safe haven, Americans said they would rather accept ordinary immigrants coming to look for better lives than refugees fleeing war and violence, according to the Pew Research Centre — the opposite of respondents in 16 other Western countries.

The refugee law that Biden co-sponsored calls for the president to determine the number of refugee admissions for a given year based on humanitarian concerns or what is otherwise in the national interest, giving the White House wide latitude.

When the program began in 1980, the US capped the number of refugees at 234,000. But that limit has trended generally downward since, hitting what many thought would be a low of 15,000 in the last year of the presidency of Donald Trump, whose hostility to all kinds of immigration was a cornerstone of his administration.

Biden ran on a pledge to adopt a more humane policy and rebuild the resettlement program, but the country is poised to admit the lowest number of refugees in the history of the program — there have been 6,246 through July 31 — partly because the pandemic closed consulates and delayed processing of applications.

The crisis conditions in Afghanistan have prompted urgent calls to resettle Afghans who are trying urgently to leave before a Taliban crackdown, starting with the translators and others who face retribution because of their work with the US military.

“President Biden has said, ‘America is back’ — is the city on the hill. Now he has the chance to prove it,” said Ryan Crocker, whose long diplomatic career included stints as US ambassador to both Iraq and Afghanistan.

More than a dozen governors from both parties have expressed a willingness to receive refugees, and faith-based groups across the country are volunteering to help sponsor Afghan families. Utah Gov. Spencer Cox, a Republican, said the state had “a long history of welcoming refugees from around the world” and was “eager to continue that practice” with Afghan refugees.

But with large numbers of people fleeing violence and poverty in Central America and other countries pushing recently across the border with Mexico, some conservatives are calling for a hard line against large numbers of Afghan refugees.

Between 1945 and 1950, the United States admitted about 350,000 Europeans, mainly Jews who survived the Holocaust.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower paroled some 40,000 Hungarians into the United States, and President John F. Kennedy went on to allow several hundred thousand Cubans opposed to the regime of Fidel Castro. Then came Vietnam and the exodus of hundreds of thousands of boat people after the fall of Saigon.

In all of those cases, refugees were casualties of America’s Cold War campaign against communism, and they enjoyed a certain amount of public support.

“During the ’80s, refugees are relatively popular because they are seen as a symbol of the superiority of our political and economic system,” said Serena Parekh, author of two books on refugees, including ‘No Refuge: Ethics and the Global Refugee Crisis’, published last year. “They are part of Cold War politics and play well into national interests.”

In the late 1980s, the United States received tens of thousands of Soviet Jews and other religious minorities for whom the American public had sympathy. In the 1990s, there was an influx from the conflict in the former Yugoslavia.

But by the late 1990s, the Congressional Black Caucus was criticizing the program for not assisting enough Africans fleeing bloodshed in countries such as Somalia, forcing them to remain parked in teeming camps. Public attitudes toward refugees already were shifting, said Parekh, a professor at Northeastern University.

“Refugees start to look more foreign or dissimilar to people in the US,” she said. “Instead of being seen as people courageously fleeing persecution, they are seen as people who will be an economic burden.”

In response to 9/11, the United States invaded Afghanistan; two years later, it invaded Iraq.

Back home, public concern grew when immigrants — not refugees — were involved in a handful of other deadly terror attacks. The administrations of George W. Bush and Barack Obama added layers of security checks to the application process.

“The refugee program became so mired in red tape and extreme vetting that it looks like a program designed to keep people out of the United States rather than rescue them,” said Mark Hetfield, CEO of HIAS, a resettlement agency founded as Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, and who has worked in the field for 32 years.

After terrorist attacks in Paris in 2015, more than 20 governors announced that their states would not accept refugees from Syria, fearing terrorist infiltrators.

Not long after taking office, Trump slashed the refugee cap to 50,000 from the 110,000 set by Obama, and issued an executive order barring the entry of people from several predominantly Muslim countries. The next year, he set a ceiling of 45,000; fewer than half arrived amid tighter background checks and restrictions.

Biden quickly began to undo his predecessor’s immigration policies, but rising public concern over the rapid increase in unauthorized crossings on the southwestern border prompted him to defer a plan to increase the cap on refugees this year.

The delay forced 700 refugees, already screened and holding tickets, to be pulled off flights. There was swift rebuke from human rights activists and fellow Democrats, and within hours, the White House announced that the 2021 cap would be raised to 62,500. But it was not clear whether — given the pandemic, the program’s depletion by his predecessor and soaring numbers at the border — this number would be achieved.

As of March 31, the latest data available, 20,829 Afghans, plus 52,799 family members, had received special immigrant visas since 2014 under a separate program created by Congress for those who could face reprisals for their work with US troops.

One of the Afghans who was evacuated and arrived in Houston this month, a 32-year-old interpreter who worked with a US Marines platoon, said he managed to escape only days before his city, Gardez, south of Kabul, fell to the Taliban.

“I am just worried for so many people still there,” said the man, who wanted to be identified only by his English nickname, Harry, out of fear for the relatives he left behind. “They are hiding, or moving their families from place to place.”

Biden on Wednesday (18) said the United States hoped to evacuate between 50,000 and 65,000 Afghan allies, including their families, and had approved an additional $500 million to help with “urgent refugee and migration needs.”

Many of them will be directed to other countries for processing. How many Afghans will eventually be welcomed into the United States remains an open question, one that Crocker, the former diplomat, said is key to everything the United States tried to achieve during the war.

“We owe it to Afghan females, the free media,” he said. “It’s for all those people we basically said to, ‘You go ahead and build a new, free open society and we will be here to see you get that done and that you get it done safely.’

“We have the moral obligation and the capacity to do it.”

-New York Times