Middle East pivot to Asia is strategic this time

By Una Galani

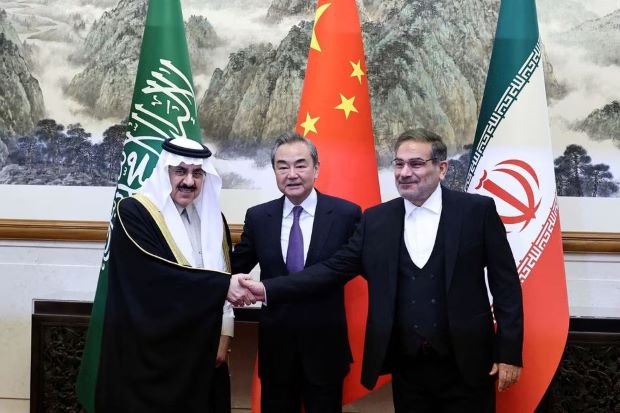

SINGAPORE – For a sign of the new business times, look no further than China’s success in brokering a pledge between Saudi Arabia and Iran to restore diplomatic ties. It’s a huge political win for Beijing. For bankers, it’s another sign that their next big opportunity stems from a deeper Asia-Middle East embrace.

Xi Jinping has brokered a deal the United States would have found hard to secure, despite its traditional military influence in the Middle East. China’s president did so on the same day he officially secured a third term, and in the same week the People’s Republic paved the way for a $2.9 billion International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailout for Sri Lanka by committing to reorganize the island’s debt. Both developments are constructive for global stability and suggest China can be a responsible big power.

The Middle East has trained its financial sights on Asia before. In 2014 the Qatar Investment Authority said it would invest up to $20 billion in Asia within five years. That failed to flourish much further as a scandal at Malaysia’s sovereign fund, 1MDB, was linked back to its peers and financial institutions in the Gulf.

This time, the interest appears more mutual and more strategic. Following the West’s schism with Russia over Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine, some policymakers think the world is splitting into two blocks, with the United States and Europe on one side, and a China-led Asia and Russia on the other. The reality is more complicated, but Asia’s growing hunger for energy means it has an incentive to get closer in more ways to Gulf petrodollar economies which have traditionally looked west for security, a place to sell their oil and gas, and to park their money.

It feels like a story whose time has come, said one Middle East-based bank boss. Oil demand equivalent in the Americas and Europe is set to fall by 7.6 million barrels per day by 2045, according to the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). By contrast India and China alone could require an extra 8.5 million barrels per day. The duo will account for around 70% of total demand growth over the period, OPEC reckons.

At current rates of growth, emerging Asia will become the top trade partner for the Gulf countries by 2028, per Asia House, surpassing advanced economies. Those dynamics are yielding new landmarks: QatarEnergy, for example, signed a record 27-year deal in November to supply liquefied natural gas to China’s Sinopec. Whether Beijing’s peace deal lasts or not, financiers are betting the uptick in energy trade will spill over into their industry.

Middle East sovereign funds have started popping up more frequently as key investors in strategically important Asian share placements, including Indonesia’s GoTo. Life Insurance Corporation of India and Gautam Adani’s since-aborted capital call at Adani Enterprises. His Indian empire has attracted billions of dollars, too, from Abu Dhabi’s enigmatic $235 billion International Holding Company; both are publicly traded entities whose businesses reflect national strategic priorities including energy and food.

Elsewhere, an official Hong Kong visit led by the city’s leader John Lee to Riyadh this year ended with the bourses of Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing and the Saudi Tadawul Group signing cooperation agreements. As US-China relations continue to sour, the Asian financial centre is looking to the Middle East to find new foreign companies to trade in the territory. It’s not a stretch to imagine Gulf groups like Saudi Aramco doing so, given Beijing intends to let Chinese investors buy shares, via the bilateral Stock Connect programme, of foreign companies listed in the hub.

Meanwhile, a plan unveiled in January for a dual listing of Olam’s agriculture unit in Singapore and Saudi Arabia, where food security is a key issue, would have been unthinkable a few years ago. Ditto First Abu Dhabi Bank’s takeover interest in Standard Chartered, an emerging market-focused bank.

The Gulf petro-kingdoms, whose economies are collectively worth $2 trillion, also look more attractive as a market and place to set up factories. Saudi Arabia under Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and United Arab Emirates under President Mohammed bin Zayed al-Nahyan are competing to drive economic development. With Saudi’s NEOM flagship mega-project set to be a major producer of green hydrogen and China already a green technology leader, there’s a case for Beijing to locate factories manufacturing related panels and other clean-tech equipment in the region, as well as exporting more there.

The Saudi-Iran deal will in the short term reduce the threat of regional conflict. That local harmony may not last. But China’s role in cementing it will grease the wheels of the next big global trade.

Context News

Saudi Arabia and Iran agreed to restore diplomatic relations after bilateral talks in China were successful, the three countries said in a surprise joint statement released on March 10.

Delegations from the two Middle East countries held talks in Beijing between March 6 and 10, the statement added. Those talks were not previously disclosed.

Saudi Arabia cut ties with Iran in 2016 after its embassy in Tehran was stormed during a dispute between the two countries over Riyadh’s execution of a Shi’ite Muslim cleric.

-Reuters

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.