By P. K. Balachandran

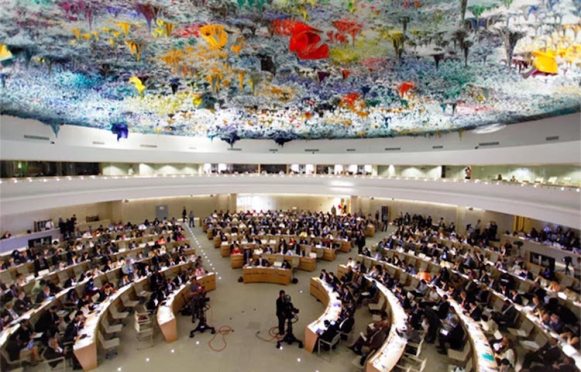

COLOMBO – The UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) was set up in 2006 with the lofty and challenging aim of protecting human rights across the globe, irrespective of the differences in the political and socio-economic condition of the countries. While it has chalked up notable achievements in the past 15 years, the UNHRC has been struggling to fulfil its mandate, being pulled in various directions by multiple and competing national and geo-political interests.

In 2007 the UNHRC adopted an ‘Institution-building package’ to guide its work and set up procedures and mechanisms. Among these were: the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) mechanism which assesses the human rights situation in all UN Member States; the Advisory Committee which serves as the Council’s ‘think tank’; and the Complaint Procedure which allows individuals and organizations to bring human rights violations to the attention of the Council.

The UNHRC works with the UN Special Procedures which are made up of Special Rapporteurs, Special Representatives, Independent Experts and Working Groups that monitor, examine, advice and publicly report on thematic issues or human rights situations in specific countries. The Council’s work and functioning are reviewed every five years by the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA).

The Council consists of 47 Member States, which are elected directly and individually by secret ballot by the majority of the members of the UNGA. Membership is based on equitable geographical distribution. The seats are distributed as follows: Group of African States, 13; Group of Asian States, 13; Group of Eastern European States, 06; Group of Latin American and Caribbean States, 08; and Group of Western European and other States, 07.

Members of the Council serve for a period of three years and will not be eligible for immediate re-election after two consecutive terms; Membership is open to all countries in the UN. However, when electing members, the UNGA is expected to take into account the contribution of candidates to the promotion and protection of human rights and their voluntary pledges and commitments made thereto. By a two-thirds majority of the members present and voting, the UNGA may suspend the rights of membership in the UNHRC of a member of the Council that commits gross and systematic violations of human rights.

Conflicting Expectations

The member States of the UN have been having conflicting expectations from the UNHRC. Powerful Western nations, independence and sovereignty-valuing developing nations and victims of rights abuses, all have had their grievances about the Council’s performance. But all of them also agree that the UNHRC is useful because it is the only forum where a country or a persecuted people, can take their grievances to.

The US, which left the body in a huff, has now come back realizing that it cannot be a world power by opting out of world institutions, and that the UNHRC is as good as any to demonstrate its clout.

The issues facing the UNHRC were highlighted in a review by the General Assembly in November 2019. On the plus side, in the review period, the UNHRC had adopted 88 resolutions, 42 UPR decisions and two presidential statements. All 193 UN Member States were reviewed twice under the UPR. The Trust Fund had enabled the participation of 32 countries; including 11 small island developing States with no permanent representation in Geneva.

The then UNHRC President, Coly Seck (Senegal) said the body had remained faithful to the mandate entrusted to it by the UNGA “to promote universal respect and the defence of all human rights and fundamental freedoms for all without distinction and in a fair and equitable manner”. The Council’s work included technical assistance and capacity building, particularly in Cambodia and Georgia. The then General Assembly President, Tijjani Muhammad‑Bande (Nigeria), said the UNHRC’s agenda included vital developmental issues such as education, inclusion, poverty eradication and climate action which plague developing countries.

The UNHRC provided the UNGA with a range of recommendations, as in regard to Syria and the Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar. The UNHRC also highlighted reprisals against and intimidation of human rights activists in several countries. The Ukrainian delegate said Sudan’s transformation into a democratic nation could be deemed as a success story. He appreciated the UNHRC’s concern over the invasion of the Crimea, and other rights abuses by Russia.

Conflicting Issues

However, several countries slammed the UNHRC for the way its membership is constituted and its selectivity in condemning human rights violations. The US has been opposed to throwing open membership to countries which are known violators of rights (like China), pointing out that one of the essential criteria for election to the UNHRC is a demonstrated commitment to human rights. But others argue that membership will be a sobering influence on rights violating countries. The US was also miffed with the regular targeting of its protégé, Israel, and left the UNHRC.

Sri Lanka is of the view that the UNHRC has been turned into an arena of international power competition and that the country is being targeted by the West, deeming it to be a proxy of China, the West’s principal rival. This was stated obliquely by the Sri Lankan Foreign Minister Dinesh Gunawardena in the on-going 46th Session of the Council. Venezuela has also felt victimized by the US. Bangladesh regrets that neither the Special Rapporteur on the human rights situation in Myanmar nor the UN Independent International Fact‑Finding Mission have been able to get access to that country. Lebanon and Israel have been defying the UN with impunity as they have the backing of a big power.

The European Union has been wanting a stronger emphasis on the importance of respecting international law when applying counter‑terrorism measures. The latest draft UNHRC resolution against Sri Lanka has sought a data collecting mechanism. These data could be a basis for legal action against Sri Lanka by Members States. Sri Lanka is opposed to this mechanism as it could lead to action by any member State using universal jurisdiction.

The Cuban Vice Minister for Foreign Affairs complained that while “bitter criticism” continues to be levelled at the Global South, there is silence when the same violations are committed in developed countries. Further, the issue of human rights should not be “securitized” he said. In other words, the UNHRC must not be linked to the Security Council as that would be tantamount to coercion which will be counterproductive. Referring to the economic blockade imposed by the US on Cuba, the delegate called it a “systematic violation of the human rights of the people of Cuba”.

The Iranian delegate that the UNHRC’s link with the Security Council is an open invitation for a further politicization of human rights. Belarus said that the UNHRC exceeds its role by getting involved in “political floggings” and is therefore losing trust and credibility. The Council, supposedly fighting against repression, is itself turning into a repressive body, motivated by narrow political interests of certain Member States, it charged. The UNHRC is obsessed with political topics to the exclusion of Sustainable Development Goals.

The Russian delegate said the time has come to give some thought to whether the work of the UNHRC helps improve the human rights situation in individual countries. “The answer is no,” he said emphatically. “In the hands of unethical actors, the Council is quickly frittering away the impartiality of its work. It is openly being used by certain States to advance their political goals. Its agenda is full of topics that are detached from human rights and has little to do social and economic development,” he said.

The representative of China said the statement made by the United States made it all too clear that that country “is no longer in touch with reality.” The US, as the host country of the UN, should do some serious “soul searching” and ask why it is sometimes entirely isolated from the developing world, the Chinese delegate said.

-ENCL