Dollar drought leaves Sri Lanka groping in the dark

By Marwaan Macan-Markar

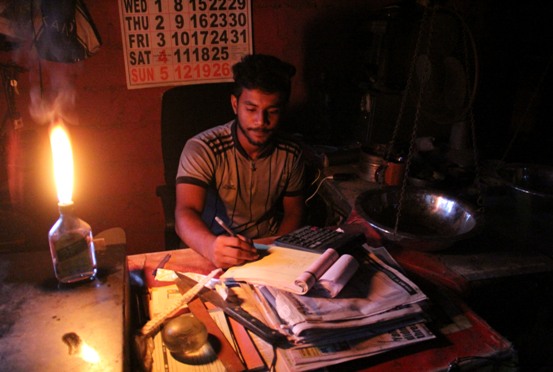

COLOMBO — As Sri Lanka’s dollar scarcity worsens, a fresh crop of unusual signs has surfaced about spreading shortages of basic goods. “Candles not available due to gas shortage” was one. It was placed at St. Anthony’s church, located in a mixed commercial and residential quarter of Colombo.

The significance of the announcement was not lost on regular worshippers. “Lighting candles is very much part of one’s worship in this church,” said a disappointed mother of two following her visit to the church this week. “I have been visiting this church for over 25 years — never have they not had candles!”

As homes seek light in the wake of rolling power outages, candles are one of a growing list of domestic items that have vanished from the shelves of supermarkets. They also include powdered milk, a favourite addition to a cup of tea, the national drink. Those lucky enough to get access to a few remaining packets share details of their find in whispers, as if discussing contraband items.

The lack of candles is not the only indication of the debt-strapped South Asian nation’s inability to cough up foreign exchange to pay for imported oil to run generators of the state’s energy utility. Government ministers in the ultra-nationalist administration of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa have kept the country on edge about dark nights ahead with public spats over the country’s energy security.

“I have instructed the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation to give 10,000 tonnes of oil to the Ceylon Electricity Board,” Energy Minister Udaya Gammanpila told reporters on Wednesday (19), referring to a state utility that uses the Indian Ocean island’s former name. “The CEB needs about 1,500 tonnes a day and this will be enough for eight days.”

In return, Power Minister Gamini Lokuge has been spinning another message, assuring the public that his officials are committed to uninterrupted power supplies. The country will be free of “power cuts” by the end of the month, he told the local media.

But power outages are in the cards, seasoned observers warned, in the wake of the Rajapaksa governments decision this week to dip into the country’s dwindling foreign reserves to pay a $500 million sovereign bond, which matured on January 18. That cut off the flow of limited foreign exchange to pay for a long list of imports, including oil, they said.

“We were already short of fuel but we decided to pay the debt,” said Nishan de Mel, executive director of Verite Research, a Colombo-based think tank. “In any kind of tough situation you should share the pain … you shouldn’t frontload the pain on the country — putting more pain on the country and less on the creditors.”

The government’s decision to favour creditors has brought Sri Lanka’s dollar dilemma into sharp relief. Finance Minister Basil Rajapaksa, the younger brother of the president, has said the country’s total external debt for 2022 is $6.9 billion, including a $1 billion sovereign bond maturing in July. The country began the year with only $1.6 billion in usable foreign reserves, with an additional $1.5 billion drawn from a swap with the People’s Bank of China, which, commercial banking sources say, cannot be used to pay debts to non-Chinese entities.

A new report by the World Bank suggests stronger headwinds in 2022, challenging the government’s exaggerated growth forecasts. Officials in Colombo have estimated that this year’s gross domestic product growth to hit 5.5% on the back of a revived tourism sector. That comes in the wake of claims that the country will reach an expected 4.5% growth in 2021.

But the World Bank places Sri Lanka as an economic laggard among its South Asian peers, forecasting growth of 2.1% in 2022, down from an expected 3.3% in 2021. This is the worst 2022 growth estimates in the region, which includes India, expected to grow by 8.3%; Bangladesh, to grow by 6.4%; and Nepal, to grow by 3.9%. South Asia’s regional projected growth will accelerate to 7.6% in 2022, the World Bank says in its ‘Global Economic Prospects’ report, released last week.

The early signs that Sri Lanka was running out of dollars first surfaced in mid-2020, when the country was shut out from accessing international capital markets to raise dollars through sovereign bonds to refinance its bulging foreign debt, an estimated $35 billion in the $81 billion economy. It followed a massive tax cut by the newly elected Rajapaksa government in late 2019 to boost the economy, which in turn worsened the budget deficit. That spooked international ratings agencies, according to analysts.

“Ever since the ratings agencies’ downgrade in mid-2020 to CCC the alarm bells should have gone off, because we lost access to the markets so we could not refinance and roll-over the debt,” said Murtaza Jafferjee, managing director of JB Securities, a financial consultancy in Colombo. “The scarcity of dollars will only get worse from now on.”

Several key numbers illustrate that the inflow of foreign exchange is far from stellar. Foreign direct investment, which the Rajapaksa government flagged as an alternative to foreign borrowing, has only trickled in, with the first half of 2021 attracting a mere $398 million, according to the Central Bank of Sri Lanka. The country’s Board of Investment had set its sights on securing $1 billion by the end of 2021, an ambitious target by the state’s premier foreign invest agency after a sub-par record of attracting only $550 million in 2020, down from $793 million the previous year.

A host of factors have added to the dollar woes. The country’s persistent trade deficit has been averaging $10 billion annually in recent years; tourism has slumped due to COVID-19; and a government plan to raise $1.5 billion by offering high-value properties in Colombo to foreign investors has struggled to attract interest. “We have never felt such a dollar crunch like this,” remarked a veteran commercial banker. “Importers have been running around the last three months to check which commercial banks have dollars.”

The Port of Colombo affirms that sentiment. Containers loaded with goods are piling up as importers are unable to secure dollars to clear them, according to shipping industry sources. Oil shipments at the country’s busiest harbour are also tied up, waiting for the dollar tap to open.

– Marwaan Macan-Markar, Asia regional correspondent asia.nikkei.com where this article was originally featured