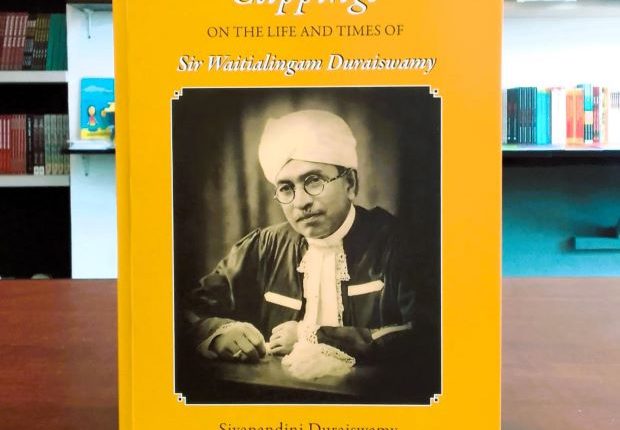

The leader, the visionary, the human being par excellence

Observations by Prof. Arjuna Parakrama on Clippings on the Life and Times of Sir Waitialingam Duraiswamy’

Good afternoon, everyone, I am indeed honoured and even a little abashed at standing before you to speak today on the occasion of the launching of the volume ‘Clippings’. However, I have rather foolishly taken this on, not because I think I am anywhere near an appropriate choice, but because I think the issues that Sir Waitialingam Duraiswamy’s life and times present us are too important to let slip away. The principles and values, the worldview and character, even the gentle foibles, of Sir Waitialingam provide for those who are willing to listen, for those who still wish to hear, perhaps, one of the few alternatives tenuous, fragile, and fraught, that may lead us back to sanity and later on to equality with justice. It is because of this fragile hope and belief that I stand diffidently before you today to make a few observations on Sir Waitialingam Duraiswamy, the leader, the visionary, the human being par excellence.

I would like to confine my brief remarks to four areas in all of which, I believe Sir Waitialingam had in his inimitable, quiet but firm, steadfast, way shown us a path and a perspective that today, more than ever before, is worth understanding and attempting to follow. I shall try to use his religio-cultural tradition, not mine, to explain his ways and values, in part because that would provide the greatest explanatory power, and because for too long we have remained trapped, both wittingly and unwittingly in our own cultural and religious traditions, which then serve to divide and exclude. If we are to be serious about integration we have no right to the luxury of owning only one of many threads in our national mosaic.

To this end, let me begin with an overall assessment of Sir Waitialingam as I believe and see captured in the extraordinary poem found in the Puraananuru (182) by Ilam Peruvaiyuti in the extraordinary translation by A.K. Ramanujan. Let me read what I think is a beautiful summary of the kind of man I believe Sir Waitialingam was, as well as of the kind role men like him play in society.

The World Lives Because

This world lives

because

some men

do not eat alone,

not even when they get

the sweet ambrosia of the gods;

they’ve no anger in them,

they fear evils other men fear

but never sleep over them;

give their lives for honour,

will not touch a gift of whole worlds

if tainted;

there’s no faintness in their hearts

and they do not strive

for themselves.

Because such men are,

This world is.

Ilam Peruvaiyuthi, Puranaanuuru 182

This is both the potential and catastrophe of our times. The Sangam poetry of over 2000 years ago can be excused for focusing only on men, but certainly not us in Sri Lanka today. We have no women or men of this kind here anymore, at least in positions of authority and power, so our world is in danger of disintegrating – of not being ‘is’ any longer. It ‘was’ but it ‘isn’t’ now, and alas, we must all share some blame for this. My humble intervention today, is, then, a celebration of Sir Waitialingam’s life and values, as well as the performance of obsequies for a lost time, a bereft space, trapped in the past.

This should not be: systems need to be in place, institutions need to function, which go beyond individuals. For the author of the Thirukura, the matter was strikingly simpler:

The welfare of the world is in the goodness of those who govern.

It depends on the nature that resides within. –Verse 982

We must believe otherwise, but yet, without visionary leaders of the kind of Sir Waitialingam, we are doomed to echo Antonio Gramsci, referring to a different kind of fascism, of which I shall use the liberal translation of Gramsci popularized by Slavoj Žižek (2010).

“The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters.”

Systems have failed us, as have leaders, and echoing Shakespeare’ Prospero, we must take responsibility for “this thing of darkness / which [we] acknowledge [ours].”

Beginning with a Kural that sums up greatness in our sense, I will attempt to take stock of the lessons we can learn from the life of Sir Waitialingam on the occasion of the launch of Clippings.

Love, modesty, beneficence, benignant grace,

With truth, are pillars five of perfect virtue’s resting-place. –The Virtuous: Verse 983

Thus, the core values that I would like to focus on today as lessons and examples include integrity, giving, impartiality, and simplicity.

INTEGRITY

The question of integrity, fundamental in its absence, in its utter dereliction today, is embodied in Sir Waitialingam’s philosophy and practice of life. As Sir Francis Molamure writes in 1936:

“Mr. Duraiswamy proved his sterling worth and political integrity during the term of the Reformed Council of 1924. There is no doubt that he is the outstanding political figure among the Tamils.” – A.F. Molamure, Times of Ceylon Feb 1936 [p. 101]

Dr N. M. Perera in his Vote of Condolence reproduced in the Hansard of 1966 has this to say:

“He was a man of whom we can be proud, and the Legislature can be proud, and certainly we in this country can be proud. He had a sense of fair play, justice and a high sense of integrity and, above all, he was a genial person who always discussed matters frankly with all Members in the Speaker’s Chamber, listened to their difficulties and pointed out ways of solving their difficulties. In essence, he was an ideal Speaker. All of us looked up to him to maintain the high honour and dignity that was expected of the Chair.

We have lost, as the hon. Member who spoke on behalf of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party said, one of the old politicians of this country. He was one of the last links between the old and the new.” – Hansard of 1966: Dr N. M. Perera [Vote of Condolence]

The point to be made here is that integrity is not a matter of avoidance, integrity is not a matter of turning the other side and becoming consciously unaware of what is going on. Integrity is an engagement, it is, as Dr Perera says, frank engagement on key matters, listening to difficulties, and solving problems. Sir Waitialingam was someone who confronted injustice, inequality and wrongs and actively helped to right these wrongs. Integrity is not passive, it is not the absence of corruption, nepotism, kleptocracy nor the avoidance of personal gain: it is the active campaigning and active engagement against those cancers that affect integrity, be they people or institutions, ideologies or fiefdoms, whether they seek refuge in culture and tradition, or hierarchy and protocol. But, this integrity must be lived and practised: it is not merely a slogan for the hard times in opposition backbenches, for garnering votes at elections. In this sense, the integrity embodied by Sir Waitialingam was tied to his dignity and moral compass as surely as his religion and family values.

The Thirukural, in verse 119 expresses this quite poignantly:

Speech uttered without bias is integrity,

Provided no unspoken bias hides in the heart. – Verse 119

This is the crux of the problem which goes beyond avoidance, subterfuge hypocrisy and so on. I will have occasion to talk about the heart of greatness later on, but let me move on now.

GIVING

Next, I would like to focus on the notion of giving, which is not charity, but which is an understanding of equality, a redressing of injustice, a restoration of the level playing field. And, I must say that again I have to rely on a translation of the Thirukural, verse 218, which I think is important because one does not have to be hugely financially rich to have that sense of giving. In fact, it is a sad truism to say those who are hugely financially rich do not indulge in such giving today, but in taking more and more.

Here is the Kural:

Those who deeply know duty do not neglect giving,

Even in their own unprosperous season. –Verse 218

In his quiet retirement, he was as prone to giving as he was earlier. And in fact, his role as the Speaker – even though he was scrupulous to the point of not being involved officially in either party or politics – provides a shining counter-example to the current dispensation. Here, he was able through his good offices, his persuasive powers and the force of his character to enable the people in the islands, particularly in Delft, to obtain services that were unthought of earlier. Motorized boats, piers and so on.

But, most importantly, it was not done irregularly, it was not done unfairly, it was not done in order to canvas or bargain or buy votes; it was done because it was a duty, a duty seen as a labour of love and, crucially, it was something for which he never took credit. These I think are unique examples to our present and future generations.

Again, from the Thirukural

The benevolent expect no return for their dutiful giving.

How can the world ever repay the rain cloud? -Verse 211

Sir Waitialingam was a rain cloud to the islands, to the Jaffna peninsula, to the people who came to him or of whom he recognized a hope, and this was remarkable because it was not part of a quid pro quo, it was not a political circus. It was quiet, it was discreet, and it addressed the need of the hour.

“I feel so helpless, so small, so unable to do what is expected of me. In my home, I feel

strongly about the great wants of our people and often felt and wept that something should be done to raise our people’s standard of living, education and physical conditions. This frail body is unable to cope with the stupendous work that lies before me.” [p. 146]

IMPARTIALITY

Perhaps the most difficult principle to engage because he and I like many are ambiguous about its benefits or to be precise the greater benefit was Sir Waitialingam’s impartiality. The moment he became the Speaker of the State Council, he ceased to be the uncontested MP for Kayts, he ceased to be the representative of the Tamil people, he ceased to be a son of the soil. He identified himself, and he became, one with all the interests of all the people in the country.

D.B Dhanapala puts this quite beautifully and quite accurately in his description of the early stages of Sir Waitialingam’s tenure when he states:

“It is a lie to say the Speaker takes no sides. As a matter of fact, he takes sides more than any man on the floor of the House. But he takes all the sides available on any question at different times.

“He seems as much concerned and interested in the halting sentences of the most insignificant backbencher as the desperate defence put up by the leader of the House.

“The smile of interest is thin; the nod of understanding is slight. But there is nothing mechanical about these encouragements on the part of the Speaker, His behaviour when on the chair seems to be always in evening dress, as it were. There is a formal dignity not without grace that clothes the few words he sometimes utters, the smile he often proffers and even the raising of the eyebrows he but seldom affects.”

I think it is worth understanding that impartiality taken to the extreme in order to reconcile his understanding of the principle role and function of the Speaker, may be a disadvantage or even a tragedy of our times.

“Mr Duraiswamy does not speak too much. And whenever he does speak, he says the right thing. There is also a complete lack of what is called ‘side’ in his behaviour which makes his personality unobtrusive in the House. His rulings are often firm. …

“But his firmness is not off his own bat. He takes the sense of the House when he is in doubt. At other times he seems to scent the feeling prevalent. But in whatever he does there is the touch of the sure hand, the ring of the decided mind about it.” [pp. 42- 43]

Unfortunately, when Ceylon obtained the services of the most important Speaker and the first citizen in Sir Waitialingam Duraiswamy, we also lost a powerful advocate, a strong voice for united Ceylon whose liberalism found him putting aside less important ethnic, and cultural differences at that crucial juncture, and this loss I think proved fundamental in the history that unfolded at the time. The trade-off was identified by many as the quid pro quo for his being elected and in his demonstrating so exemplary a level of impartiality for 11 crucial years in that office.

However one wishes to rationalize it, Sir Waitialingam’s eloquence in the House, his ability to reason and explain using his judicial training, and his ability to analyze and understand an issue were sadly missed. And unfortunately, he too was well aware of this. Mr. Dhanapala observes

“At my last interview with him, on the eve of his departure to England, I found him greatly perturbed regarding the trend of events. He felt all the worse because as Speaker he was helpless.

“With the highest conceptions of the duties of the Office he holds, the Speaker would not take part in politics even behind the scenes. But a Speaker has his own opinions unexpressed in public.” [pp. 46-47]

The issue there was he was unhappy because of the communal turn of politics at that time. He was unhappy and prescient about what would happen in future, and it did. It led him to exclude himself from politics and public life after 1947. Being scrupulous and a stickler for due process, he eschewed working in the unofficial Bar as well, proving all those wrong, including Dhanapala, who felt that his political career would continue to blossom. However, exclusionary nationalist politics had overtaken the country, inevitably, and from the point of view of non-Sinhala groups, justifiably, but this was not a political arena that Sir Waitialingam trusted or valued, and in turn, it was not one in which his worth was duly recognized.

Dr N.M. Perera states in 1966: how wrong he was proven to be:

“It used to be a common theme of discussion between himself and myself as to how best the problem of communal tension that seemed to prevail in the last decade or so could be solved. I always maintained – and I think he agreed – that this was a passing phase.”

I don’t think that he was right even about Sir Waitialingam’s view: my evidence, beyond the circumstantial, is that despite referring to this as “a common theme of discussion” he is as yet unsure of Sir Waitialingam’s view on the subject of such frequent discussion. Perhaps politeness intervened here!

REFINED SIMPLICITY

In an extraordinarily felicitous phrase, D. B. Dhanapala captures what I consider to be the essence of Sir Waitialingam’s personal uniqueness vis-à-vis the other politicians of his time. All of them were elite, educated sufficiently and comfortably westernized. Yet, Sir Waitialingam had that quality of refined simplicity which he bore with aplomb and flair.

In the words of Dhanapala,

“In their dealings with their own countrymen, the best class of Sinhalese has copied the superior manner in which the European in the east treats the Asiatic. They are seldom able to get away from that sahib brusqueness, and not many single-use politicians will ever attain that refined simplicity of the high-class Dravidian as personified in Mr Duraiswamy. . . . Here is a man without all the complexities of pose and pomp — who talks to his inferiors with the same respect as he would to equals. This wiry athletic Dravidian in a long coat, who sleeps on a hard plank to this day, is prouder of his fame as a farmer than of his name as a politician or lawyer.”

The point I wish to make is that when Sir Waitilingam speaks of a united Ceylon and its shared heritage, he’s not like some others of his time speaking about Oxford or Cambridge, Victorian values, a Christian ethos or even the unabashedly upper-class Colombo milieu of like-minded Sinhala, Tamil, Muslim and Burgher fraternities conjoined by the old school tie, More British than the British themselves, as Macaulay planned a century earlier in his infamous Minute on Indian Education (Not accidentally the year that Royal College – then The Colombo Academy – was founded): “We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern, -a class of persons Indian in blood and colour, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect.”

This simplicity is neither contrived nor natural. Paradoxically it is a learned and deliberately chosen simplicity based on values and beliefs. The frills of office, of colonialist public life were not beyond Sir Waitialingam’s enjoyment. He could take it or leave it. He was most comfortable in Jaffna in his home with his family and friends in communion with his guru among his people. The example most illustrative of this point is his rapid departure from Colombo to Jaffna on returning after being knighted so that he can be with his family and well-wishers. His remark on that occasion is symptomatic of that refined simplicity the eschewing of pomp and pageantry in favour of deeply rooted, understated yet firmly held beliefs and practices.

“I could not resist the strong urge to be in Jaffna a minute longer and I am here now among you,” he said by way of explaining to his friends the reason for his hurried departure from Colombo soon after his return from England.” [p. 139]

Conclusion

Destiny’s last days may surge with oceanic change,

Yet men deemed perfectly good remain, like the shore, unchanged. -Verse 989

Manik de Silva in his preface notes that “this is a small world.” We now need to confront the inescapable fact that this is not so any longer. There’s both good and bad in this new reality, notwithstanding its monsters. A larger world allows for greater participation, widespread upward social mobility and the drastic reduction of old class-caste hierarchies that dominated this small world in the past. Yet, while saluting and championing this sea change, we must find room for all that was the best of that past. Sir Waitialingam was certainly, irrefutably among the exemplars we must learn to cherish, and unlearn our own present madness to understand, value and emulate.

His life remains an antidote to the brutes of our epoch, beautifully captured in this new translation by Dr S. V. Kasynathan of Kural 1020, one of the most poignant reminders of our current predicament.

The movement of men without shame within their heart

Is like wooden puppets on a string pretending to be alive. [Kural 1020]

After such knowledge, what forgiveness?

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.