Crimes against journalists and entrenched impunity

By Ruki Fernando

The Permanent People’s Tribunal in The Hague (Netherlands) has commenced hearings into the murder of journalist and editor Lasantha Wickrematunge based on an indictment presented by a coalition of international press freedom organizations. The hearing is focusing on the overall context of crimes against journalists and impunity in Sri Lanka.

Forty four names of journalists and media workers killed or disappeared between 2004 and 2010, the majority of who are Tamils, was read out by Journalists for Democracy in Sri Lanka while acknowledging there had been many more killed and disappeared before that. The indictment on Lasantha’s case at the tribunal notes that his murder was part of systematic attacks on journalists during the civil war. The hearing focuses on his murder.

The tribunal is also hearing cases of Syrian and Mexican journalists who were killed. The opening session was on November 2, 2021 and the closing session is on June 20, 2022 where the panel of judges will pronounce its preliminary judgment.

Many journalists have been killed or subjected to enforced disappearances since the 1980s with the Jayewardene-Premadasa led United National Party (UNP) governments of 1977 to 1994 and Rajapaksa led United People’s Freedom Alliance (UPFA) government of 2006 to 2014 being the worst. Many have been arrested, detained, assaulted, threatened, intimidated and harassed over the decades under all governments.

Media institutions have been subjected to arson and legal actions with the Sunday Leader, the English paper Lasantha founded and edited, and the Uthayan, the most popular Tamil newspaper in the war-ravaged North, being among the worst affected. In the aftermath of a government crackdown on a large protest outside the president’s house in the outskirts of Colombo on March 31 this year, journalists revealed that the police chief had ordered an investigation into a major private television channel, News First, in an effort to blame the channel’s live broadcast of the previous night’s protests for the unrest that occurred.

Impunity has served as a licence for continuing crimes and violence against journalists. Many have subject themselves to self-censorship, and many have fled the country even this year.

According to the Free Media Movement (FMM), not a single person has been convicted for crimes against journalists and only two cases have reached the prosecution stage. In one of them, the murder of journalist Mylvaganam Nimalarajan in Jaffna in October 2000, media reported that the Attorney General has instructed the courts not to continue the case against the suspects last year. The other is the case of the disappearance of journalist and cartoonist Prageeth Eknaligoda in January 2010, which saw some progress towards justice. Much of the progress, including the indictments against army personnel, was during the Yahapalanaya government elected in 2015. But after the return to power of Rajapaksa family (under whose watch Eknaligoda disappeared) the case is moving backwards rather than forward. The Rajapaksas pledged not to prosecute war heroes (i.e. military personnel), a top investigator went into exile and his chief overseeing the investigations has been arrested and detained.

Even the minimum progress in investigations, arrests and prosecutions seen under the previous government in a few high profile cases that happened in Colombo was absent in cases involving Tamil journalists.

Presidential Commission of Inquiry promoting impunity

The 20th Amendment to the Constitution in 2020 providing the president with absolute discretion in appointing the Attorney General (the prosecutor) and judges to higher courts further compromised seeking justice in the criminal justice system.

Within months of being elected, the current president appointed a Presidential Commission of Inquiry to look into allegations of political victimization under the previous government (2015–2019). This has become a project to promote impunity, including for crimes against journalists. According to a study by the Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA), the commission had recommended the withdrawal of charges against a senior police officer accused of concealing evidence in Wickrematunge murder and some of the accused on whom indictments have been served in the ongoing court case in the Eknaligoda disappearance.

Similar recommendations have been made in relation to those who have been implicated in abduction and torture of journalist Keith Noyahr. The Commission had also instructed the Attorney General’s Department to halt investigations and prosecutions in courts in relation to cases it was probing, including the disappearance of Eknaligod and recommended offering Foreign Service post to the main accused in the High Court trial. A key prosecution witness in the Eknaligoda case defied a court order and appeared before the Commission to claim his previous testimony had been made under duress.

In all the cases, the Commission has recommended actions against police officers who had uncovered evidence about the involvement of police and military. Overall, the approach of the Commission has been to frame investigations and prosecutions against grave crimes (including against journalists) implicating politicians and military as political victimization.

CPA has also indicated that in April 2021, then Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa tabled a resolution in Parliament for the implementation of the recommendations of the commission seeking the dismissal of several cases pending before courts and the initiation of criminal prosecution of police officers, lawyers, officers of the Attorney General’s Department, witnesses and others involved in the cases mentioned in the commission report.

Justice, protests and international initiatives

The Hague Tribunal coincides with the historic people’s protests, which led to the resignation of Prime Minister (and former President) Mahinda Rajapaksa on Monday (9), in addition to the resignation of three others from the Rajapaksa family who had held ministerial positions. The largest and most prominent protest site has been at Colombo’s Galle Face Green bordering the Presidential Secretariat, named by protesters as ‘GotaGoGama’, meaning a village set up to ensure the resignation of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

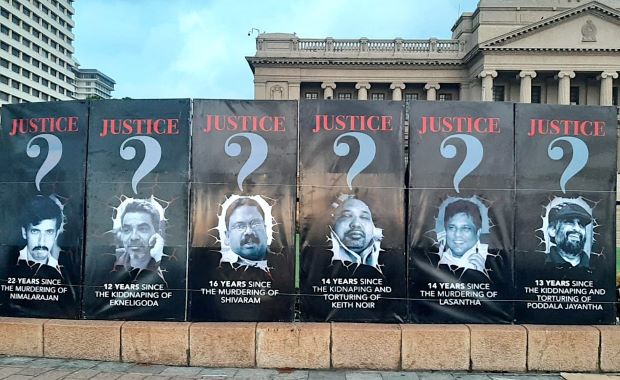

On April 11, the third continuous day of protests at the Galle Face, I saw a protester holding a sign demanding justice for the murder of Lasantha Wickrematunge. Another protestor held a sign with the phrase ‘Satakayo Gathakayo’, which implies that those who wear shawls like most in the Rajapaksa family do, are killers. It was the first time I had seen this slogan since the funeral of Lasantha more than 13 years ago. It has become a popular slogan across the country at protest sites. Another placard that had photos of Lasantha and Prageeth Eknaligoda read ‘Hey Rajapaksas do you remember us, we are in the frontline of the protest’. Huge placards of murdered, tortured and disappeared journalists were placed on the fence of the Presidential Secretariat and were re-installed when they were removed and destroyed. Journalists have also held protests at the site.

However, it must be noted that the protests were triggered by an unprecedented economic crisis and most of placards and slogans deal with financial crimes, corruption and the economic crisis.

Uncertainties and hopes

Protesters on the streets of Colombo have been steadfast about insisting on President Gotabaya Rajapaksa leaving office and not having anyone from the Rajapaksa clan in any interim governance structures. They are also insisting on radical long term institutional, legal, cultural and political reform. Part of such reform is about an independent and effective criminal justice system, including the police, prosecutors and judiciary. Until and unless this happens, prospects for justice appears bleak.

International initiatives such as the Hague Tribunal have become significant in this context as survivors of crimes and families of victims search for justice. The Hague Tribunal hearings follow other international initiatives to seek justice for Lasantha’s murder in January 2009. These include the filing of a case in the United States in 2019 and a complaint to the UN Human Rights Committee in 2021 by Lasantha’s daughter, Ahimsa Wickrematunge, after a decade of waiting for justice in Sri Lanka under two different governments. The limited progress in the Eknaligoda case is primarily due to an exceptionally courageous and determined campaign by his wife Sandya. The international campaigns she initiated and inspired would have been a significant factor in progress in domestic justice.

The Hague People’s Tribunal doesn’t enjoy formal judicial authority and cannot make legally binding decisions. But its hearings and decisions may provide some solace to desperate survivors and families of victims who have been denied justice for so long in their own countries. It may also serve as social and political pressure for more formal judicial processes and deserves maximum support, especially from the journalistic community.

More importantly, this moment of uncertainty and hope could be an opportunity for Sri Lankans, especially journalists, media freedom organizations, journalists’ unions and media institutions that employ journalists and media workers, bodies such as the editors’ guild and broadcasters’ guild, to reflect on what needs to be done to address impunity for crimes against journalists and create a more safe, free and enabling environment for journalism.

– Ruki Fernando is a human rights activist and this article was originally featured on groundviews.org