WHO says Omicron poses a ‘very high’ risk globally

By Nick Cumming Bruce

GENEVA – The World Health Organization (WHO) warned Monday (29) that global risks posed by the new Omicron variant of the coronavirus were “very high,” despite significant questions about the variant itself. Still, countries around the world rushed to defend against its spread with a cascade of border closures and travel restrictions that recalled the earliest days of the pandemic.

Scotland and Portugal identified new cases of the highly mutated variant, and Japan joined Israel and Morocco in banning all foreign visitors, even as scientists cautioned that the extent of the threat posed by Omicron remained unknown — and as the patchwork of travel measures were so far proving unable to stop its spread.

Many of the restrictions aimed at corralling Omicron, which was first identified last week by researchers in South Africa, were aimed at travellers from southern Africa, drawing accusations that Western countries were discriminating against a region that has already been set back by vaccine shortages caused by rich nations hoarding doses.

In a technical briefing note to member countries, the WHO urged national authorities to step up surveillance, testing and vaccinations, reinforcing the key findings that led its technical advisers Friday (26) to label Omicron a “variant of concern”.

The agency warned that the variant’s “high number of mutations” — including up to 32 variations in the spike protein — meant that “there could be future surges of COVID-19, which could have severe consequences”.

Experts including Dr. Anthony Fauci, a top adviser to President Joe Biden, have said that it could be two weeks or longer before more information about the variant’s transmissibility, and the severity of illness it causes, is available. So far, scientists believe that Omicron’s mutations could allow it to spread more easily than prior versions of the virus, but that existing vaccines are likely to offer protection from severe illness and death.

Still, the makers of the two most effective vaccines, Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, were preparing to reformulate their shots if necessary. And some countries, including Britain, were preparing to expand booster programs to protect more people.

The WHO stressed the need for countries to accelerate vaccinations against COVID as rapidly as possible, particularly for vulnerable populations and for those who are unvaccinated or not fully vaccinated. It also called on health authorities to strengthen surveillance and field investigations, including community testing, to better determine Omicron’s characteristics.

The recommendation underscored that the steps taken by some countries to wind down testing and tracing capacity in recent months — as the pandemic appeared to be receding thanks to rising vaccination rates — are moving in the wrong direction.

“Testing and tracing remains fundamental to managing this pandemic and really understanding what you’re dealing with,” said Margaret Harris, a spokeswoman for the agency. “We’re asking all countries to really look for this variant, to look if people who have got it are ending up in hospital and if people who are fully vaccinated are ending up in hospital.”

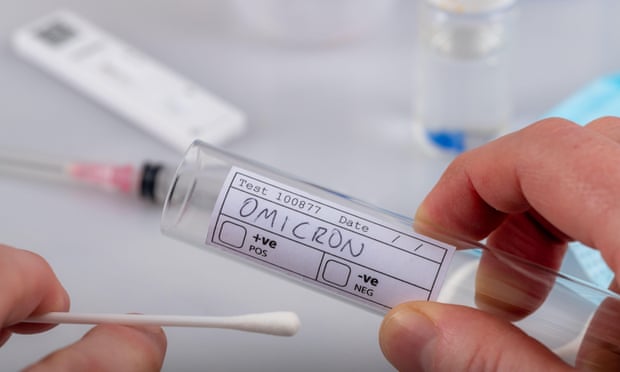

The briefing note adds that PCR tests are an efficient tool for detecting the new variant because they do not require as long a wait for an outcome as genetic sequencing tests that require laboratory capacity not available in all countries.

“It’s very good news,” Harris said. “You can much more quickly spot who’s got it.”

But while the agency had previously cautioned against imposing travel bans, the briefing note took a more flexible line, calling for a “risk-based approach” to travel restrictions that could include modified testing and quarantine requirements. The agency said it would issue more detailed travel advice in the coming days.

At the same time, WHO member states were beginning a three-day meeting to discuss a global agreement on how to deal with pandemics, a deal long pushed by the agency to address weaknesses in the response to COVID-19. The European Union has argued for a treaty that would require greater information sharing and vaccine equity, but the United States has sought to keep open the option of an agreement that would not be legally binding.

-New York Times