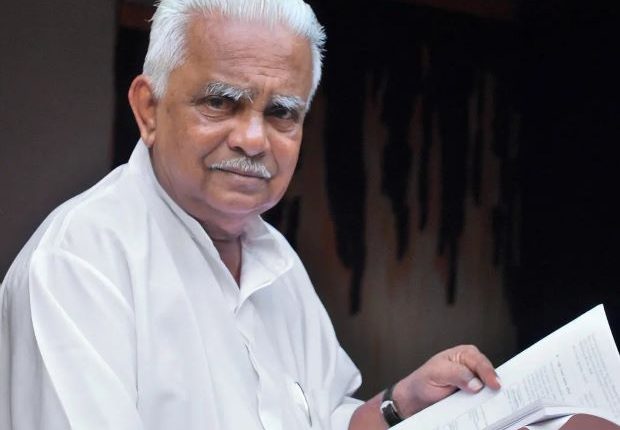

A.T. Ariyaratne, the man who preached brotherhood across ethnic divides

By Adam Nossiter

A.T. Ariyaratne, a Sri Lankan who fought to alleviate the terrible living conditions of his country’s rural poor, creating a Buddhism-inspired social services organization that operates in thousands of villages, died on April 16 in Colombo, Sri Lanka’s capital. He was 92.

His death, at a hospital, was confirmed by his son Dr. Vinya Ariyaratne, in an interview.

Sometimes styled in the country’s media as a Sri Lankan Mahatma Gandhi, Ariyaratne preached brotherhood across ethnic divides and, with the help of volunteer labour and outside donations, brought aid to Sri Lankan villagers struggling with poor sanitation, insufficient food, broken roads and inadequate shelters and schools.

Hailed as a national hero and modelling himself on Ghandi’s ideals, he grew his Sarvodaya, or ‘Awakening of All’, movement from a presence in a handful of villages to operations in more than 5,000 of them a half-century later, digging wells, building schools, fixing roads, providing credit and more.

‘Sarvodaya’,’ a term first used by Gandhi in India and inspired by the writings of the English critic and essayist John Ruskin, meant “the well-being of all,” especially the least fortunate, in Ariyaratne’s interpretation, as he explained in an essay in the anthology ‘The Sri Lanka Reader’. Ruskin’s essay ‘Unto This Last’, with its egalitarian, anticapitalist underpinnings, was a particular inspiration.

But Ariyaratne worked primarily in a time and a place largely unreceptive to his peace message: during Sri Lanka’s vicious civil war from 1983 to 2009, in which mass murders, civilian executions and torture were the norm. The war limited his impact, according to some scholars and observers, as the country reeled from repeated bouts of violent conflict between the majority Sinhalese Buddhists, like Ariyaratne, and the minority Tamils, mostly Hindu.

In the midst of the war, in 2001, Barbara Crossette, a former foreign correspondent for The New York Times, wrote in the Buddhist magazine Tricycle, “Sarvodaya’s success has been small, and the carnage continues”.

Much of the Sarvodaya Shramadana Movement was dismissed as “naïve and unrealistic” by the Oxford and Princeton scholars Richard Gombrich and Gananath Obeyesekere in their 1988 book, ‘Buddhism Transformed’.’

But others, pointing to Sarvodaya’s village-level projects, insist that Ariyaratne’s movement had positively affected thousands of Sri Lankans and that his Buddhist precept of respecting all lives had helped his country through a relatively peaceful period since the end of the war.

“The legacy was to provide practical ways people could address the problem of suffering,” John Clifford Holt, a veteran Sri Lanka scholar and emeritus professor at Bowdoin College, said in an interview. “He provided a progressive, this-worldly orientation to Buddhism. He took these ideas and inspired the volunteers. They built roads and dug wells, they provided microfinance for women.”

In Sri Lanka, observers and analysts acknowledged that Ariyaratne’s efforts to lessen the country’s strife had uneven results.

“He tried to ensure that if there was conflict, it was transformed into coexistence,” Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu, executive director of the Centre for Policy Alternatives in Colombo, said in an interview. “Ariyaratne’s work has not been able to prevent that. But where he’s seen it happening, he’s intervened, at the local level.”

Sarvodaya had “an impact on bringing Tamils and Sinhalese together in various parts of the country, but it was not large enough to really make a big dent,” said Radhika Coomaraswamy, a Sri Lankan and former UN special representative for children and armed conflict.

Still, Ariyaratne’s efforts to foster peace were nothing if not dogged. Soon after the first deadly anti-Tamil riots in Colombo in 1983, “Sarvodaya began to organize camps for the refugees and aid for the victims,” George D. Bond wrote in ‘Buddhism at Work’, his 2003 study of the movement.

Ariyaratne, he added, used his “village network to provide food for the refugees, construct medical clinics, construct shelters and rebuild houses and schools.” He also established preschools and credit facilities for villagers as well as nutrition centres for children and the elderly.

As the violence continued, he organized a peace march in the south of the island that was stopped after only a few miles on the order of the president at the time, J. R. Jayewardene. Ariyaratne organized other peace marches in the following years, often to the irritation of the country’s leaders, who resented his popularity.

In 1994, travelling to the country’s North as a mediator, he met with leaders of the Tamil rebel movement, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). “It was not successful,” Jehan Perera, executive director of Sri Lanka’s National Peace Council, who was part of the mission, recalled in an interview.

Sarvodaya organized a mass meditation for peace in 2002 that was similarly ineffectual, though it remarkably attracted 650,000 people across ethnic divides, according to Bond. It wasn’t until 2009 that the government brutally stamped out the remnants of the rebel movement, engaging in more civilian massacres.

Ariyaratne had early on shed any illusions about the Buddhist underpinnings of the Sri Lankan state. “Even though, historically and culturally, Sri Lanka may claim to be Buddhist,” he wrote in 1987, “in my opinion, certainly the way political and economic structures are instituted and managed today, they can hardly be called Buddhist either in precept or practice.”

Ahangamage Tudor Ariyaratne was born on Nov. 5, 1931, in the town of Unawatuna, British Ceylon, as the country was known before it gained independence. He was the son of Ahangamage Hendrick Jinadasa, a wholesale trader, and Rosalina Gajadheera Arachchi, who managed the household. He attended Mahinda College in nearby Galle and received a degree in economics, education and Sinhala from Vidyodaya University in 1968.

Years before, Ariyaratne had embarked on a trip that transformed him and became the foundation of his movement. In December 1958, while teaching science at Nalanda College, a leading secondary school in Colombo, he took 40 of his students and 12 teachers to a nearby low-caste village, Kanatoluwa, where they spent days helping its residents in various ways, including digging wells, building latrines and repairing its school. Thus was born Ariyaratne’s concept of ‘Shramadana’, or ‘Gift of Labour’, a project that grew throughout the 1960s to encompass hundreds of voluntary labour camps, as Bond characterized them.

Ariyaratne saw Shramadana as transformative for both the movement’s thousands of volunteers and the villages themselves. His goal, he wrote, was “a dynamic nonviolent revolution which is not a transfer of political economic or social power from one party or class to another but the transfer of all such power to the people.”

By the early 1970s, he was attracting funding from the Netherlands, Germany, and Switzerland. Sarvodaya became the country’s largest nongovernmental organization, according to Bond. Though clashes with the government over the movement’s nonviolent stance led some outside donors to withdraw funding for periods, Ariyaratne always managed to bounce back.

In addition to his son, he is survived by his wife, Neetha Ariyaratne; three daughters, Charika Marasinghe, Sadeeva de Silva and Nimna Ganegama; two other sons, Jeevan and Diyath; 12 grandchildren; and sister, Amara Peeris.

After his death, Ariyaratne was given a state funeral attended by the country’s president, Ranil Wickremesinghe, and prime minister, Dinesh Gunawardena.

“We see him as a model human being who attempted, amid great challenges, to bring people together,” Colombo’s Anglican bishop, Dushantha Rodrigo, said in an interview. “The war was orchestrated on very political lines. People were not given much of a chance, well-meaning people like him, who made attempts to bring about a peaceful settlement.”

-New York Times

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.