The World Cup that changed everything

By Tariq Panja and Rory Smith

Michel Platini was expecting a private audience with the president of France when he arrived for lunch on a cold day in November 2010. Instead, as Platini, a legendary French player who in retirement had risen to become one of the most powerful men in soccer, stepped into a lavish salon inside the president’s official residence, he noticed immediately that the man he had come to see, Nicolas Sarkozy, was absent.

Instead, Platini was directed toward a small group chatting across the room, and to a conversation that would alter the course of his career, stain his reputation, and forever change the sport to which he had dedicated his life.

Platini smiled as he was formally introduced to the lunch’s guests of honour: Sheikh Hamad bin Jassim bin Jabr al-Thani, the prime minister of Qatar, and Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani, who would, within a few years, replace his father as the country’s absolute ruler. The Qataris had come to Paris to discuss a plan that bordered on the fantastical: Their tiny, impossibly wealthy Gulf state wanted to host the World Cup.

Platini, a vice president of FIFA, soccer’s global governing body, had long been cool to the idea. A year earlier, he had told friends that he believed allowing Qatar — a country without any meaningful soccer tradition, one lacking basic infrastructure like stadiums — to stage the biggest sporting event in the world would prove disastrous for FIFA. Only two months previously, he had confided to a rival United States bid that he wanted the 2022 tournament to go “anywhere but Qatar”.

At some point that afternoon, though, Platini’s reservations melted away. What happened to change his mind over lunch with a late-arriving Sarkozy and the two Qataris remains, more than a decade later, resolutely obscure and fiercely contested. Platini himself has offered at least two distinct versions of events — in both he said his vote was his own choice, and not reflective of outside influence — and in 2019 he was detained, but not charged, by French investigators said to be looking into the meeting.

By then, though, the deal was done: A week after the lunch, inside a cavernous conference hall in Zurich, Qatar was confirmed as the host of the 2022 World Cup.

The world’s most popular sport has been reckoning with the consequences of that decision ever since.

American investigators and FIFA itself have since said multiple FIFA board members accepted bribes to swing the vote to Qatar. (Platini was not among them.) A broad corruption investigation into how FIFA conducts business led to dozens of arrests. Those cases and others helped bring down the entire leadership of FIFA, and almost toppled the institution itself.

But the decision also irrevocably altered the economics of top-flight soccer. Having won the World Cup, Qatar quickly moved to establish itself as a true power in the sport. Within a year of the lunch at the Élysée Palace, Qatari interests had bought the French team Paris St.-Germain, and a Qatari-owned sports network had begun pouring money into European soccer by buying up broadcasting rights. That influx of cash not only affected what top players earned and where they played: It also briefly threatened to drive an irreconcilable wedge between a handful of the sport’s richest teams and the rest of the game.

At the same time, it inspired a frenzy of construction as a tiny Gulf country was, in effect, remade in a stunning nation-building project that, according to human rights groups, cost thousands of migrant workers their lives, a figure Qatar rejects.

And now, with long-feared cultural disputes playing out, it has arrived at a point that once seemed unthinkable: hundreds of the world’s finest soccer players and more than 1 million fans gathering in a thumb-shaped peninsula in the Persian Gulf, ready for the tournament that changed the game.

The Bid That Broke FIFA

For much of the 20th century, Qatar was a barren Persian Gulf backwater better known for pearl diving than power politics. Its people were poor, lagging far behind their Saudi neighbours.

Then Qatar struck gas.

The discovery in 1971 of the world’s largest gas field led to the first transformation of Qatar: turning it into one of the wealthiest countries in the world, and emboldening its leaders to see their nation not just as an appendage of its wealthier neighbours, but as a true geopolitical rival. The quest to host the World Cup, then, was just another step: the chance to announce themselves, to tell their story, on a truly global stage.

Qatar has for years rejected criticisms of its effort to win the World Cup as jealousy or, worse, Western racism. But having the money and the ambition to host the tournament was one thing. Winning the right to do so was quite another. And in 2010, that was Qatar’s biggest problem.

A week or so before the two dozen members of FIFA’s executive committee — including Sepp Blatter, the FIFA president, and Platini — were scheduled to decide which of the five competing bids would win the right to host the 2022 World Cup, Harold Mayne-Nicholls landed in Zurich.

A suave, soccer-obsessed Chilean, Mayne-Nicholls wielded considerable power, at least in theory. He had led the inspection team dispatched by FIFA to assess each of the bidders, and the evaluation reports his team created had the potential to swing the vote.

His verdict on Qatar — the product of a three-day visit to Doha in September 2009 — was hardly a resounding endorsement. While the country had scaled back on some of its initial plans, which included building an artificial island big enough to be seen from space, the inspectors still harboured seemingly insurmountable doubts.

No. 1: Qatar was too small. “It was a huge problem for organization,” Mayne-Nicholls said. And No. 2: In the (Northern Hemisphere) summer, the traditional window for playing the World Cup, it was simply too hot.

Qatar had gamely tried to assuage those concerns by building a small stadium to demonstrate the futuristic air-conditioning system it said would ensure all of the games would be played in close to ideal conditions. Mayne-Nicholls was impressed, but the issue remained.

“The problem would be for supporters on nongame days,” he said. It is 38 or 40 degrees Celsius in June, he said, or more than 100 degrees Fahrenheit. “It is impossible to do anything on the street.”

Even the Qataris believed his verdict was a crushing blow. One official who worked on Qatar’s bid admitted the evaluation report was “embarrassing”.

The more Mayne-Nicholls talked to the various administrators and plutocrats on the FIFA board, though, the more he was struck by how little his presentation had done to diminish support for Qatar among the men who held votes. Only one, he said, had asked to see the full reports. Most seemed to have made up their minds.

“They were telling me that the Qataris were coming really strongly,” he said. “They were the ones that voted. I immediately realized that Qatar would win.”

He was not the only one. On the eve of the vote, a consultant with Qatar’s bid recalled turning to a senior Qatari bid official and asking how things looked. He was shocked by the certainty of the response: “It’s done.”

He was right. Even before Blatter opened the envelope to confirm that the Middle East would host the World Cup for the first time, Al-Jazeera, the news network based in Doha, had broadcast news of Qatar’s victory.

The fallout, though, was just beginning. Two members of the committee had not even been permitted to vote, having been suspended after being recorded by undercover reporters trying to sell their ballots.

More accusations of corruption and bribery followed. The US Department of Justice accused three South American voters of accepting seven-figure bribes to select Qatar. Within a few years, in fact, almost every one of the 22 members of the committee who had participated in the vote had been accused of or charged with corruption. Dozens of other executives had been arrested. Most were forced out of FIFA, and several were barred from soccer altogether.

Even those at the very top of the rotten pyramid had not escaped. Blatter grudgingly announced he would resign, then was banned anyway. Platini was forced out, too, over an unrelated ethics charge that led to a fraud trial in Switzerland. (He and Blatter were both acquitted.) For a while, it seemed as if FIFA itself might not survive a decision of its own making.

Building on Sand

Qatar’s leaders had been expecting the questions.

As the country fine-tuned its bid for the World Cup, its representatives spent hours in media training sessions with public-relations consultants drafted in from Europe, trying to craft responses to potentially awkward inquiries about the country’s treatment of migrant workers and its attitude toward gay rights.

It was uneasy ground for even the most senior officials, given that homosexuality was, and is, illegal in Qatar. In one media training session viewed by The New York Times, Sheikh Mohammed, the youngest son of the country’s ruler at the time, replied to a mock question on the subject by insisting that all visitors to the country would be welcomed.

When a media trainer responded by pointing out that a journalist might follow up by asking how that can be squared with laws that criminalize homosexuality, the prince responded, “It’s illegal in most countries.” Uncertain, his eyes darted from side to side. “Isn’t it?”

Confronted at a different point about the country’s treatment of migrant workers, he insisted that Qatar “has already taken the necessary steps” to protect them. “Everybody respects the migrant workers here,” he said.

As it turned out, all the preparation was in vain. The questions never came. Instead, the news media’s focus during the bidding was on the country’s size, its searing summer temperatures and — largely — if beer would be available in the Muslim nation during the tournament.

“I sat in on so many interviews, and nobody would ask,” said Phaedra al-Majid, a former media adviser to the bid who later accused Qatar of breaking ethical rules to secure the tournament. It hardly mattered. “No one believed Qatar was going to win.”

It was only after it had secured the tournament that the difficult questions came. And they have not stopped.

Qatar’s vision for the World Cup did not just require the building of seven stadiums and the refurbishment of an eighth. The country also needed an entire network of roads and rails to transport fans between the arenas and dozens upon dozens of hotels to house them — nothing less than an entirely redrawn country, rising from the sand in a $220 billion nation-building project.

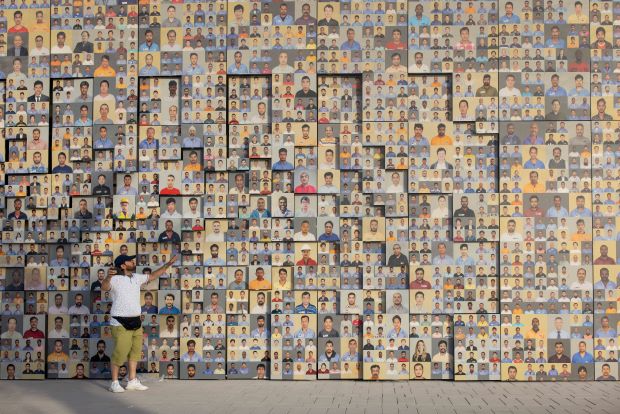

To achieve it, Qatar recruited hundreds of thousands of migrant workers from some of the poorest corners of the planet, swelling the country’s population — which grew by 13.2% in the last year alone — and drawing intense focus on the labourers’ treatment, their rights and their living conditions.

How many have died over the last decade or more is not known, and may never be. Many thousands more have returned home sick or injured or deprived of the pay they were promised.

“This event was entirely built on the backs of migrant workers, on a completely unequal balance of power,” said Michael Page, deputy director in the Middle East and North Africa division at Human Rights Watch. “These were very predictable abuses.”

Though Qatar has now — at FIFA’s behest — halted most construction projects and sent home most of the workers before the World Cup starts, it remains reliant on imported labour: Security professionals from Turkey, Pakistan, Egypt and France, among other countries, have been imported to bolster an overmatched local police force. A new wave of migrant workers has arrived, meanwhile, to staff the hotels, man the stadiums and serve the food.

The country’s small size, though, has done nothing to contain its ambition. This summer, for example, Qatar announced that as part of the World Cup it would hold a dance music festival at Ras Abu Fontas, just south of Doha, featuring a fire-breathing, laser-shooting spider borrowed from the Glastonbury music festival in England.

“In the few months before a tournament, most countries are scaling down,” said Ronan Evain, a director of Football Supporters Europe. “Qatar has just kept scaling up.”

The aim, organizers say, is to ensure an unparalleled fan experience. It will certainly be a different one: Qatar shocked FIFA and fans alike on Friday (18) by deciding, only days before the tournament’s opening match, to go back on its promise to allow the sale of beer at its eight World Cup stadiums. It will still be available in certain World Cup areas, including for several dedicated hours a day in fan zones, but there was no denying Friday that the hosts had, belatedly, reset the tournament’s traditions to satisfy local rules.

The about-face raised new questions about whether everyone — particularly LGBTQ+ fans — will face the kind of welcome that Qatar’s organizing committee and FIFA have consistently guaranteed.

This month, Khalid Salman, a former Qatari national team player now deployed as an ambassador for the World Cup, did not seem to have heard the organizers’ messaging. “Homosexuality is haram here,” he told a German documentary, using an Arabic word that roughly translates as forbidden. “It is haram because it is damage in the mind.”

Game Changer

Javier Tebas was furious. The outspoken president of Spain’s top league had arrived in Doha along with representatives from the most powerful bodies in soccer: FIFA; the rest of the game’s major leagues; and the European Club Association, an organization that represents the interests of the teams themselves.

Their task was to answer a question that nobody had ever needed to ask: When, exactly, should the World Cup be held?

In the run-up to the vote in Zurich, and for several years afterward, Qatar had insisted there was no reason the tournament could not be held in its traditional window in the European summer. The searing Gulf heat, the organizers insisted, would not be a problem, because of plans to outfit each stadium with the air-conditioning system that had impressed Mayne-Nicholls and his team.

By 2013, though, the mood had changed. A FIFA task force was established to examine the feasibility of moving the World Cup. In early 2015 it reported back, recommending shifting the competition to November and December, directly in the middle of the European season that drives much of the interest, and the money, in the game.

As he arrived in Doha for talks on the topic that year, Tebas assumed the battle lines were drawn: The leagues and the clubs “were against the dates” FIFA was proposing, Tebas said. That unanimity did not last, though. The clubs acquiesced after FIFA increased the payments they would get for releasing players for the tournament. Tebas recalled banging his hands on the table in frustration when he was told. “It was all for show,” he said. “It felt like we were being tricked.”

In many ways, though, Europe’s unwanted hiatus is the least of the consequences of FIFA’s decision to hand Qatar the World Cup. A brief interruption to a single season, after all, is far less significant than a years-long shift in the game’s landscape.

It was not only the fate of the World Cup that was under discussion at that meeting of Platini, Sarkozy and the Qatari delegation at the Élysée Palace in November 2010. So, too, was the future of Paris St.-Germain, the club Sarkozy supported. (Its president at the time, Sébastien Bazin, was also present in Sarkozy’s office that day.) Qatar wanted not only to buy the team, but to establish a sports broadcaster to show its games, and to bankroll the rest of French soccer. Less than a year later, it was doing just that.

Backed by Qatar Sports Investments’ seemingly bottomless funds, PSG began a lavish spending spree that no domestic rival could even consider, acquiring star after star as it looked to overtake Europe’s traditional powers. The moves, individually and in the aggregate, would have a profound and lasting impact on European soccer.

In the summer of 2017, PSG flexed its financial muscles in the boldest way yet: It signed Neymar, the Brazilian forward, from Barcelona at a cost of $222 million, doubling the previous world transfer record, and then a few weeks later added the French striker Kylian Mbappé for $180 million more. The two deals, at a stroke, shifted the global transfer market for good.

But Qatar was not finished. Its television network, beIN Sports, soon became the most voracious collector of sports media rights in the world, part of an expansion to Europe that was also agreed at the Élysée meeting. BeIN’s powerful chief executive, Nasser al-Khelaifi, is also the president of PSG.

He also has a seat on the board of European soccer’s governing body, UEFA, and last year he became head of the European Club Association as well. He inherited that post in the aftermath of the abortive start of the European Super League, a supposed alternative to the Champions League concocted by several of the most famous clubs in soccer.

Executives involved with the plan claimed their rationale was to save the sport; in reality, at least a part of the motivation was to try to clip the wings of PSG and Manchester City, the deep-pocketed English team owned by a group closely linked to the ruling family of Abu Dhabi. The two clubs’ spending, their rivals said, has distorted soccer beyond recognition, placing any club that tried to keep pace at risk of implosion.

For evidence of that, they need point to the only team that tried. Barcelona, stung by the loss of Neymar, quickly found itself trapped in an inflationary spiral. By 2021, its financial distress was such that it could no longer afford the contract of Lionel Messi, the finest player in its history. He bade farewell to the only club he had known in a tear-stained news conference. A few minutes later, he was photographed at an airport in Barcelona. His destination, of course, was PSG.

The Show Must Go On

A few weeks before the World Cup, Gianni Infantino, Blatter’s successor as FIFA president, wrote to each of the 32 nations that had qualified for the tournament. Now a resident of Qatar, Infantino urged all of them “not to let football be dragged into every ideological or political battle that exists.”

It was time, he said, to let the sport “take the stage”.

It may be too late for that. As the tournament neared, the criticism of FIFA’s decision to take it to Qatar only grew more pointed. An expanding list of current players, former players, coaches, sportswear manufacturers and, in particular, fans have been vocal in their opposition. The captains of England and Wales have agreed to wear a special armband promoting gay rights. Blatter, as recently as this month, admitted the choice of Qatar was a “mistake”.

Qatar’s response, in turn, has been to become steadily more indignant. The country’s emir — present, as crown prince, at the meeting at the Elysée with Platini — lashed out last month at what he described as an “unprecedented” campaign of criticism from the West. Qatar’s foreign minister, two weeks ago, labelled the questions over its suitability to host the tournament “very racist”.

FIFA has not always been so opposed to the idea of using soccer for ideological purposes. Even after all of the investigations, the warrants and the arrests, FIFA as an institution has always justified its decision to go to Qatar by insisting that the sport can be an agent for progress.

As the tournament that the host country was willing to pay almost any price to obtain gets underway, though, and as the eyes of the world turn to a tiny corner of the Gulf, it is hard not to feel it is the other way around: Soccer may or may not change Qatar, but Qatar has changed soccer forever.

-New York Times

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.