At Afghan universities, increasing fear that women will never be allowed back

By Cora Engelbrecht and Sharif Hassan

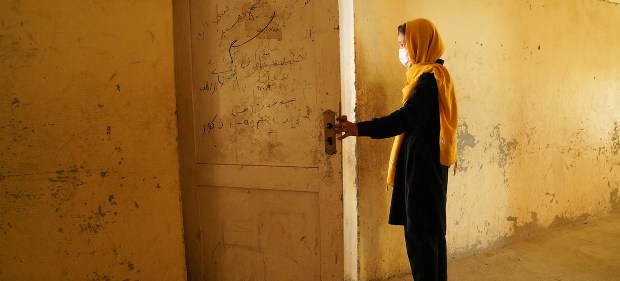

KABUL – Women who are instructors and students at Afghanistan’s public universities increasingly fear that the Taliban will never let them go back to their classes, and professors are quitting or trying to leave the country in droves.

According to estimates by lecturers who spoke with The New York Times, more than half of the country’s professors have either left their jobs or say they will. Kabul University, the country’s premier public college, has been particularly hard-hit, losing a quarter of its faculty in recent days, one of the university’s board members said.

A former member of the faculty described a deeply fearful environment. “Kabul University is facing a brain drain,” said Sami Mahdi, a journalist and former lecturer at the university’s School of Public Policy, who spoke over the phone from Ankara, Turkey. He flew out of the country the day before Kabul fell to the Taliban, he said, but has kept in touch with his students back home. “They are disheartened — especially the girls, because they know that they won’t be able to go back.”

The Taliban’s return to power in August immediately sent chills through the country’s higher education system, which over the past two decades had emphasized the improved educational opportunity for women and had been buoyed by hundreds of millions of dollars in foreign aid.

Many feared that the group would return to its harsh policies from its first time in power in the 1990s, when women were only allowed in public if accompanied by a male relative and would be beaten for disobeying, and were kept from school entirely.

In recent weeks, Taliban officials went to pains to insist that this time would be better for women, who would be allowed to study, work and even participate in government.

But none of that has happened. Taliban leaders recently named an all-male Cabinet. The new government has also prohibited most women from returning to the workplace, citing security concerns, though officials have described that as temporary. (The original Taliban movement did that as well in its early days in 1990s, but never followed up.)

Then, two weeks ago, the Taliban began replacing the leadership at Afghanistan’s major universities. Their choice at Kabul University raised particular outrage: The new chancellor was Mohammad Ashraf Ghairat, a 34-year-old devotee of the movement who was widely criticized in academic circles and on social media as being unqualified and holding troubling views on women’s rights.

In a symbolic act of resistance, the teachers union of Afghanistan sent a letter last week to the government demanding that it rescind Ghairat’s appointment.

That outrage intensified Monday (Sept 27), when a post on a Twitter account saying it was Ghairat’s official outlet said that women would not be allowed to return to Kabul University until a “real Islamic environment” could be established. (The Times was unable to verify that the account was run by the chancellor or a representative from his office.)

That statement echoed earlier ones by the Taliban leadership that women would eventually be allowed back to classes only after a secure and Islamic environment had been established, including segregated classes.

Some female staff members, who have worked in relative freedom over the past two decades, have pushed back, questioning the idea that the Taliban had a monopoly on defining the Islamic faith and fearing that the group’s real intent was to perpetually keep women away from education, as it did in the ’90s.

“In this holy place, there was nothing un-Islamic,” one female lecturer said, speaking on condition of anonymity out of fear of reprisal, as did several others interviewed by The New York Times. “Presidents, teachers, engineers and even mullahs are trained here and gifted to society,” she said. “Kabul University is the home to the nation of Afghanistan.”

After the Twitter post, multiple calls to reach the chancellor’s office and top aide for confirmation were rejected, with the aide saying that Ghairat would not speak to the press and referring journalists to a senior Taliban spokesman.

Reached for comment, the Taliban’s chief spokesman, Zabihullah Mujahid, described the Twitter post as perhaps being Ghairat’s “own personal view.” But he did not give any assurances that women would be able to attend work or classes at universities, saying that the Taliban were still working to devise a “safer transportation system and an environment where female students are protected.”

Among the Afghan academic community, few believe that women will be allowed to return to higher education in serious numbers.

While some women have returned to class at private universities, the country’s public universities, which had been scheduled to start their academic year this week, remain closed to everyone, not just women. Even if they reopen, it appears that women will be required to attend segregated classes, with only women as instructors. But with so few female teachers available — and many of them still publicly restricted from working — many women will almost certainly have no classes to attend.

During the country’s civil war in the early 1990s, university activity was limited. When the Taliban took power, in 1996, they brought the civil war mostly to an end but did little to revive their higher education system. Women and girls were prohibited from attending school altogether.

Following the American invasion in 2001, the United States poured more than $1 billion into expanding and strengthening Afghanistan’s colleges and universities. US allies, as well as international institutions like the World Bank, spent heavily as well. By 2021, there were more than 150 institutions of higher education, which educated nearly a half million students — approximately a third of whom were women.

Now, all of that development is in doubt, with the future of the higher education system up in the air. Tens of thousands of public university students are staying home because their schools are closed. The American University in Afghanistan, in which the US invested over $100 million, has been abandoned completely and taken over by the Taliban.

Professors and lecturers from across the country, many of whom were educated overseas, have fled their posts in anticipation of more stringent regulations from the Taliban. In their wake, the government is appointing religious purists like Ghairat, many of whom have minimal academic experience, to head the institutions.

Foreign aid for higher education came to an abrupt halt after the Taliban takeover in August. Money from the United States and its NATO allies ended, as did funding from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. That effectively deprived thousands of government workers and teachers of their salaries.

The exodus of intellectual capital is not limited to Kabul University. At the University of Herat, in western Afghanistan, only six out of 15 professors remain in the journalism faculty. Three who fled are hoping to enter the United States from other countries; and six of the absent lecturers were studying abroad before the Taliban returned to power and say that they won’t return. Similar concerns have been reported at Balkh University, in northern Afghanistan, as well. The Taliban replaced school leadership at all those institutions.

-New York Times