Sri Lanka adoption: The babies who were given away

By Saroj Pathirana

Thousands of Sri Lankan babies were put up for adoption between the 1960s and 1980s – some of them sold by ‘baby farms’ to prospective parents across Europe. The Netherlands, which accepted many of those infants, has recently suspended international adoptions following historical allegations of coercion and bribery. As that investigation unfolds, families who never stopped thinking about the children who vanished hope they will be reunited.

Indika Waduge remembers the red car driving off with his mother and sister, Nilanthi, inside. He and his other sister Damayanthi stayed at home and waited for their mother to return. When she came back the next day, she was alone.

“When we said goodbye to each other I never thought Nilanthi was about to go abroad or it was the last time we’d see each other,” he says.

This was in either 1985 or 1986, when Indika’s father had left his mother, Panikkarge Somawathie to raise three children alone. As the family struggled to survive, he remembers a man his mother knew convincing her to give Nilanthi, who was four or five, up for adoption.

Indika says this man was a broker for a ‘baby farm’ in a suburb of the capital, Colombo, called Kotahena. He claims that while a female clerical officer at a court and her husband ran it, it was the broker who arranged the adoption for foreign parents – mainly Dutch couples.

Somawathie knew it was a centre that arranged babies for adoption as a business, says her son. But at the time, she felt she had no choice. She was paid about 1,500 Sri Lankan rupees (approximately $55 at the time).

“She did it because she couldn’t feed all three of us,” Indika says. “I don’t blame her.”

Indika remembers visiting the baby farm with both his parents before Nilanthi was given away, although he cannot recall why. He describes a two-storey house where several mothers with babies were sleeping on mats on the floor.

“It was a dirty slum, it was like a hospital hall,” he says. “I now understand that it was a baby farm. They would look after the mothers until they give birth and then sell the babies. They were doing a profitable business there.”

A few years later, during the uprising of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP -People’s Liberation Front) against the State, some 60,000 people were killed. Indika says one of them was the baby farm broker, who was burnt to death in his car – it was “all over the media”, he says, and when he saw the picture of the vehicle, he knew it was the same one that had driven off with his sister.

Indika, 42, says his mother is unwell and he is desperately trying to find Nilanthi, who he believes went to live in either the Netherlands or Austria, but he doesn’t even have a single photograph of her.

“My mother is 63. Her only hope is to see my sister before she dies. So I’m doing this to fulfil my mother’s wish.”

It is a desire shared by many mothers who felt they had to give their children away.

Ranaweera Arachchilage Yasawathi insists she had no intention of selling her baby, but she did because of the social taboo of being a single unmarried mother.

“It was the best decision I could take at the moment, but it was a very painful thing,” she says. “I was not thinking about myself but about my baby. I was not in a position to look after him. And I was afraid of the reaction from society.”

Sri Lanka is a conservative society made up of mostly Sinhalese and Buddhist nationals. Sex before marriage was then, and still is, a huge taboo and abortions are illegal.

Yasawathi became pregnant at 17 by an older man she fell in love with while walking to school in 1983. Despite her older brothers disapproving of the relationship, she moved into her boyfriend’s family home, although she says she “wasn’t that keen to go – I was very young and vulnerable”.

To begin with, he was nice to her, she said, but his behaviour changed. She learned he was having other relationships. After six or seven months, he took her back to her family’s home and vanished. When her brothers and sister learned she was two months pregnant, they threw her out.

Desperate, Yasawathi approached a local female marriage registrar for help. When it was time to give birth, the registrar introduced her to a hospital attendant in the city of Ratnapura who arranged the adoption of her son, Jagath Rathnayaka. He was born on December 24, 1984.

“Nobody was there to look after me when I gave birth. I was in the hospital for about two weeks and then I was taken to a place like an orphanage in Colombo. I don’t remember the details or where exactly it was, but there were four or five others like me there,” she says.

“It was there a white couple took my son for adoption but I didn’t know where they were from. I was given 2,000 Sri Lankan rupees (approximately $85 in 1983) and a bag of clothes to take home. That’s all I received.

“I suffered a lot. I even tried to take my own life.”

A few months later, she received a letter from a couple in Amsterdam containing a picture of her son.

“I don’t read or speak English. Somebody who knows the language told me that it said my son was doing well. The adoptive parents also expressed gratitude for giving them my child. I have never received any information about my son since.”

Yasawathi, who lives in the rural town of Godakawela, later married and had another son and two daughters. The 56-year-old says not knowing where her first son is has left a void in her heart. But even now, she remains worried that finding him would cause a backlash in Sri Lankan society.

“Whenever I see a white lady I feel like asking her whether she knows anything about my son. I am very helpless today,” she says, her voice breaking. “I hope nobody ever should experience what happened to me. My only wish is to see my first son before I die.”

In 2017, the Sri Lankan health minister admitted on a Dutch current affairs program that thousands of babies had been fraudulently sold for adoption abroad in the 1980s.

Up to 11,000 children may have been sold to European families, with both parties being given fake documents. About 4,000 children are thought to have ended up with families in the Netherlands, with others going to other European countries such as Sweden, Denmark, Germany and the UK.

Some were reportedly born into ‘baby farms’ that sold children to the West – leading to a temporary ban by the Sri Lankan authorities in 1987 on foreign adoptions.

Tharidi Fonseka, who has researched the adoptions for more than 15 years, says there were indications some influential and powerful people might have cashed in on the predicaments of desperate women.

Hospital workers, lawyers and probation officers all profited, according to Andrew Silva, a tourist guide in Sri Lanka who has helped reunite about 165 adopted children with their biological mothers.

He started to help people in 2000 after a Dutch national donated some kits to the football team he played for. They became friends and the Dutch man asked Andrew whether he could help some of his friends in the Netherlands find their birth mothers. Since then, Andrew has also been approached by Sri Lankan mothers.

“I heard from some mothers that certain hospital workers were involved in selling those babies,” he says. “They were looking for vulnerable, young mothers and offered their ‘help’ to find a better home for their babies.

“Some mothers told me that some lawyers and court officials kept babies in certain places until one of them could act as a magistrate to issue the adoption orders.”

The idea that influential people were involved in the adoption ring is not uncommon in these women’s stories.

When Kariyapperuma Athukorale Don Sumithra became pregnant with her third child in 1981, she and her husband knew they could not keep her and turned to a local pastor in Colombo.

She says he arranged the adoption of their baby, who was born in November, and gave them 50,000 Sri Lankan rupees (approximately $2,600 at the time). But they were not given any documents.

“We didn’t have anywhere to live and no particular income. Together we decided to give our daughter away, she was about two or three weeks old,” says Sumithra.

“When I asked the pastor he always said, ‘don’t worry, your child is fine,’ but I don’t know anything about her.”

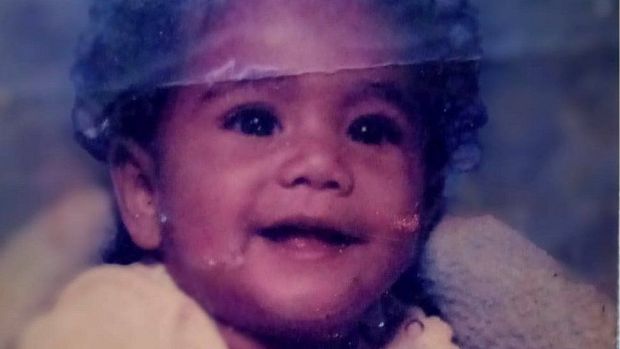

Sumithra had another son afterwards but says thinking about her daughter causes her constant pain. The 65-year-old, who lives in Kaduwela, desperately wants to find her child, but she lost the only photos she had of her in a flood and she no longer has contact details for the pastor.

“My second daughter tells me, ‘Let’s go and find that pastor’. My only request is please help me find my daughter.”

Andrew Silva has tried to help Sumithra, but so far his efforts have failed. He says his search is often hampered by the fact women were given forged documents and false details.

The adopted children often find it just as hard to trace their biological families and even if they are successful, the outcome can be heartbreaking.

The first time Nimal Samantha Van Oort visited Sri Lanka in 2001, he met a man from a travel agency who offered to help find the mother who gave him and his twin brother up for adoption at six weeks old in 1984.

It wasn’t until 2003 that he received a phone call from the man saying he had found the birth family but it wasn’t good news – the twins’ mother had died in 1986, aged 21, three months after giving birth to a daughter.

“It was the darkest day of my life, and my brother’s,” says Nimal Samantha. “I always wanted to find out how she was and the reason why she gave me away because she was the woman who gave me my life.

“The most important thing was for me to find out whether she was doing well.”

Nimal Samantha later helped set up a non-profit called the Nona Foundation – named after his mother – with a group of Sri Lankan adoptees. It has so far helped 1,600 girls who are victims of sexual violence and human trafficking in Sri Lanka by funding orphanages, housing victims and paying for education and training.

In September, Nimal Samantha was knighted for his work by the king of the Netherlands during a surprise visit from a royal representative at a foundation board meeting.

“It was a shock but a big honour and very nice recognition,” he says.

Nimal Samantha believes the Dutch government’s decision to ban all adoptions from abroad is “not the best solution”.

However, officials have warned the Netherlands’ adoption system is still susceptible to fraud following a two year investigation which highlighted “serious violations” in the process of adopting children from countries including Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Brazil and Colombia from 1967 to 1997.

Though the fraudulent and secretive nature of many of the adoptions has often made tracing relatives difficult, there have been some happy reunions.

Sanul Wilmer was born in Colombo on February 27, 1984. He stayed with his mother at an orphanage in Dehiwala before he was adopted at ten weeks old.

“I knew I was an adopted child from the childhood. So I always wanted to meet my biological parents,” he says.

“I always felt this identity crisis within me – who am I? I am a Sri Lankan by the look, but a Dutch due to my upbringing. I was always curious about my origins.”

He began writing to his adoption agency in the Netherlands for help tracing his biological family when he was eight. He finally got a reply at 15 and the agency was able to trace his mother, who he met the following year.

“I found out I had a sister and a brother and that my father was still with my mother. We all went to visit my family in Horana, which was very exciting, emotional and sad at the same time,” he says.

“I was happy to meet them but I was sad that I couldn’t talk to them as I didn’t speak Sinhala and they didn’t understand English. I felt sorry I had such a different life from theirs.”

The 37-year-old, who is a physician associate at the University Medical Centre of Utrecht in Amsterdam, is now a Sinhala language teacher for adopted children like himself.

He says his mother told him why she had given him away, but he does not want to reveal the reason for fear of hurting her. Sanul says he holds no ill-will towards her and regularly visits her in Sri Lanka, while she and his younger brother also attended Sanul’s wedding in Amsterdam in 2019.

“I’m a happy man because I found out that I have a brother and sister,” he says.

The Dutch government revealed in February that its officials were aware of wrongdoing for years and had failed to intervene. It recently said a future cabinet would have to decide how to proceed with overseas adoptions.

Sri Lanka’s co-cabinet spokesman, Minister Keheliya Rambukwella, told the BBC that the illegal adoptions that took place in Sri Lanka during the late 1980s were “mixed together with tourism”.

He said he would raise the Dutch government’s decision at the next cabinet meeting, adding: “Currently the issue is not that bad, but I wouldn’t say it is not happening now.”

-BBC World Service