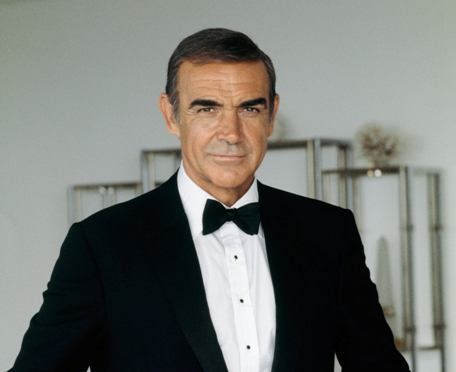

Sean Connery, who embodied James Bond and more, dies at 90

By Aljean Harmetz

Sean Connery, the irascible Scot from the slums of Edinburgh who found international fame as Hollywood’s original James Bond, dismayed his fans by walking away from the Bond franchise and went on to have a long and fruitful career as a respected actor and an always bankable star, died on Saturday (31). He was 90.

His death was confirmed by Nicola Sturgeon, Scotland’s first minister, on Twitter. “Our nation today mourns one of her best loved sons,” she wrote.

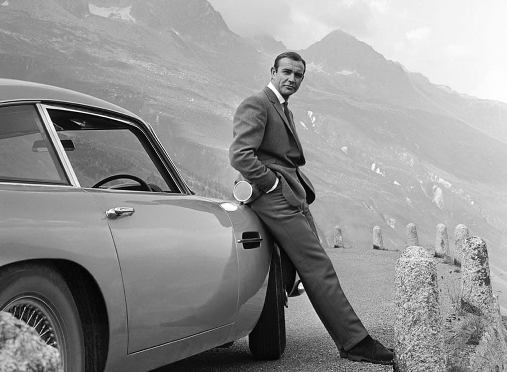

“Bond, James Bond” was the character’s familiar self-introduction, and to legions of fans who have watched a parade of actors play the role — otherwise known as Agent 007 on Her Majesty’s Secret Service — none uttered the words or played the part as magnetically or as indelibly as Connery.

Tall, dark and dashing, he embodied the novelist Ian Fleming’s suave and resourceful secret agent in the first five Bond films and seven overall, vanquishing diabolical villains and voluptuous women alike beginning with ‘Dr. No’ in 1962.

As a more violent, moody and dangerous man than the James Bond in Fleming’ books, Connery was the top box-office star in both Britain and the United States in 1965 after the success of ‘From Russia With Love’ (1964), ‘Goldfinger’ (1964) and ‘Thunderball’ (1965). But he grew tired of playing Bond after the fifth film in the series, ‘You Only Live Twice’ (1967), and was replaced by George Lazenby, a little-known Australian actor and model, in ‘On Her Majesty’s Secret Service’ (1969).

Connery was lured back for one more Bond movie, ‘Diamonds Are Forever’ (1971), only by the offer of $1 million as an advance against 12% of the movie’s gross revenues. Roger Moore took over for ‘Live and Let Die’ (1973) and continued to play the part for another 12 years. George Lazenby’s career never took off.

Connery would revisit the character one more time a decade later, in the elegiac ‘Never Say Never Again’ (1983), in which he wittily played a rueful Bond feeling the anxieties of middle age. But he had made clear long before then that he was not going to let himself be typecast.

He searched out roles that allowed him to stretch as an actor even during his Bond years, among them a widower obsessed with a woman who is a compulsive thief in Alfred Hitchcock’s ‘Marnie’ (1964) and a raging, amoral poet in the satire ‘A Fine Madness’ (1966). His first post-Bond performance was as a burned-out London police detective who beats a suspect to death in ‘The Offence’ (1972), the third of five movies he made for the celebrated director Sidney Lumet. (The others were ‘The Hill’ in 1965, ‘The Anderson Tapes’ in 1971, ‘Murder on the Orient Express’ in 1974 and ‘Family Business’ in 1989.)

“Nonprofessionals just didn’t realize what superb high-comedy acting that Bond role was,” Lumet once said. “It was like what they used to say about Cary Grant. ‘Oh,’ they’d say, ‘he’s just got charm.’ Well, first of all, charm is actually not all that easy a quality to come by. And what they overlooked in both Cary Grant and Sean was their enormous skill.”

In the 1970s and ’80s, Connery gracefully transformed himself into one of the grand old men of the movies. If his trained killer in the futuristic fantasy ‘Zardoz’ (1974), his Barbary pirate in ‘The Wind and the Lion’ (1975) or his middle-aged Robin Hood in ‘Robin and Marian’ (1976) did not erase the memory of his James Bond, they certainly blurred the image.

Connery won a best-actor award from the British Academy of Film and Television Arts for ‘The Name of the Rose’ (1986), in which he played a crime-solving medieval monk, and the Academy Award as best supporting actor for his performance as an honest cop on the corrupt Chicago police force in ‘The Untouchables’ (1987). Connery taught himself to understand that character — Jim Malone, a cynical, streetwise police officer whose only goal is to be alive at the end of his shift — by noting the other characters’ attitudes toward him.

After reading Malone’s scenes, he told The New York Times in 1987, he read the scenes in which his character did not appear. “That way,” he said, “I get to know what the character is aware of and, more importantly, what he is not aware of. The trap that bad actors fall into is playing information they don’t have.”

Even before his acting ability was apparent, the 6-foot-2 Connery had a remarkable physical presence, onscreen and off. Lana Turner picked him to play the war correspondent with whom she tumbles into bed in the forgettable 1958 melodrama ‘Another Time, Another Place’. He earned his chance as Bond when the producers Albert Broccoli and Harry Saltzman watched him walk.

“We signed him without a screen test,” Saltzman said.

Connery’s magnetism did not fade as he grew older. In 1989, when he was 59 years old and had long since discarded his James Bond toupee, People magazine anointed him the ‘Sexiest Man Alive’. His response was to growl that not many men are sexy when they’re dead.

‘The Man Who Would Be King’ (1975), directed by John Huston, in which Connery played a British soldier who sets out to loot a country and is mistaken for a god, was among the highlights of his second act. When Huston had first tried to finance a movie based on Rudyard Kipling’s short story of the same name 20 years earlier, he intended the role of Danny Dravot, the exuberant rogue who fatally begins to believe in his own grandeur, for Clark Gable, the undisputed king of Hollywood during the 1930s and ’40s. (The role of his companion Peachy Carnehan, played by Michael Caine, was originally intended for Humphrey Bogart.) Connery was, Pauline Kael of The New Yorker wrote, “a far better Danny than Gable would ever have been.”

She continued: “With the glorious exceptions of Brando and Olivier, there’s no screen actor I’d rather watch than Sean Connery. His vitality may make him the most richly masculine of all English-speaking actors.” Few actors, she added, “are as un-self-consciously silly as Connery is willing to be — as he enjoys being.”

If he enjoyed being silly on the screen, Connery was darker and more complex when the arc lights were turned off. Always afraid of being cheated, he audited the books of almost all of his movies and sued anyone he thought was taking advantage of him, from his business manager to the producers of the Bond films.

In 1978 Connery and Caine filed suit against Allied Artists, the distributor of ‘The Man Who Would Be King’, over the way their share of the movie’s receipts was calculated. (The case was settled out of court.) He was still at it in 2002, suing the producer Peter Guber and Mandalay Pictures for backing out of ‘End Game’, a CIA thriller in which Connery was to star. (He later dropped the suit.)

The smouldering resentment that fuelled his many lawsuits, which he carried with him from his childhood, was also one of the keys to his success as an actor.

He was born Thomas Sean Connery on Aug. 25, 1930, and his crib was the bottom drawer of a dresser in a cold-water flat next door to a brewery. The two toilets in the hall were shared with three other families. His father, Joe, earned two pounds a week in a rubber factory. His mother, Effie, occasionally got work as a cleaning woman.

At the age of 9, Thomas found an early-morning job delivering milk in a horse cart for four hours before he went to school. His brother, Neil, had been born in December 1938, and the usual meals of porridge and potatoes had to be stretched four ways. Once a week, if the family had a sixpence to spare, Thomas would walk to the public baths and swim “just to get clean”.

Like the months that 12-year-old Charles Dickens spent working in a factory that made shoe blacking, Connery’s deprived childhood informed the rest of his life. When he was 63, he told an interviewer that a bath was still “something special”.

His anger was never far below the surface. What he called his “violent side”, he told The Times, may have been “ammunitioned” by his childhood. The same was true of his odd combination of penury and generosity.

A passionate golfer — he discovered the game about the same time he discovered James Bond — he was the only player at the Bel-Air Country Club in Los Angeles who carried his own bag rather than pay a caddy to carry his clubs for him. Yet he gave the $1 million he earned on ‘Diamonds Are Forever’ to the Scottish International Education Trust, an organization he founded to help poor Scots get an education.

When asked why he was willing to take second billing as a coal miner saboteur to Richard Harris’ company spy in ‘The Molly Maguires’ (1970), he said, “They paid me a million dollars for it, and, for that kind of money, they can put a mule ahead of me.” But he donated 50,000 pounds to England’s National Youth Theatre after he read that the theatre needed money. An ardent supporter of Scottish nationalism, he also gave 5,000 pounds a month to the Scottish National Party.

As a national referendum on independence approached in 2014, Connery wrote an opinion article for The New Statesman arguing in favour it.

“As a Scot and as someone with a lifelong love for both Scotland and the arts, I believe the opportunity of independence is too good to miss,” he wrote. “Simply put — there is no more creative act than creating a new nation.” However, because his primary residence was not in Scotland, Connery was not eligible to vote.

At the age of 13, Thomas Connery became a full-time milkman. Britain had been at war for four years, and any able-bodied boy could get a job. Three years later, with the soldiers coming home and work scarcer, he joined the Royal Navy.

He signed up for 12 years, but was discharged at 19 after acquiring an ulcer. He had also acquired two tattoos on his right arm — ‘Mum and Dad’ and ‘Scotland Forever’ — and a small disability grant, which he used to learn furniture polishing. Then he went to work putting the finish on coffins. In his off hours he took up soccer (he played semi-professionally) and bodybuilding.

Bodybuilding led indirectly to acting. In 1953, he and a friend went to London to compete in the Mr. Universe contest. Connery got a minor award — third place in the tall man division, according to most accounts — but, more important, while there he heard about auditions for a touring production of the musical ‘South Pacific’. He was chosen for the chorus because he looked like a sailor and could do handstands.

During the year Connery toured in ‘South Pacific’, he lost much of a Scottish accent so impenetrable that, he later claimed, other actors at first thought he was Polish. His name was shortened to Sean Connery. And he found himself a mentor. An American actor in the cast, Robert Henderson, gave him a reading program that included all the plays of George Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde and Henrik Ibsen, along with the novels of Thomas Wolfe, Proust’s ‘Remembrance of Things Past’ and Joyce’s ‘Ulysses’.

“I spent my ‘South Pacific’ tour in every library in Britain, Ireland, Scotland and Wales,” Connery told The Houston Chronicle in 1992. “And on the nights we were dark, I’d see every play I could. But it’s the books, the reading, that can change one’s life. I’m the living evidence.”

The next few years were a blend of small stage and television roles. His lucky break came on March 31, 1957. Jack Palance was to have starred in Rod Serling’s ‘Requiem for a Heavyweight’ on live television for the BBC. Palance had triumphed in the same role the previous year on “Playhouse 90.” But he cancelled at the last minute, and Connery inherited the role of the ageing boxer Mountain McClintock. Although miscast, a reviewer for The Times of London wrote, he had “shambling and inarticulate charm.” Within 24 hours, Connery had gotten his first movie offers.

A string of B movies followed, including ‘Action of the Tiger’ (1957), a thriller starring Van Johnson in which he had a small part, and ‘Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure’ (1959), in which he played a villain out to destroy a village. He also played a private in the all-star D-Day saga ‘The Longest Day’ (1962) and a man enchanted into falling in love in Disney’s ‘Darby O’Gill and the Little People’ (1959).

“In these early films,” observed the novelist and filmmaker Michael Crichton, who directed Connery in ‘The Great Train Robbery’ (1979), “Connery exudes a rich, dark animal presence that is almost overpowering.”

His Count Vronsky opposite Claire Bloom’s Anna in a 1961 BBC television adaptation of Tolstoy’s ‘Anna Karenina’ caught the attention of the men who were about to produce ‘Dr. No’.

Both Connery and the character he played were instant sensations. “James Bond is clearly here to stay,” Variety wrote prophetically after ‘Dr. No’ opened. “He will win no Oscars but a lot of enthusiastic followers.”

Connery and Diane Cilento, an actress he had met when they played lovers in a television version of Eugene O’Neill’s ‘Anna Christie’ in 1957, were married on Nov. 30, 1962. Their son, Jason, who would grow up to become an actor, was born six weeks later.

The marriage lasted, more or less, until Connery met Micheline Roquebrune, a French artist and obsessive golfer, at a golf tournament in Morocco in 1970. She was married, he was married, and they both won medals. After their marriage in 1975, they lived in Marbella, Spain, mostly to avoid British income taxes but partly because of Marbella’s 24 golf courses.

By the time he returned to the role of James Bond in ‘Never Say Never Again’, at Roquebrune’s suggestion, Connery was in financial trouble because his former accountant had put the money he earned from the Bond films into unsecured property investments. Connery sued and won a $4.1 million judgment for negligence in 1984, but told reporters, “I don’t foresee I’ll get any money.”

Almost from the time he left James Bond behind, Connery shifted from gorgeous young man to character star. “The reason Burt Lancaster had a longer, more varied career than Kirk Douglas was that he refused to allow himself to be limited,” Connery told The Times in 1987. “He was more ready to play less romantic parts, and was more experimental in his choice of roles. And that’s the way I’ve tried to be. I don’t mind being older or looking stupid.”

Often willing to take roles in bad pictures if the money was good enough, Connery was the voice of a computer-generated dragon in ‘Dragonheart’ (1996) and a villain trying to unleash a weather catastrophe on London in the misfire film version of the cult British television series ‘The Avengers’ (1998). But he had more than his share of late-career triumphs as well.

He relished his role as Harrison Ford’s eccentric father in ‘Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade’ (1989) — even though Ford was only 12 years younger than he was. The next year he played a Russian nuclear submarine commander trying to defect to the United States in the film of Tom Clancy’s ‘Hunt for Red October’ and a hard-drinking but naïve British publisher recruited by British intelligence in post-Cold War Russia in ‘The Russia House’, based on John le Carré’s novel.

Connery’s last movie was one of his lesser ones: ‘The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen’ (2003), an unsuccessful screen adaptation of a clever comic-book series about a group of Victorian heroes.

In 2005, he told an interviewer that he was done with acting, less because of his age than because of the “idiots now making films in Hollywood.” Five years later, he told another interviewer: “I don’t think I’ll ever act again. I have so many wonderful memories, but those days are over.” Except for some voice-over work, and despite occasional talk of possible new projects, they were.

In addition to his wife and his son Jason, his survivors include a brother, Neil.

On July 5, 2000, wearing the dark green MacLeod tartan of the Highlands, Connery was knighted at the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh by Queen Elizabeth II. It was a knighthood that had been vetoed for two years by officials angry at his outspoken support for the Scottish National Party and his active role in the passage of a referendum that created the first Scottish Parliament in 300 years.

The palace is less than 1 mile from the tenement in Fountainbridge where Connery grew up. He never removed the ‘Scotland Forever’ tattoo that he placed on his arm when he was 18. Nor was he ever tempted to deny his identity or turn himself into an English gentleman, he told The Times in 1987:

“My strength as an actor, I think, is that I’ve stayed close to the core of myself.”

-New York Times