Olympics end as they began: strangely

By Motoko Rich

TOKYO — As the athletes finished marching into the stadium for the closing ceremony of the 32nd Summer Olympics on Sunday (8) night, the announcer asked for a big round of applause. But there simply weren’t enough people in the stands to make much noise. And the flashiest component of the ceremony, a formation of the five Olympic rings by tiny points of light, was invisible live in the stadium. The magic of its special effects played only on large screens and to television audiences.

And so one of the strangest Olympics in recent memory ended much as they began, with reduced cohorts of athletes waving to cameras and volunteer dancers rather than spectators, and rows of empty seats serving as reminders of a pandemic that could not be brought to heel by messaging about the healing power of the Games.

Yet perhaps more than any recent Olympics, the tournament was an athletic reality show, inviting viewers to seek respite from the frustration and tragedy of the past 18 months. The drama of competition and bouts of rousing sportsmanship offered diversion from the daily counts of coronavirus cases — the ones within the Olympic bubble and the vastly larger numbers outside of it.

Fans were riveted by Simone Biles and her decision to withdraw from most of her gymnastics events while speaking candidly about mental health issues. New sports like skateboarding and surfing made their Olympic debuts.

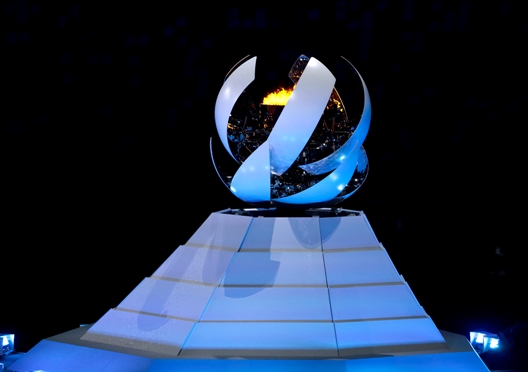

There were upsets: The US women’s soccer team fell to Canada in a semifinal; Jun Mizutani and Mima Ito won Japan’s first gold medal in table tennis over the Chinese world champions. Naomi Osaka, after lighting the Olympic cauldron for Japan, was eliminated in the third round of the women’s tennis tournament, denying the host country a potential gold medal moment it had dearly hoped for.

There were history-making triumphs: Allyson Felix surpassed Carl Lewis as the most decorated American Olympian in track and field, and Eliud Kipchoge of Kenya defended his gold medal in the men’s marathon.

And who could resist British diver Tom Daley, who was constantly spotted knitting in the stands?

Outside the stadium before the ceremony on Sunday, Ryogo Saita, 45, who was walking with his 7-year-old son, said they had enjoyed watching on television as Yuto Horigome captured skateboarding’s first gold medal for Japan. Still, with daily coronavirus infections more than doubling in Tokyo since the Games started, Saita said he was concerned. “But people also enjoy the sports,” he said. “I think it’s a good thing that they happened. It’s like I’m battling two emotions.”

Although organizers argued that the Japanese public and international audiences had embraced the Olympics after months of controversy, the numbers from NBCUniversal in the United States, the largest broadcaster at the Games, showed steep drops from the Rio de Janeiro Olympics in 2016. In Japan, a smaller proportion of viewers watched the Games than when Tokyo last hosted the event, in 1964.

Given numerous scandals involving Tokyo 2020 officials and concerns before the Games that they might result in a superspreader event, Tokyo organizers could claim success simply because the worst-case scenario did not occur. Experts, however, debated whether the Olympics normalized behaviors that helped spur a new wave of infections across the city.

Many of the performances in the closing ceremony elicited a lighthearted joy that the more somber opening ceremony did not. In one segment, actors and dancers dressed in street fashion frolicked around the center of the stadium, meant to evoke a park, with Capoeira dancers, stunt bikers, jugglers and double Dutch jumpers, a poignant demonstration of a side of Tokyo that most Olympic visitors never got to see.

In his concluding remarks, Thomas Bach, the president of the International Olympic Committee, thanked the people of Japan and noted that no organizing committee had ever had to put on a postponed Games before. “We did it — together!” he said, to lukewarm applause.

The closing festivities, based on the theme ‘Moving Forward: Worlds We Share’, was the last chance for the organizers to stage a spectacle intended to keep everyone on message about an event — and an entire movement — that had started to show cracks before the Games even began.

Politics, which the IOC assiduously insists have nothing to do with the Games, intruded in Tokyo. Kristina Timanovskaya, a Belarusian sprinter who sought protection as her country tried to force her home after she criticized her coaches, was granted asylum in Poland. The IOC took five days to strip the Olympic credentials of the coaches involved in the attempt to send her back to Belarus.

More broadly, the committee’s decision-making came under close scrutiny in Tokyo. Even before the pandemic, organizers pushed to stage the Tokyo Games during its most brutally hot weeks in order to maximize broadcasting revenues. That decision had clear repercussions, with a tennis player leaving the court in a wheelchair and events in soccer and athletics being rescheduled at the last minute. The fact that the Games went ahead during the pandemic despite strong public opposition in Japan showed the undemocratic principles that underpin the organization.

“There is no question that the Tokyo Olympics stripped the lacquer off the wider Olympic project for everyday people to see,” said Jules Boykoff, a former Olympic soccer player and an expert in sports politics at Pacific University. “I’ve heard some people talk about how the Olympics are this huge political-economic force with sports attached to the side of it.”

Indeed, athletes’ advocates have accused the IOC of shortchanging the talent that make the Games possible, given that such a small sliver of the organization’s revenues are allocated directly to the competitors. Most of the funds are funneled through national Olympic committees and sporting federations, according to an analysis of IOC funding by Global Athlete, an athletes’ group, and the Ted Rogers School of Management at Ryerson University in Toronto.

The IOC “is supporting an industry and administrators,” said Rob Koehler, the director-general of Global Athlete. “But are they supporting athletes? The proof is in the pudding: no.”

At the Tokyo Games, critics questioned the IOC’s commitment to enforcing disciplinary actions. Athletes from Russia, a country officially banned from the Olympics, competed under the banner of ROC, the acronym for the Russian Olympic Committee. But it was difficult for a casual observer to see how Russia was bearing any real consequences of an enormous state-orchestrated doping campaign as its leaders gloated over its athletes’ many medals.

On Sunday, even as Tokyo organizers officially passed the Olympic flag to Paris for the next Summer Games, the real specter lurking behind the feel-good moments was the Winter Olympics in Beijing, which are scheduled to open in February.

With the postponement of the Tokyo Games by a year, organizers will have just six months to prepare for the next Olympics.

Here again, the actions — or inaction — of the IOC came under sharp examination. Officials, including Bach, avoided answering questions about how the committee planned to address the fact that the Games are to be held in a country that has been condemned for committing genocide and crimes against humanity for its repression of Uyghurs and other predominantly Muslim ethnic minorities.

Large countries — most prominently the United States — will have to decide in the coming months how they might respond to the Games in Beijing.

At the same time, the pandemic is still likely to be a factor. Just as Japan is dealing with a new wave of infections, China, too, is battling new outbreaks of the delta variant in several provinces and has already imposed de facto lockdowns.

The country’s use of sports to promote nationalism was on display at the Tokyo Games, where critics pounced on Japanese athletes in particular if they prevailed over Chinese competitors.

But the Olympics pose risks to the ruling Communist Party and its leader, Xi Jinping.

“The Olympics is either an opportunity to look great, or it could introduce a whole lot of instability,” said Stephen R. Nagy, a professor in politics and international relations at International Christian University in Tokyo. He cited the re-emergence of the coronavirus and possible protests by athletes in Beijing.

But as the cauldron was extinguished and the athletes filed out of the stadium, perhaps the biggest legacy of the Tokyo Games was how it underscored the costs of hosting an Olympics.

For future hosts, said Shihoko Goto, a senior associate for northeast Asia at the Wilson Center, a research institute in Washington, the question is “whether the people of those governments are behind the government effort and the sacrifices that have to be made to put on these big events.”

-New York Times