China protests break out as COVID cases surge and lockdowns persist

By Vivek Shankar

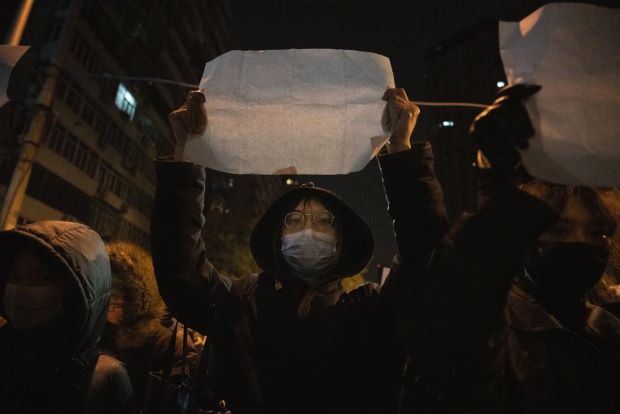

BEIJING – “Lift the lockdown,” the protesters screamed in a city in China’s far west. On the other side of the country, in Shanghai, demonstrators held up sheets of blank white paper, turning them into an implicit but powerful sign of defiance. One protester, who was later detained by the police, was carrying only flowers.

Over the weekend, protests against China’s strict COVID restrictions ricocheted across the country in a rare case of nationwide civil unrest.

On Monday (28), one group supporting the protesters issued online calls for limited numbers of demonstrators to gather at the People’s Square in Shanghai and near a subway stop in northwest Beijing in the evening. But video shared from the two sites, identifiable from the buildings and signs in the background, showed a heavy security presence, with police buses and cars lining the streets.

In the eastern city of Hangzhou, a crowd of people gathered at a shopping mall but were closely watched by an even larger group of uniformed police officers. A woman was screaming as several of the officers took her away, according to videos circulating online. Onlookers shouted at the police.

Some demonstrators over the weekend had gone so far as to call for the Communist Party and its leader, Xi Jinping, to step down. Many were fed up with Xi, who in October secured a precedent-defying third term as the party’s general secretary, and his ‘zero-COVID’ policy, which continues to disrupt everyday life, hurt livelihoods and isolate the country.

The Chinese government on Monday blamed “forces with ulterior motives” for linking a deadly fire in the western Xinjiang region to strict COVID measures, a key driver as the protests spread across the country.

The 1.4 billion-plus residents of China remain at the mercy of the stringent policy. It is designed to stamp out infections by relying on snap lockdowns of apartment buildings and sometimes whole cities or regions, as well as forcing lengthy quarantines and a litany of tests on residents.

Outside China, the rest of the world has adapted to the virus and is near normalcy. Take soccer’s premier event, the World Cup. Thousands of people from across the globe have assembled in Qatar and are cheering on their teams, shoulder-to-shoulder, without masks, in packed stadiums.

China’s approach won praise during the beginning of the pandemic, and there is no doubt it has saved lives. But now that approach looks increasingly outdated. Almost three years after the coronavirus emerged, the contrast between China and the rest of the world couldn’t be starker.

Here’s what you need to know about the situation in China.

A deadly fire in China’s far west has infuriated protesters

The news spread fast on the Chinese internet. Ten people died on Thursday (24) after a fire in an apartment building in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang, a region of 25 million people that had been under lockdown for more than three months. (The region has previously been in the spotlight over China’s mass internment of its Muslim population.)

Many Chinese suspected that COVID restrictions — which can include makeshift barricades and blockaded emergency exits to keep people indoors — had hampered the rescue or prevented residents from seeking shelter from the fire. Many Urumqi residents took to the streets, chanting “end lockdowns.”

Soon, protests erupted across the country.

In Shanghai, China’s largest city, residents gathered at an intersection of Urumqi Road, named after the city in Xinjiang, to mourn the dead. “We want freedom,” they chanted, and some went on to call for Xi’s resignation.

“Those victims, how they died, we are all clear about that. Isn’t that right?” said the protester with the flowers, according to a video posted on social media, an apparent reference to the tragedy in Urumqi. Soon after, the man, nicknamed “Shanghai Flower Boy” on social media, was taken away by police, the video showed. The Times verified the location of the video as Urumqi Road in Shanghai.

Among those who were taken away was a BBC reporter, who was later released.

Demonstrators also gathered in the country’s capital, with many students assembling at Tsinghua University in northwest Beijing to denounce restrictions on their ability to get around. Hundreds of protesters also marched in Wuhan, the central Chinese city where the pandemic originated in late 2019. Crowds have also congregated in Chengdu, a city in the southwest of the country.

On Monday, a government official addressed the claim that there was a link between the Urumqi fire and virus restrictions. “On social media there are forces with ulterior motives that relate this fire with the local response to COVID-19,” Zhao Lijian, a Foreign Ministry spokesman, said in response to a question at a regular press briefing.

China’s economy has been hurt by the restrictions

The disruptions to daily life have hammered businesses both large and small, from the company that makes iPhones to neighborhood shops and restaurants.

A lockdown at a Foxconn facility in Zhengzhou in central China showed how the policy can have global ramifications. After workers were pulled out of their jobs to limit a COVID outbreak, production dropped. That, in turn, forced Apple to warn that its sales would fall short of expectations.

To avoid similar problems, other multinational companies have been looking to expand production outside China.

On the main streets of towns and cities in China, lockdowns have reduced foot traffic, hurting businesses that are vital to urban employment.

According to the latest data, the Chinese economy grew 3.9% in the three months that ended in September. But that was much slower than the government’s target of 5.5% for 2022, and some economists are forecasting that it will fall even more in the year’s final months.

For investors worried about China’s economy, it has been a guessing game as to when, if ever, the restrictions will be rolled back. Many had expected an announcement at October’s Communist Party congress. But instead, Xi doubled down. The immediate market reaction on Monday was muted, with stocks in Asia falling about 1%.

Officials have tried to fine tune the ‘zero-COVID’ policy.

Earlier in November, the government said it would ease some of the rules, even as it remained committed to the policy. The shift was modest, but it was a sign that the authorities were cognizant of the toll the constant disruptions were having on the economy.

Quarantine restrictions were loosened for overseas travellers, as was a penalty system for airlines bringing in travellers with COVID. Within the country, authorities cut back, albeit slightly, contact tracing and eliminated some other measures.

Financial markets initially took it as a positive sign that heralded the eventual withdrawal of the policy. But it was not to be.

With the looser restrictions came more COVID cases that escalated into outbreaks. The daily number of reported cases is at its highest point of the pandemic. Most Chinese have never been exposed to the virus, and a vaccination drive has largely stalled. Officials quickly backpedalled. By mid-November, a third of China’s population and areas that generate two-fifths of its economic output were back under partial or complete lockdowns, according to an estimate from the Japanese brokerage Nomura.

-New York Times

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.