By Syed Mohammad Ali

The populous and tension-ridden South Asia region has seen a recent reduction of internal conflicts but increased intra-state friction and authoritarianism are on the rise.

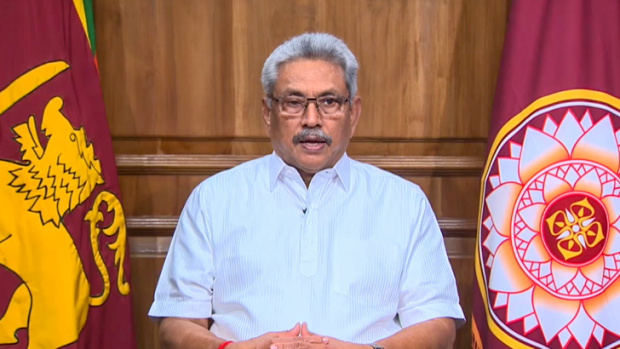

Besides the protracted rivalry between India and Pakistan, Bangladesh has experienced a deterioration of relations with India under the intolerant leadership of Sheikh Hasina. Nepal’s constitution is in danger as Oli moves closer to authoritarianism and Sri Lanka has also seen re-emergence of the strongman Rajapaksa regime. Both Nepal and Sri Lanka have experienced growing tensions with India, as their governments try to come closer to China.

At a quick glance, coercive capabilities of South Asian states have significantly improved, enabling respective governments of the region to bring political violence under control.

Yet, how the security situation has improved across the region, and at what cost, merits further consideration. A closer examination of these issues is important as it offers valuable insight concerning future trajectories and common dilemmas facing the broader region.

It is instructive to look at the work of Paul Staniland, an academic who recently deliberated on such issues for the Carnegie Endowment for Peace, and pointed out how the seeming triumph of South Asian states’ coercive capabilities is accompanied by some worrying trends.

During the first decade of the 21st century, anti-state rebellions were an endemic feature of South Asia’s political landscape. Both separatist and revolutionary insurgencies presented serious challenges. Religious extremism was a major threat in Pakistan. A Maoist insurgency was plaguing Nepal. The contestations between Sheikh Hasina and Khalida Zia led to a spike in political violence in Bangladesh. India was facing multiple insurgent threats, and Sri Lanka was being torn apart by a protracted civil war between the Sinhalese government and Tamil insurgents.

Yet, these threats have been significantly contained over the past few years. India has managed to defuse the threat by separatists including Naxalites and varied insurgent groups in the northeast. Pakistan has brought the threat posed by TTP and other militant groups under control. The Tamil Tigers have been brutally crushed. Nepal’s Maoists have been incorporated into a new political system. Sheikh Hasina’s consolidation over power has led to a significant reduction in political violence.

Major anti-state revolts across South Asia have either been crushed, significantly demobilized, or contained through different forms of accommodation. Underneath the surface, however, there lurk significant chances of resurgent violence.

Using coercive power to suppress violence is not the same as resolving conflict. Yet, no South Asian government seems to have realized this important lesson despite the rhetoric employed by them of ushering in peace and reconciliation. Political exclusion and disenfranchisement continue to brew across former restive regions. The demands of the Tamils, Baloch, Bodo, Naga and people of Assam, have not been paid significant heed. Not only do most of the inequalities and structural disparities which have bred resistance in the past continue to persist, top-down models of economic growth continue exacerbating inequalities which can again be mobilized to fuel further unrest.

Lingering discontent of marginalized groups across South Asia is made more dangerous due to interstate political relations being in a flux, due to risks of cross-border conflicts spiraling out of control, proxy warfare and state sponsorship of militant groups. Indian support to TTP or BLA to push back against Pakistani disgruntlement about the situation in Kashmir, for example, remains a major threat, which will probably worsen with US military’s withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Instead of trying to enhance their coercive power, South Asian states would be better advised to consolidate their gains by negotiating meaningful conflict resolution with disgruntled and marginalized groups before they are compelled to up the ante by resorting again to violence.

-Syed Mohammad Ali holds a PhD from the University of Melbourne and is the author of Development, Poverty and Power in Pakistan, available from Routledge. This article was originally featured by The Express Tribune