Sri Lanka says IMF aid in reach after year of anger, hunger and fear

President hints new China letter will seal deal; fate of local elections in focus

By Munza Mushtaq

COLOMBO – Braving the scorching afternoon sun, 64-year-old K. Piyasena walks along the sidewalk adjoining the sprawling ocean park in Colombo known as Galle Face Green, not far from Sri Lanka’s Presidential Secretariat. “Annasi!” he shouts as he desperately tries to sell freshly cut pineapple halves doused in salt and chili.

“Since morning I have only sold around seven pieces. About a year ago, I would finish selling the entire lot by 2:00 p.m. and go home. But now most people choose not to waste money on these snacks even if they are hungry, because of the cost of living,” he said.

Nearly one year ago, Galle Face Green became the epicentre of a series of peaceful protests that ultimately brought down President Gotabaya Rajapaksa. Now, Sri Lanka may be approaching another milestone, as the government says it is on the cusp of unlocking a provisionally agreed-upon $2.9 billion bailout from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

President Ranil Wickremesinghe on Tuesday (7) signalled that key creditor China had offered new assurances on Sri Lanka’s debt – seen as a key stumbling block toward winning the IMF assistance. “Last night we received a new letter from the China Exim Bank,” Wickremesinghe said. Although it was not immediately clear what China had offered beyond a two-year moratorium seen as insufficient, the president said he expects an IMF green light “either in the third or fourth week of March.”

The government’s hopes have been dashed before. But if the bailout comes through, it would be an anniversary gift of sorts for a nation that began to hit the streets in force in March 2022 to protest Rajapaksa’s economic management. His policies were widely blamed for draining the country’s foreign reserves and triggering the worst crisis since independence from Britain in 1948.

Brutal inflation, daily blackouts and dire shortages of food, fuel and essential medicines drove the #OccupyGalleFace or ‘Gota go home!’ movement, ultimately forcing a parade of resignations. The list included the president’s brother, Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa, and Gotabaya himself, who has kept a low profile since returning from brief self-exile in the Maldives and Singapore.

To this day, the Rajapaksas say they were scapegoated. “As a family, we have done a lot for Sri Lanka and blaming our family is not fair. If [critics] have proof that we are the cause [of the crisis], they must show it,” said Namal Rajapaksa, Mahinda’s eldest son and a Member of Parliament.

Either way, even IMF support would not mean immediate relief for average Sri Lankans hit by a 66% electricity tariff hike in February, on top of last year’s 75%, and new income taxes as high as 36%. Last week, the central bank raised its key interest rates again to try to curb inflation hovering around 50%, while public-sector workers stormed out of hospitals, banks and ports to protest the cost of living.

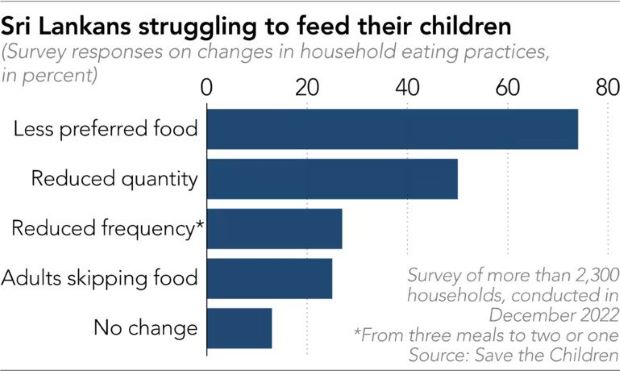

A just-released survey by Save the Children indicated that half of Sri Lankan families have been forced to reduce the amount they feed their kids.

At the same time, the IMF bailout would not ease simmering anxiety over the future of democracy in the nation of 22 million.

President Wickremesinghe replaced Gotabaya last July with the support of the Rajapaksa family and their Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) party, which still enjoys a legislative majority. Wickremesinghe was not exactly popular – he lost in the 2020 parliamentary election and only kept a seat thanks to a bonus system — and he has alienated many citizens by repeatedly deploying security forces to keep a lid on protests, earning the nickname ‘Ranil Rajapaksa’.

Raising further suspicions of anti-democratic intentions was an attempt to indefinitely postpone local elections that had been expected this Thursday (9).

Wickremesinghe reasoned that the country cannot afford the estimated 10 billion rupees ($27 million) it will take to hold them. “We are facing an economic crisis, and we need to plan our spending carefully,” the president tweeted late last month. “We have to keep a reserve in case the IMF funds for which we are negotiating aren’t received in March as expected.”

The president stressed that “we will not have a country if the economy does not develop” and that “only if the country is protected can the constitution be protected.”

Critics found such arguments unconvincing. After all, the government spent an admittedly smaller sum of 200 million rupees in February on a lavish celebration of the country’s 75th Independence Day.

“The government line — that there are insufficient funds to hold an election — is implausible,” said policy analyst Amita Arudpragasam, who predicted the ruling party would “certainly” fare poorly at the ballot box. “Attempts to subvert the Election Commission and delay elections are an attack on what little remains of Sri Lanka’s formal democracy.”

On Friday (3), the Supreme Court ordered the polls to go ahead. A new date was expected to be set on Tuesday.

Many believe the president is wary of voting that would be an indirect referendum on his austerity policies.

“Ranil Wickremesinghe has failed to take into consideration the rights of the people and their suffering,” said Vraie Balthazaar, a Colombo leader in the National People’s Power (NPP) opposition coalition. “For him this is an ego trip, and not about the welfare of the people.”

A 61-year-old NPP candidate, Nimal Amarasiri, died in late February after sustaining injuries at a protest against the election postponement. Authorities used tear gas and water cannons on the demonstrators; a police spokesman told media that the cause of Amarasiri’s death could not be immediately determined.

Although the upcoming elections are only for local councillors, Balthazaar said they would “test the waters” and show that the 6.9 million votes Gotabaya Rajapaksa received in the 2019 presidential election are now “invalid,” and that the 134 parliamentary votes that elected Wickremesinghe are “also void.”

Government insiders reject the notion that the administration is trying to undermine democracy.

“There are no such attempts, but the issue is purely due to financial difficulties,” said Ramesh Pathirana, a member of Wickremesinghe’s cabinet. The minister for plantations and industries said the main priority now is to pay salaries, as well as pensions and support for low-income earners. “The treasury will release funds for the election as and when they get it,” he said.

Few would deny that Wickremesinghe inherited a tough job. He was tasked with righting a badly listing economic ship while meeting IMF expectations on debt and fiscal sustainability. “People have a right to be concerned about the economy, which affects their lives,” Wickremesinghe acknowledged in an interview about a month after he took office. “There has been a drop in living standards … a drop in their purchasing power.”

But he has argued that political stability and sacrifices are essential for rebuilding. In February, he told Parliament, “If we endure this hardship for another five to six months, we can reach a solution.”

The IMF, which also acknowledges the heavy strain on the public, has insisted that tough changes are necessary.

In a statement to media regarding the unpopular tax hikes, Senior Mission Chief for Sri Lanka Peter Breuer and Mission Chief Masahiro Nozaki noted that Sri Lanka’s ratio of tax revenues to gross domestic product was only 7.3% in 2021, among the lowest in the world. They said that “tax reforms are needed to correct this imbalance” as well as to regain creditor confidence. “The tax package the authorities have introduced, including the new tax rate schedule for the personal income tax, helps to meet these objectives.”

At least one positive glimmer is the tourism industry, which is starting to rise from the depths of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The country known for some idyllic beaches recorded 228,434 arrivals in January 2020, before the virus swept the world, but then the figure dropped to zero from that April to November. This is considered a key reason for the depletion of foreign reserves, alongside others, including the Rajapaksa government’s much-criticized insistence on making debt repayments that the country could not afford.

But with global travel now picking up again, Sri Lanka welcomed 102,545 visitors this January.

Nevertheless, about one year after the masses converged on Galle Face Green, the road ahead still looks rough. Some lament that despite their success in ousting the Rajapaksa clan, the protesters did not — or could not — force more fundamental changes to a system that enabled what many believe is rampant corruption.

Sri Lanka ranked 101st out of 180 countries on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index for 2022.

Prasad Welikumbura, an activist in Colombo who took part in the protests from the very beginning, said the movement lost steam for multiple reasons. He believes one factor was fear of the government using force to curb demonstrations. A violent crackdown on the Colombo protest camp set the tone in the early days of Wickremesinghe’s presidency.

Welikumbura also said the severity of the economic crisis has compelled many Sri Lankans to do extra overtime, take second jobs or find side projects to put food on the table, leaving little time to demonstrate.

“Due to this, we can no longer see a unified mass action against government suppression and its austerity policies. Only trade unions and the opposition student movement at the university level are trying to unify the people outside of party politics,” he said.

Bhavani Fonseka, a constitutional lawyer and senior researcher at the Centre for Policy Alternatives think tank, noted that last year’s protests resulted in regime change but did not “follow through” on demands for reform of the entire system.

A year later, according to Fonseka, nothing has come of calls to abolish the executive presidency along with demands for greater transparency and accountability. “Sri Lanka’s democracy is very fragile, and if the citizens don’t take charge and robustly defend [it] then we will see darker times,” she warned.

At least in public, the Rajapaksas still appear confident that they can win over the electorate again.

Namal Rajapaksa said that despite the Gotabaya’s presidency being overshadowed by the pandemic, “we did a lot of development including restarting industries. So we believe at the next election we have a good opportunity to strongly come back, because we have faith in our party base and supporters.”

He also denied corruption allegations against the family, saying that they had been investigated but nothing was ever proven.

The only way to test predictions of electoral doom or vindication is to hold the balloting. Jayadeva Uyangoda, a professor of political science at the University of Colombo, agreed that the ruling party is “very scared” of a disastrous outcome and thinks this could mark the beginning of a very serious crisis for it.

“It will also set the trend for the outcomes of the next provincial, parliamentary and presidential elections,” he said.

Uyangoda argued that the present political class — beneficiaries of what he sees as a corrupt and ineffective system of governance — needs to be substantially reformed or replaced.

Arudpragasam, the policy analyst, agreed that a true transformation is not possible with the current set of lawmakers in Parliament. She said this is why it is critical to defend the electoral process.

“Long-term transformation,” she said, “requires institution-building, education and a dismantling of the big-money politics that created this economic and political crisis.”

-This article was originally featured on asia.nikkei.com

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.