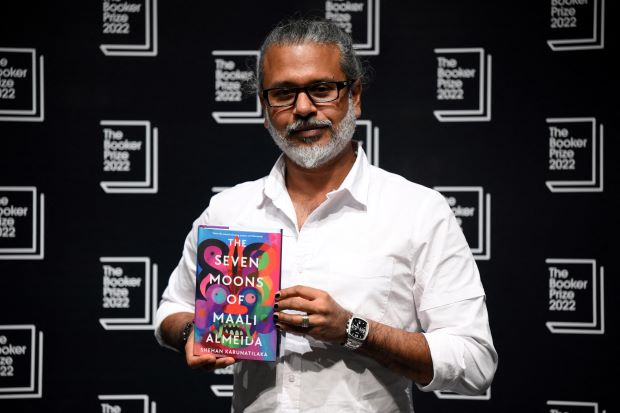

Booker Prize winner lets ghosts of Sri Lanka’s past speak

By Jill Lawless

LONDON — Shehan Karunatilaka wrote his Booker Prize-winning novel ‘The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida’ to give voice to Sri Lanka’s dead. He hoped the ghosts of the country’s bloody past could speak to its troubled present.

When the book became a finalist for the 50,000-pound ($58,000) fiction award this summer, protests over a deepening economic crisis gripped Sri Lanka. An uneasy calm had returned by Oct. 17, when Karunatilaka’s novel won the prestigious prize, catapulting its author to literary stardom.

“Surreal” was the word Karunatilaka used to describe edging out finalists who included Americans Percival Everett and Elizabeth Strout with his novel about a war photographer who wakes up dead. Stranded in a bureaucratic limbo of an afterlife, Maali Almeida has a week – seven moons – to discover who killed him and retrieve a trove of photos to secure his legacy.

The book is set in 1989, during Sri Lanka’s brutal civil war – a time, the author says, when “we had an abundance of corpses, an abundance of unsolved killings.”

The book looks unflinchingly at the violence of war, shot through with what Karunatilaka calls Sri Lanka’s characteristic “gallows humour.” Neil MacGregor, who led the Booker judging panel, said it found “joy, tenderness, love and loyalty” in “the dark heart of the world.”

Karunatilaka, 47, started writing it a decade ago, soon after the country’s long civil war ended.

“There was a lot of debate over how many civilians had been killed and whose fault it was — and the debate got us nowhere,” Karunatilaka told The Associated Press. “I didn’t feel there was enough truth or reconciliation. It was just one side blaming the other side and trying to just apportion whose fault it was rather than addressing the causes.

“And so I (thought), what if we could allow these silenced voices to speak? What if we could have a ghost story where the dead were allowed to speak?”

Writing novels can be a dangerous business – a risk driven horrifyingly home when Salman Rushdie was stabbed and seriously injured during an August literary event in New York state.

Karunatilaka says the fear of violence is “something that hangs over all of us.”

“I don’t see myself as a political writer or someone who courts controversy,” said the author, a polymath who has written journalism, children’s books and screenplays, once belonged to a grunge band and has a day job as an advertising copywriter.

But, even so, writing about the post-civil war period felt “too close. And also, it might have been unsafe, it might have ruffled the wrong feathers.”

Setting his novel more than 30 years in the past “allowed me the freedom to write about it.”

Karunatilaka says he is gradually catching up with the present. He is setting his next book in the early 2000s, and he says he’s “taking notes” about this year’s dramatic events in Sri Lanka.

Sri Lankans protested for months over an unprecedented economic crisis that has led to severe shortages of essential imports such as medicines, fuel and cooking gas. Thousands stormed the president’s residence in July, forcing then-President Gotabaya Rajapaksa to flee and later resign. Footage of protesters swimming in the president’s pool and sleeping in his bed were beamed around the world.

Karunatilaka says humour, a major ingredient in his fiction, is also key to resistance and change.

“When you laugh at something, it has less power,” he said. “And I think we were unable to laugh at the government maybe a decade ago, but something changed. Maybe it was the pandemic, maybe it was the fact that the interim government restored the freedom of the press. But people seemed quite bold enough to make jokes about those in power and ultimately were emboldened enough to take to the streets and get rid of them.”

The country’s new president, Ranil Wickremesinghe, has cracked down on opposition. But Karunatilaka hopes the protests were a turning point.

“It was something spectacular because it wasn’t just the radical fringe or the young who were out there. It was everyone. It was the working class who had travelled many, many miles to get there without petrol. There were grandmas, there were kids.

“And it was like the ordinary citizenry had put aside all these things that divided us … and they were united across generations and races and religions with this common goal of getting rid of the people who had got us into the situation.

“So I really hope we don’t go down the route again of silencing dissent, which didn’t work for us in 1989 or in any of the decades since,” he said.

-Associated Press

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.