Oddamavadi: No rest for the dead

Two years ago, the government passed a compulsory cremation policy for those who died of COVID-19, with no clear reason for it other than hyper nationalism and xenophobia. After months of campaigning and pressure both locally and internationally, the gazette on the subject was revoked. Instead, families had to bury their dead in a far-flung village in the East, and supply funds and labour - despite the government sitting on billions raised by the Itukama fund

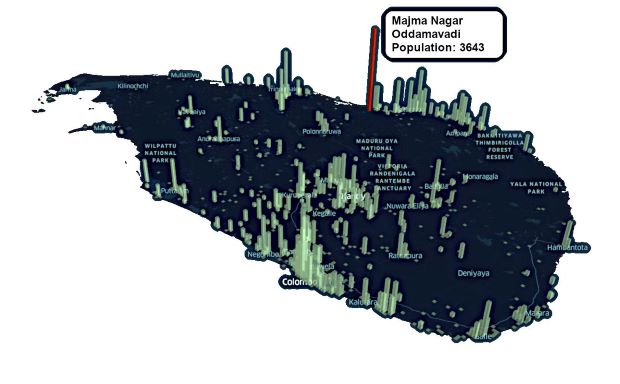

- Between March 2021 and March 2022, over 3600 people (predominantly Muslim) were buried in a lot in Oddamavadi after a period of forced cremations

- Local villagers lost their land to create space for the burial ground; of 21.5 acres allocated for the site, only 10 acres are used — the remainder serves as a ‘buffer zone

- ’Locals claim the national government did nothing to compensate or contribute towards costs, despite promising to do so, and despite the COVID-19 relief fund

The cruel fire

A dusty white truck slowly trundles away after unloading the bodies of people who died of COVID-19. In the quiet vastness of Majma Nagar, Oddamavadi, the only sounds are that of the backhoe slowly filling fresh graves up with sand.

To understand why we’re here, it’s important to first understand the cruelty of forced cremations in Sri Lanka.

In April 2020, the Government of Sri Lanka passed a gazette notification which enforced mandatory cremations for people who died of COVID-19.

The government’s decisions were made to a backdrop of general misinformation that Muslim communities spread COVID-19. After all, just prior to the policy going into play, the Government Medical Officer’s Association (GMOA) and the Information and Communication Technology Agency Sri Lanka (ICTA) presented a COVID-19 strategy proposal to President Gotabaya Rajapaksa. In it, they assigned the Muslim population the highest weightage of risk when determining the risk of the spread of the virus in each district.

While the report was later retracted, Sri Lanka’s health authorities claimed that the virus spread through groundwater and decided to cremate those who died of COVID-19 — a decision that would largely affect Muslims in Sri Lanka, as religious duty calls for burial of bodies and the delivery of last rites.

Eminent researchers, including epidemiologist Dr Malik Peiris, pointed out that COVID-19 does not spread through dead bodies; interim guidance by the World Health Organization (WHO) pointed out that COVID-19 victims can be either cremated or buried — with no mention of groundwater contamination — and that ‘families and traditional burial attendants’ can be part of the burial process.

However, the government’s decision, seen to be yet another Islamophobic missive, was defended by Dr Channa Perera, a Consultant Judicial Medical Officer and a specialist in Forensic Medicine who was also the director of the COVID-19 Deaths Management Committee. According to Perera, authorities ‘had to take certain measures to safeguard the community’ because of ‘not having a clear idea of how the virus works.’ These fears were further propagated by the government’s Chief Epidemiologist Dr Sugath Samaraweera; who informed the BBC that the government was ‘following expert medical advice’ as ‘burials could contaminate ground drinking water’.

The cremations were forced; with bodies of everyone from babies to the elderly subjected to the same process. Some families were not even allowed to see their dead; it appears that families were informed, seemingly ad-hoc, after the fact. A combination of indifferent hospital staff, police ‘just following orders’, and a complete lack of communications left families traumatized and outraged.

After nearly a year of canvassing and appeals from the international community, the government finally issued a gazette permitting burials; on the condition that it would be ‘in accordance with the directions issued by the Director General of Health Services at a cemetery or place approved by the proper authority under the supervision of such authority’.

According to Dr. Anver Hamdani, Coordinator in charge of COVID-19 at the Ministry of Health, the decision came after months of long discussions by the Technical Committee of the Ministry of Health.

“Many people requested the ministry to grant permission to bury those who died of the virus in cemeteries closer to them, across the island. This matter was under review by the Technical Committee since December 2021, and the decision to approve burials was finally granted on March 5, 2022,” he said.

The technical review may not have been the only reason for revocation. Rauff Hakeem, Member of Parliament and leader of the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress (SLMC) claimed that it was pressure applied by the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) that led to abandoning forced cremations.

Sometime later, the military and officials from the health ministry eventually settled on a site at Majma Nagar, Oddamavadi, in the Batticaloa district; a lot across the street from a garbage dump. This is around 290kms away from Colombo.

Nowhere else could the dead be buried: and so began the stream of bodies, piled in a solitary field in the shadow of waste. From March 2021 until March 2022, a total of 3634 people have been buried here.

Over the last year, families travelled literally hundreds of kilometres, accompanying the bodies of their loved ones. A vehicle with the whole family might make the journey, but only two persons were allowed beyond the turn-off at the main Colombo-Batticaloa road to the borders of the site. Others had to disembark at what is marked on Google Maps as the ‘Oddamavadi Janaza Point’, do their necessary prayers in a small tin hut, and wait for the people accompanying the body to return.

Once vehicles drive along the sand and potholed road to the gravesite, there is a checkpoint at the final turnoff, and another at the resting place. Between these two, vehicles must pass by what was once a garbage dump – now cleared out completely, down to an expanse of flat, churned land.

A police officer and an army officer wait at the small ‘takaram’ hut, on which the beating rain hammers loud. All of these are marked ‘Al Noor Charity Foundation’.

To look upon Oddamavadi is to look upon what is essentially a mass grave. The markers bear no names, only numbers.

The village of the dead

From the beginning, Oddamavadi had issues

-The first was around land

Of the 21.5 acres of land allocated for burials, only 10 acres are used — the remainder serves as a ‘buffer zone’ which surrounds the burial sites.

According to S. Shihabdeen, Secretary to the Oddamavadi Pradeshiya Sabha, the District Secretary and military asked them to identify a suitable plot of land for the burials. The one recommended by the Sabha, though, was rejected by the Ministry of Health and the military’s technical committee, stating that the land was too low-lying for the purpose. A different plot of land was identified – one which was used for agricultural purposes. As the bodies piled up, land acquisition grew, and the residents of Oddamavadi began to worry.

A.L Sameem, President of the Rural Development Society at Majma Nagar, said people lost their agricultural and residential lands to the ‘buffer zone’, pointing out that approximately 320 families who were displaced during the war were resettled at Oddamavadi — and that their entire livelihood revolved around agriculture.

“The villagers face a lot of difficulties in their day to day lives, from accessibility to fresh drinking water, lack of toilet facilities, and road infrastructure. Amidst these, 14 villagers lost their land to the COVID-19 burial site, and didn’t receive any compensation for their losses.”

The first person to donate three acres of his land was a person called Jawfer, who claimed he donated his land without any expectations. “It’s not just Muslims who are buried here, even people from other religions wanted to save the bodies of their loved ones from fire. My land is nothing in the face of that need. I spoke to my wife, got her consent, and handed the land over immediately.”

Jawfer said he was contacted by numerous wealthy Muslims who wanted to contribute cash to him for his service, which he declined. However, if the government was to provide an alternative plot of land, that’s something he would accept to continue his cultivations, he said.

This isn’t the case for many others. Adjacent lands belonging to 13 others were taken without consent. One was M.A. Muhideen (49), also of an agricultural background. “The Divisional Secretary summoned us and told us that alternate lands will be provided within 10 days of ours being taken. It’s been over a year now, and we’ve not gotten anything at all,” he said sadly.

The Pradeshiya Sabha wrote to the Ministry of Health about this several times, and also met the Army Commander for the Eastern Province. Nothing came of it until February 2022, when the government finally allowed for burials in local cemeteries.

– The second problem was the lack of government support

The burials were under the mandate of the National Operation Centre for Prevention of COVID-19 Outbreak; yet at the end of the day, it was left to Oddamavadi Pradeshiya Sabha and the community to bury bodies and maintain the site.

According to A.M. Naufer, Chairperson of the Oddamavadi Pradeshiya Sabha, the government did not extend financial support of any sort for the thousands of burials that took place within the course of the year. The Pradeshiya Sabha allocated a JCB excavator for the site – and also had to cover its fuel and repair costs.

“We’ve been under lockdown thrice during the pandemic… It’s pathetic that the government failed to allocate a single rupee for this cause, especially at such a time,” Naufer said. Corroborating this was the S. Shihabdeen, Secretary to the Pradeshiya Sabha, who noted that it was the community’s generous donors that helped cover most expenses.

“We had 11 people helping out with burials, and gave them a small allowance. Even this was possible only because of some Muslim welfare organizations in Colombo, who contributed to this. Even the signposts that are in place as headstones were donated by wealthy Muslims,” he added.

The families of the dead were not charged for any of these services, he added. “We did this as a public service that was entirely free.”

“No one was ready to do the burials — we had no one,” said Jeffry and Rafeek, two volunteers. “The army told us (the Pradeshiya Sabha) that they would only transport the bodies here, and we had to take care of the rest. There were a lot of deaths in the community; and, because people were afraid of infections, no one in the village would get too close to us either, as they were afraid we would infect them after being involved in the burials…”

According to Bimal Ratnayaka, former MP, the economic burden of transporting the bodies to the burial grounds falls to the families of the deceased — with costs from Jaffna to Oddamavadi for instance, coming to Rs 85,000. Contrary to this, Dr. Anver Hamdani told Watchdog that the Sri Lanka Army bore the transport costs from the hospital to the burial ground.

“If relatives want to visit Majma Nagar to be part of the final rituals of their loved ones, they can do so, but will have to cover their own costs. However, the army took care of transporting the bodies – and the costs associated to it were paid by the army,” he reiterated.

We knew that the Mosques Federations of the Colombo and Kandy districts were also coordinating the transportation of bodies, in collaboration with the Ministry of Health and the army. With this in mind, we reached out to Aslam Othman, Secretary of the Mosques Federation in Colombo, to learn more.

According to Othman, bodies from the Eastern Province were transported directly to Majma Nagar, while those who died in other parts of the island were first taken to either Colombo, Kurunagala, or Anuradhapura before being ferried to Oddamavadi in an army convoy. Othman also commended the services rendered by the army with regards to this.

“The government didn’t provide a lot of economic assistance. The army bore the responsibility of transporting dead bodies completely and provided necessary transport and manpower. However, wealthy people in the Muslim community provided all the coffins needed. Each coffin at the time cost around Rs 4,500, and we were able to provide over 1000 so far.”

But what about Itukama, the COVID-19 fund?

Itukama is Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s national fundraiser for ‘healthcare and social security’ and to ‘support the brave heroes on the frontlines of the battle against COVID-19.’

The former president’s widely advertised effort brought in over two billion rupees, Rs 2,024,953,352.70 to be precise (or, two billion twenty four million nine hundred fifty three thousand three hundred and fifty two rupees, and seventy cents).

Watchdog submitted an RTI (Right to Information) request to know what the money was used for, and how much of it was spent. Of over two billion, the total amount dispersed was a mere Rs 197, 476, 824 – aka one hundred ninety seven million four hundred seventy six thousand eight hundred and twenty four rupees.

The funds were issued only to State bodies, and not a single rupee was disbursed towards any of the provincial councils, nor was anything spent on costs at Oddamavadi.

Here’s a breakdown of the expenses and the ministry affiliated with it:

| Activity | Expenditure (LKR) | Implementing agency |

| PCR testing | 42,605,812 | Ministry of Health; University Grants Commission |

| Advocacy Program | 67,543,967 | Ministry of Health |

| Quarantine facilities | 38,031,065 | Ministry of Health; Ministry of Defence |

| National Vaccination Programme | 41,545,980 | Ministry of Health |

| Purchase of ICU beds | 7,750,000 | Ministry of Defence |

Over 67 million was spent on ‘advocacy programs’; none was sent towards the mass grave of over 3000 bodies. As of the time of our investigation, there was approximately Rs 1,827,476,528 in balance unused and unaccounted for.

Counting bodies

In March this year, Watchdog set out to examine Oddamavadi: in addition to site visits and interviews, we also obtained the logs — often maintained by the volunteer burial workers — of those interred there. These are the snippets you’ve seen throughout this story, with the names encrypted and addresses trimmed to protect privacy.

Mapped out, this is what the data shows us.

The scale of the trauma dealt is national, to say the least. From all across Sri Lanka come the dead — that’s them in green. And with them, their loved ones; making a cruel pilgrimage – especially in the middle of an ongoing economic crisis – for closure. Their destination is the red tower highlighted in the map — Oddamavadi. When the pandemic was at its peak in August 2021, an average of 40-60 bodies were buried on a daily basis. Every population centre in the country has a tale of suffering, written into this tragedy by an irrational, racist policy and neglect.

It isn’t just the Muslims who are buried here. A significant number of the buried population are from Buddhist and Hindu faiths. Looking through the data, one is struck by entries like this.

![]()

There are unknown bodies left here, discarded, and interred. There is a seven-day old infant and a 103 year-old woman. There are foreign nationals buried here. There is the sheer thoughtlessness of the cruelty on display, hiding behind bureaucracies and press statements.

Walking through the graveyard

Even though burials at Majma Nagar are now officially over, the site, as of the beginning of August, remained under control of the army. Two military checkpoints were still in operation; no-one was allowed to enter without permission. Two officers at the checkpoint would take down your name, address, ID number, phone number and check the photo on a small token that proves that loved one is indeed buried in this mass grave. It was the size of a business card – white, printed with the words ‘Keep ourself from / අපව වළක්වන්න / எம்மை பாதுகாப்போம் COVID-19’. The card bore the name of the deceased and their ‘grave’ or serial number.

Once this registration is complete, the officers would say that family may now ‘look’ at the site. ‘Look’, from the yellow police tape that marks a fluttering ‘boundary’ along one small section of the graves. People would arrive hoping to pay tribute to their loved one’s final resting place, but instead have to utter their prayers and grief towards the whole graveyard, scattered with short tombstones.

When we began interviewing people for this story, S. Shihabdeen, Secretary of the Oddamavadi Pradeshiya Sabha, had requested the authorities to hand over the authorization of the burial site to the Oddamavadi Pradeshiya Sabha, and to offer rewards or compensation to those who volunteered their time and effort to work on the site.

Indeed, on August 17, the military handed over the site to the Pradeshiya Sabha and left; now family members can visit without prior permission.

Shihabdeen’s future plans involve making the place more accessible as a park that families of the deceased can visit and walk through. Paths for foot traffic, as well as small buildings in which people can stay at for a while after making a long journey.

To do this, he hopes there will be some support from the government, even though there has been none so far.

On March 5, 2021, two months or more after his death, was when Muhammed Siddeek was finally laid to rest. He was 63 years old, and was one among nine others who were waiting for their burials; and who were buried on the first day the site was established. His living relatives were visited by the police several times during this in-limbo period of being dead, but deep-frozen above ground. They attempted to force the family’s consent for cremations. They had to get an enjoining order to keep Siddeek from the pyre.

“Maama (uncle) died when the mandatory cremation policy was in force, and was only buried 70 days after his death,” his son-in-law, Mohamed Amjath tells us. Until then, the family was plagued by the worry of whether or not they would wake up to the news of another forced cremation.

As Muslims generally bury their dead within 24 hours, Amjath recollected how stressful the months leading to Siddeek’s burial was, and how none of them could get a peaceful night’s sleep.

“Those were very harsh and cruel days.”

–Story by Mohamed Fairooz, Aisha Nazim, Amalini De Sayrah; Edits and data analysis by Yudhanjaya Wijeratne and Tineeka De Silva’ Photos by Amalini De Sayrah, Abdul Baazir, Mohamed Faris’ Translated by Nishadi Gunatilake and Kesavan Selvarajah – longform.watchdog.team/observations/oddamavadi-no-rest-for-the-dead

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.