Kerala’s unrecognized historical connection with Sri Lanka

By P. K. Balachandran

COLOMBO – While Sri Lanka’s connection with the Tamil country in South India is repeatedly mentioned in the island nation’s ancient chronicles, the Mahawamsa and the Deepawamsa, its connection with Kerala, which is also in South India, finds no mention in either.

Kerala appears for the first time only in the Chulawamsa, a sequel, in a 10th Century AD context, points out Dr. Amaradasa Liyanagamage, in his work: Society, State and Religion in Pre-modern Sri Lanka (Social Scientists Association Colombo, 2008).

According to the Chulawamsa, an un-named Pandyan king had landed in Sri Lanka as he was being relentlessly pursued by a Chola king, and had sought military help from the Sinhalese ruler Dappula IV (924-935 AD). But since Dappula IV was in no position to help, the Pandyan king had taken refuge in Kerala.

Thereafter, the Keralas (or Malayalis as they are known now) began to figure in Sri Lankan history as mercenaries in the armies of Sinhalese kings along with other South Indians like Tamils and Kannaatas (presumably Kannadigas from present-day Karnataka). According to the Chulawamsa, South Indian mercenaries were in Sinhalese armies from the reign of Ilanaga (34-44AD) and Abayanaga (236-244 AD). These were the earliest Sri Lankan rulers to have captured their thrones with the help of South Indian mercenaries including those from Kerala, Dr. Liyanagamage notes.

South Indian mercenaries, including Keralas, were involved in campaigns to unite Sri Lanka. They were part of the army of Parakramabahu I (1153-1186 AD) during his campaign to unify Sri Lanka. It is stated that an official with the title Malayaraja was put in charge of Damila (Tamil) troops.

“The useful contribution made by these mercenaries must have been the dominant factor in the continued recruitment of mercenaries such as the Keralas over the centuries by Sinhalese kings,” Dr. Liyanagamage observes.

The South Indian mercenaries, not being local rivals, were not seen as threats by the Sinhalese kings. This was a major reason for their recruitment to the local armies. They were also seen as trustworthy guards. Dr. Liyanagamage points out that the Sacred Tooth relic (a symbol of royal legitimacy in Sri Lanka) was guarded by ‘Velakkara’ troops who were South Indian mercenaries. He states that if paid well and on time, these mercenaries were good soldiers. But if not paid on time they rebelled as they did when Mahinda V (982-1029 AD) reneged. The king had to flee leaving his domain to his Kerala troops.

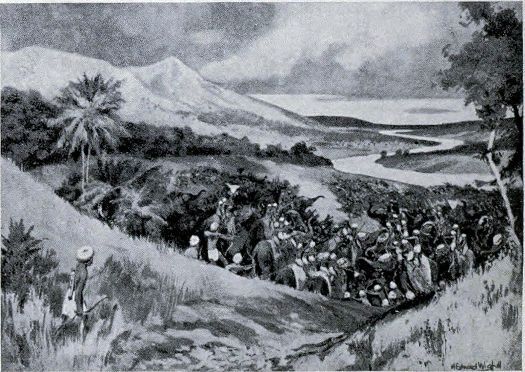

The Kerala mercenaries became a force to be reckoned with in the second decade of the 13th Century. But at this stage, they did not cover themselves with glory. Dr. Liyanagamage quotes the Chulawamsa to highlight that the Keralas were part of a 24,000 strong invading army of a tyrant called Magha from Kalinga (modern-day Odisha) in Eastern India. This army, recruited by Magha from Kerala on his way to Sri Lanka, indulged in unbridled plunder and pillage in Rajarata, destroying even Cetias. When Magha seized Pulattinagara (Polonnaruwa), he handed over Sinhalese Buddhist properties to the Kerala soldiers. Dispossessed, the Sinhalese Buddhists fled to the southern parts of the island. The Chulavamsa describes Magha’s troops as Kerala Rakkhasa or Mara Yodha.

Magha’s 40-year reign (1215 to 1255) saw him consolidating power by building forts in the North-West, Northern and the North-Eastern littoral. It was Parakramabahu II (1236-1270 AD) who ended Magha’s tyrannical rule.

Magha’s reign had spelt the ruin of Rajarata, its civilization, culture and economy, which constituted an organic whole, asserts Dr. Liyanagamage. He also notes: “There is little doubt that among the various factors which led to the decline and collapse of the Rajarata civilization, Magha’s repressive regime backed by the massive Kerala army deserves to be underlined. The irrigation network, which was the basal pivot of the ancient Sinhalese civilization, had suffered immensely, evidently not due to wanton destruction but as a result of neglect and disrepair.

“The military-oriented regime of Magha was ill-suited to generate the atmosphere in which the massive hydraulic systems of Rajarata could function smoothly. With the exodus of Sinhalese nobility, defeated and confiscated of their wealth, Magha was deprived of the backbone of the bureaucracy, which was so vital in the successful operation of the irrigation system.”

In Dr. Liyanagamage’s assessment, Magha dealt the ancient civilization of Rajarata “the final and shattering blow from which it never recovered. And the jungle tide swept over the Northern plain, which had been the cradle of the Sinhalese civilization for over a millennium.”

Be that as it may, with the Rajarata passing into the hands of Magha, Sinhalese kingdoms in South, Centre and West Sri Lanka, came to prominence. Gampola-Senkadagala at the Centre and Jayawardenapura Kotte near Colombo, rose over a period of 300 years.

With the centre of Sinhalese authority moving from the Dry Zone to the Wet Zone, there was a significant change in the pattern of agriculture. Rain-fed agriculture replaced irrigated agriculture. There was also a change in the pattern of political authority. Centralization was possible when the land was flat, as in Rajarata. But the lay of the land in the West and Centre being uneven was not conducive for centralization. This gave rise to the emergence of many centres of power, Dr.Liyanagamage explains. Principalities like Dambadeniya, Yapahuwa, Kurunegala, Kotte, Gampola and Senkadagala emerged. Political unity became difficult to achieve.

By the middle of the 13th Century, South Indian mercenaries had settled down in large numbers in the Northern peninsula, where the Tamil Ariyachakravartis had taken over. Traders from South India had settled down in Mahatittha (Mantai), Sukaratittha (Kayts), and Gokanna (Trincomalee). While the Sinhalese abandoned Rajarata to move South, the Damilas and Keralas moved northwards to Jaffna, Dr.Liyanagamage says.

By the 14th Century the Aryachakravartis had risen to great heights as a power. They began to invade the South. Historian Paranavitana mentions a king called Ariyan in Kotagama in the Kegalle district. Gampola has evidence of an Ariyachakravati invasion at the time of Vikramabahu III (1357-1374). An inscription mentions a grant to Brahmanas by one Savulupati Martandam Perumalun Vahanse. The Alakeswarayuddhaya (16th Century) and the Rajavaliya (18th Century) mention dues collected by Ariyachakravartis from the Udarata (hill country) and the Pahatarata (low country).

Subsequently, two traders (Vanika) families from Kerala, the Alagakonaras and Alakesvaras, began to play a dominant role in defending Sinhalese territories against the Northern Tamil invaders. The Alakesvaras had married into the Gampola Sinhalese royal family of Vikramabahu III (1357-1374). Three brothers of this family, Alagakomara, Arthanayaka, and Devamantrisvara, were ‘joint husbands’ of Princess Jayasiri, the sister of Vikaramabahu III.

By the middle of the 14th Century, the Alakesvaras had reached the zenith of power. They organized military resistance against the Tamil invaders (Ariyachakravartis) from the North when they attacked by land and sea. Fighting had taken place in Colombo, Panadura and Matale.

Besides fighting for the Sinhalese kingdoms, the Alakesvaras and Alagakkonars fostered Buddhism and won the praise of Sinhalese Buddhists. The Alagakkonars laid the foundation for Parakaramabahu VI’s (1415-1467) successful campaign to subjugate the Jaffna kingdom ruled by Kanaasuriya Cinkgaiariyan in 1453-54.

Dr. Liyanagamage regrets that not enough credit is given by modern Sri Lankan historians to the Alakesvaras. But for the contributions of the Alakesvaras, Parakramabahu VI’s task of defending the Sinhalese and subjugating the Northern ruler would have been “more difficult if not impossible.”

Though in the middle of the 13th.Century, the Kerala troops of Magha were extremely destructive, in the middle of the 14th Century the Kerala family of Alakesvaras was helping the Sinhalese subdue the Tamils of the North, though the latter too were of South Indian origin.

-ENCL