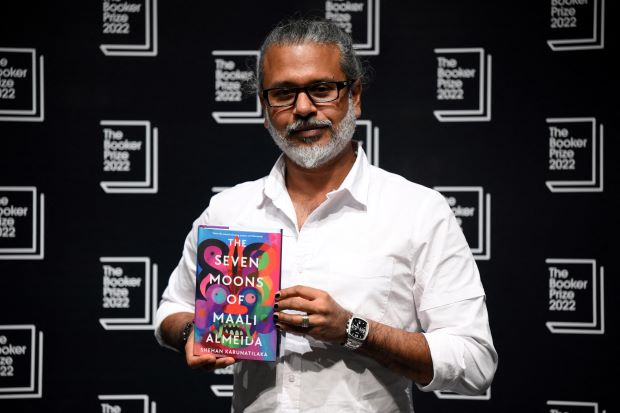

Booker-winner Shehan Karunatilaka: He deserves every accolade, we deserve his lampooning

By Andrew Fidel Fernando

A little over 30 years ago — the period in which the Booker Prize-winning Seven Moons of Maali Almeida is set — four separate militant groups were driving their boots into Sri Lanka’s belly. There was the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), the Tamil separatist force which, according to the book’s protagonist, is “prepared to slaughter Tamil civilians and moderates” to free their people from the state. Also, in the North was the Indian Peace Keeping Force, known colloquially as the Indian People Killing Force, who’d “burn villages to fulfil their mission”. The Marxist Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), who would “murder the working class” to liberate them from capitalism, cut a bloody swathe through the South. And of course, there’s always the Sri Lankan government’s military, whose violence has outcompeted the other three, and now revels in its monopoly.

In descending into one of the darkest phases of Sri Lanka’s modern history, Shehan Karunatilaka creates a roiling world made more tumultuous by the puzzling mechanics of the afterlife. Maali Almeida is dead before the novel begins, and has a week (seven moons) to help his friends find his killer. There are bumbling cops, self-serving NGO types, corrupt politicians, cat-killing thugs, and murdered writers and activists who play roles in the afterlife. The ghosts Karunatilaka’s protagonist meets in the afterlife are themselves haunted by the traumas endured in various phases of Sri Lanka’s history. In the author’s masterful hands, all this is a setting for comedy.

In a year in which Sri Lanka has nosedived again into crisis, the laughs that Seven Moons delivers are especially resonant. Economic distress of this magnitude is a fresh flavour of dysfunction for the island. And yet, in a profound sense, it is a consequence of the horrors of the late 1980s and early 1990s. Many of the political players who rose in that period are now running the state. Sri Lanka’s current president, accused of brutally crushing the Marxists then, is one example. The Rajapaksa family is another.

As police and the Special Task Force fire expensive rounds of tear gas into crowds of protesters who can barely afford to feed themselves, Sri Lankans are once again contending with a state whose default setting towards its subjects is disdain. This time even Sinhalese, often perpetrators, are being roughed up — beaten with truncheons and thrown en masse into jails for merely exercising civic rights.

In the past two weeks, cops used force on parents who had brought small children to a beachside vigil. Faced with an uproar on social media, the country’s president accused these parents of endangering their children, and instructed the police to remove kids from protests in order to protect them from the violence the police themselves instigate.

How else to process such absurdity than through humour? In a nation that lurches from ethnic war, to socialist uprising, to religious terror (of more than one stripe), to mismanaged natural disasters, a crashing rupee, and widespread hunger, all of which are underpinned by industrial-scale corruption and insidious class warfare, what else to do but laugh? If you didn’t, you’d never stop crying. And it is in that mirth that many Sri Lankans find the means to pick themselves up, to move on, to bravely continue the war they must wage against circumstances that are, in part, of their own devising. If the British have a stiff upper lip, hardship tends to draw from Sri Lankans the opposite reaction — a full repertoire, from that much-exoticized smile to the gut-busting guffaw. The worse our politics seems, the better the memes get.

For those who live in Sri Lanka, there is little wonder that the country continues to produce comic geniuses such as Karunatilaka. It is an island on which baila musicians make hilarious jaunts into the realm of satire, whose YouTube stars invent skits that cut to the very heart of Lankan life, whose newspaper cartoonists convey ideas in one frame that policy wonks would take many thousands of words to get across in pompous op-eds. It helps that Sri Lanka’s politics continues to be spectacular fodder. This is, after all, the island that in 2019 voted in a strongman whose family styled him “the terminator”, but who, less than three years later, was chased out of the nation, having terminated only the economy.

What is unmissable about Karunatilaka’s writing is that although he wields his wit as a rapier, you sense the genesis of every joke was the pain that is the right of every domiciled Sri Lankan. The gags are sharp, but they are warm. In the week his book was longlisted for the Booker, he withered for hours in fuel queues, same as everybody else.

Beyond the comedy, Seven Moons is a work of staggering literary ambition, and the result of eight years of painstaking work. Despite the runaway success of his first book, Chinaman: The Legend of Pradeep Mathew, which he had initially self-published (an Indian publishing house later picked it up), Karunatilaka struggled to find publishers for Seven Moons in the West. He is undoubtedly a writer who rejoices in complex narratives. But Sri Lankan stories are often a hard sell on the global market; whenever a local storyteller attempts to take their work to the world, the world asks why it should care.

No publisher is likely to turn down Karunatilaka now, just as the island is unlikely to ever cease providing inspiration. He deserves every accolade; we deserve his lampooning.

-Andrew Fidel Fernando is a Colombo-based journalist and writer, is the author of Upon a Sleepless Isle: Travels in Sri Lanka In Bus, Cycle and Trishaw

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.