’90 Days’ is a gripping story of the hunt for Rajiv Gandhi’s killers

Anirudhya Mitra provides the most comprehensive account of the biggest manhunt launched in India – and how the LTTE's role was detected

By M.R. Narayan Swamy

The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) may well have gotten away with the horrific assassination of Rajiv Gandhi but for Velupillai Prabhakaran’s insistence to see still or video images of the final moments of the Indian prime minister.

If those tasked with masterminding Gandhi’s killing had not hired a photographer, Haribabu, and if only his camera had perished along with him in the ball of fire that consumed the former Indian prime minister, the investigators may have run into a wall they would have found near impossible to penetrate.

Unfortunately for the LTTE, the camera miraculously survived the heat and explosion at Sriperumbudur on May 21, 1991, and its 10 clean images ended up giving the security agencies an invaluable close look at the key assassins gathered at the election rally – all of whom saw Gandhi getting blown into smithereens.

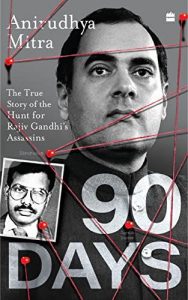

Journalist-author Anirudhya Mitra, who extensively reported on the sensational assassination and the subsequent biggest manhunt in India, in 90 Days: The True Story of the Hunt for Rajiv Gandhi’s Assassins has come up with a fascinating, gripping and the most comprehensive story of the hunt for those who meticulously planned and executed Gandhi’s brutal end. Mitra’s account reads like an electrifying and enthralling thriller. I finished the book in one go.

Journalist-author Anirudhya Mitra, who extensively reported on the sensational assassination and the subsequent biggest manhunt in India, in 90 Days: The True Story of the Hunt for Rajiv Gandhi’s Assassins has come up with a fascinating, gripping and the most comprehensive story of the hunt for those who meticulously planned and executed Gandhi’s brutal end. Mitra’s account reads like an electrifying and enthralling thriller. I finished the book in one go.

Mitra, who worked in India Today at the time of the assassination, tapped all his contacts in the security agencies – and built up new ones as he sailed along – to realize that the special investigation team (SIT) headed by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) officer D.R. Karthikeyan and his colleagues were up against an enemy that was ruthless, cold-blooded, superbly efficient and always a step ahead of their pursuers until a day dawned when they had no place to run.

The broad outlines of Gandhi’s assassination are well known: Afraid that the Congress leader was on a comeback trail, Prabhakaran and his intelligence chief Pottu Amman took the audacious decision to finish him off. The man chosen for the job was Sivarasan or the ‘One Eyed Jack’ (he had lost an eye in a battle with the Sri Lankan military) – who had in 1990 planned and overseen the killing of K. Pathmanabha, leader of the anti-LTTE Elam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front (EPRLF) group – and many of his colleagues in Chennai and escaped safely to Jaffna. After setting up safe houses in Chennai, Sivarasan returned to Tamil Nadu by boat from Jaffna on May 1, 1991 with Dhanu, a young woman hand-picked to be the human bomb for Rajiv Gandhi, and others.

After a ‘dry-run’ on then prime minister V.P. Singh in Chennai, to see how well the plan would work on Gandhi, Sivarasan, Dhanu, LTTE operative Shuba and an Indian citizen Nalini (an ardent LTTE supporter) reached Sriperumbudur in a bus. Accompanying them was Haribabu, who had no clue about what was to happen that day. His job was to photograph Dhanu garland Gandhi. She did that and bowed, pretending to touch his feet but did not get up. She activated the toggle switch of her hidden bomb, triggering a deafening explosion that killed Gandhi, herself and 14 others.

This story and even a bulk of the information in the book may be known in varying degrees. But what hooks you is the way Mitra connects, one after another, the seemingly endless dots in the macabre plot, pouring in a vast amount of details but with a writing style that doesn’t bore. Some accounts, including how hours of tension-filled waiting led to the arrests of Nalini and her LTTE assassination squad member and lover Murugan, make for dramatic reading.

Mitra exposes how foolishly the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), which should have actually known better, claimed that the LTTE could not have killed Gandhi – and said so to Prime Minister Chandra Shekhar. RAW officials were insistent despite mounting evidence to the contrary as the investigation progressed. It was only when the tell-tale photographs taken by Haribabu (the photographer mentioned above) became public that the RAW had to admit it had blundered.

Despite many wrong leads and some mistakes on its part, the SIT investigation sent the LTTE running in circles in Tamil Nadu, a state the deadly group had come to take for granted. Investigators, who included some of the best brains in the country’s security forces, made rapid progress, making one important arrest after another, skilfully connecting many jigsaw puzzles. There were many pressures on Karthikeyan and plenty of criticism too on various grounds. But what turned into a real headache was the inability to catch Sivarasan, the man who masterminded the assassination and who was at the Sriperumbudur rally ground pretending to be a journalist.

Eventually, when Sivarasan was cornered in a Bengaluru suburb, all his six colleagues (including Shuba who too witnessed Gandhi die) took cyanide and died in LTTE kamikaze-style while the mastermind shot himself dead. It went to the credit of the LTTE and Sivarasan that he managed to elude a sweeping manhunt for three long months.

In the final drama that took place, Mitra shreds to pieces the sheer inefficiency and professional misconduct by the Indian security agencies, in particular the Karnataka Police, who turned what should have been a hush-hush operation into a public spectacle, alerting in the process Sivarasan and others and nullifying whatever slim chances the National Security Guards (armed with anti-cyanide doses) had of trying to catch the master killer alive.

Based on what some investigators and others told him, Mitra makes more than one reference to the possibility of a larger conspiracy with foreign links which the SIT overlooked.

On the strength of what little I learnt after pursuing the LTTE story from the inception of the Tamil insurgency in 1983 till the Tigers were militarily crushed in 2009, I can safely say that the copyright for the assassination was the sole property of Prabhakaran and Pottu Amman. The LTTE was puritan to the extent that it would not kill any high-profile figure on anyone’s order or request, whatever the allurement.

It is one thing to speak of vague generalities about threats to Rajiv Gandhi; when it came to the LTTE, it worked on a strict need-to-know basis. There can be no question of even Sivarasan being linked to any foreign intelligence agency because this would have earned him a death sentence in the LTTE. Did not the LTTE have dubious links with foreign countries and entities? Sure it did; it could not have survived so long without such linkages. The LTTE had certain cocky confidence: ‘we manipulate others, no one can manipulate us.’

The killing of Rajiv Gandhi was the biggest blunder by Prabhakaran, a decision that cost him, for eternity, the invaluable support of India and the use of its land and sea for its insurgency. He probably never thought the LTTE hand would get exposed.

-M.R. Narayan Swamy is a veteran journalist and this review was originally featured on thewire.in