How Martin Wickramasinghe shaped an understanding of Sri Lanka – and South Asia

His compatriots know him as a novelist. But scholars say he must be acknowledged as a modernist intellectual, significant for the entire region

By Uditha Devapriya

The Koggala Folk Museum, located around 15 km from the southern coastal village of Galle, stands as one of the largest museums and collections of cultural artefacts in Sri Lanka. On weekdays, the parking area is almost always occupied by buses, hired by schools across the island for field trips. Depending on the time you have, a complete tour would take anywhere between an hour to half a day.

The museum seamlessly gives way from one section of artefacts to another. From Buddha images and temple murals to clay pots, kitchen implements, masks, puppets and costumes, all the way to boats, bullock carts, and fishing equipment, they provide a visual glimpse into life in 18th- and 19th-century southern Sri Lanka.

Towards the end of the tour, one comes across a house that looks no different to other rural middle-class houses from that period. Outside, an old colonial period couch offers refuge from the heat.

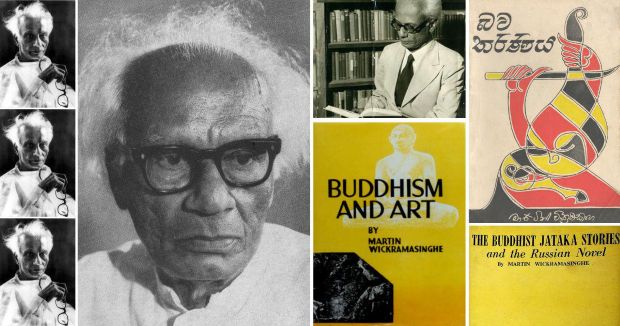

This was the house in which Martin Wickramasinghe, one of Sri Lanka’s most renowned literary and cultural figures, spent much of his childhood in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In his country, Wickramasinghe is celebrated as the definitive man of letters of modern Sri Lanka. Hardly any Sri Lankan has not read his novels, and almost no one who has not watched the film and television adaptations of his stories.

Many of these stories have been translated into English and other languages, including Hindi, Chinese, Tamil and Russian. Many more are being translated.

However, even though Wickramasinghe wrote countless essays on art, culture, literature, politics and society, he is mainly known for his fiction.

According to Jayadeva Uyangoda, Emeritus Professor at the University of Colombo, Wickramasinghe added substantially “to the corpus of knowledge about Sri Lanka to which scholars and historians like Ananda Coomaraswamy had already contributed”.

Uyangoda notes, however, that though Wickramasinghe shaped an understanding of Sri Lankan and even South Asian society, this has yet to dent popular perceptions of him as a national – even nationalist – intellectual.

Historian Shanti Jayewardene agrees. She says that Wickramasinghe is a “poorly understood” and “highly enigmatic” intellectual figure, not just in Sri Lanka but South Asia.

Leading academics in Sri Lanka and members of Wickramasinghe’s family hope that this perception will soon change. They argue Wickramasinghe needs to be acknowledged as a modernist intellectual, who was significant not just Sri Lanka, but also the region.

Two worlds

Born in 1890, Wickramasinghe had his early education in Koggala, where, under the tutelage of village teachers and Buddhist monks, he acquired a love for Sri Lankan literature – in particular Sinhala and Buddhist works. Later, he came under the sway of Christian missionaries, who in the early 19th century had established the Southern Province, specifically Galle, as a centre of their education work.

From the beginning, Wickramasinghe juggled these two worlds: Sinhalese Buddhist and Western/English.

Wickramasinghe’s father was a well-regarded local government official. His reputation gave the young boy the freedom to meet villagers and talk with them. Wickramasinghe was particularly fascinated by the natural surroundings of Koggala and the jungle beaches of Rumassala in Unawatuna, some 15 km away.

However, his father died when Wickramasinghe was quite young, and the state of his family’s finances compelled him to abandon his formal education. At the age of 16, in 1906, he was dispatched to Colombo, where he worked as an assistant to a shopkeeper. It was here that he became interested in a writing career.

By 1920, he had found employment as a journalist in one of the leading newspapers in the country, the Dinamina. But he had been writing to newspapers since 1916. While working in Colombo, he had come across Western novelists, thinkers and academics – Robert Ingersoll, Ernst Haeckel, Paul Carus and Thomas Huxley, among them.

Through these writers, Wickramasinghe discovered Charles Darwin, whose writings on evolution sparked a lifelong interest in biology. He began to subscribe to foreign journals, participate in public debates and reflect on what he read. Lacking formal education, he spent a good portion of his income on books. His personal collection, housed today in the National Library in Colombo, contains over 5,000 titles.

Although Wickramasinghe read widely in English, it was only later that he started writing in that language. He wrote extensively on Sinhala culture and Buddhism, focusing on the patterns of life in his home in the Southern Province. Through scholarly works such as Buddhism and Art, Aspects of Sinhalese Culture, Buddhism and Culture, Buddhist Jataka Stories and the Russian Novel, and Landmarks of Sinhalese Literature, he sought, as the anthropologist Sarath Amunugama puts it, to make Sinhala Buddhist culture “as perfectly valid an object of study as any other rural traditional society in the world of his time”.

The 1910s and 1920s were highly fruitful and productive decades in terms of advances in social science and anthropology, two subjects which transfixed him. When Malinowski’s Argonauts of the Western Pacific came out in 1922, Wickramasinghe read it with deep interest and saw parallels between the folk tales of the Trobriand islanders and those of the Sinhalese people in the Southern Province of Sri Lanka. Ruth Benedict’s Patterns of Culture (1934) also intrigued him, as did the works of art historians like EB Havell and Stella Kramrisch. He acknowledged his debt to these writers, particularly to Benedict, Havell and Kramrisch, whose methodologies and frameworks he adopted when assessing his own society and culture.

Wickramasinghe’s contribution as a modernist thinker in Sri Lanka, in that sense, was two-fold. First, he helped introduce Sinhalese-speaking readers to many Western writers and thinkers, including Friedrich Nietzsche, Andre Gide and Guy de Maupassant. A proponent of literary realism, he adopted some of the techniques which had been pioneered by these writers in his own Sinhala fiction.

His short stories, for instance, are filled with layers of the sort of irony that one encounters in de Maupassant’s work. Some passages in his novels are pervaded by interior and stream-of-consciousness monologues.

Second, he wrote in English on aspects of his culture and society for foreign audiences. Often, in this, he would adopt the frameworks of the leading scholars and thinkers of his time. For instance, he used American anthropologist Ruth Benedict’s classification of human cultures into Apollonian and Dionysian types. Benedict framed Apollonian cultures as being more restrained and collectivist, and Dionysian societies as being more individualist. Wickramasinghe argued that Sinhala culture, with what he saw as its emphasis on restraint, was more Apollonian than Hindu.

Wickramasinghe’s contribution here was, in many respects, unprecedented. By the time he began to write on Sinhalese culture from the 1920s, much of the serious work on that culture had been undertaken by either foreign scholars, colonial officials or members of the colonial elite in the country.

Given their social conditioning, they were too far removed from the society they tried to study. Wickramasinghe contended that this led them to misjudge Sinhala and Buddhist culture. He was especially taken up by the Sinhalese contribution to South Asian Buddhist art and argued that, though art critics like EB Havell did much to raise awareness of the subject, they overlooked and misinterpreted Sinhalese art.

Misread as a ‘nationalist’

In Sri Lanka, Martin Wickramasinghe is primarily acknowledged as a novelist, not a critic. Part of the reason that his work is not understood well is, of course, the fact that much of his writing is in Sinhalese.

However, that alone does not explain why he has been sidelined even from the pantheon of Sri Lankan intellectual figures. Wickramasinghe was a contemporary or near contemporary of several modernist artists, including the architect Geoffrey Bawa, the filmmaker Lester James Peries, the dancer Chitrasena and the painter George Keyt. Perhaps because they are more accessible, in terms of the art forms and language in which they operated, these individuals have been written about from various perspectives.

Martin Wickramasinghe, by contrast, has been mainly studied by Sri Lankan scholars. This has reinforced the perception, especially among Sinhala and Buddhist nationalist ideologues, that he was a nationalist thinker.

Like the metaphysician and art historian Ananda Coomaraswamy, he is perceived to have valorized the rural agrarian society of 19th and early 20th century Sri Lanka. In this reading, Wickramasinghe is frequently framed as a utopian and a romantic.

Because he is so associated with this ideology, even Western scholars are quick to link him to the postcolonial nationalist discourse in Sri Lanka.

However, these perceptions are refuted by a growing number of contemporary Sri Lankan social scientists, a sign that Wickramasinghe is slowly being reassessed and reappraised at home.

For instance, literary theorist and historian Crystal Baines, in her thesis on secular thought and religious nationalism in contemporary Sri Lanka, contends that Wickramasinghe’s interpretation of Buddhism was driven by a rational progressive worldview, which is hardly compatible with the thinking of nationalist ideologues today.

Two of Wickramasinghe’s grandchildren, Malin Wickramasinghe and Ishani Sinnaduray, agree. Sinnaduray in particular remembers her grandfather as being “highly critical” of conservative monks. “More than anything, he believed that religion had to work at a popular level, that it had to be accessible to people,” she recalls.

Malin Wickramasinghe, who serves as secretary of the Martin Wickramasinghe Trust – based in Nawala, a leafy suburb in Colombo – says that towards the end of his life, the more militant and right-wing sections of the Buddhist clergy fell out with his grandfather.

“Politically, he was more aligned with socialism, and I think that did not win him favour with conservative monks,” he observes.

This came out quite sharply in Wickramasinghe’s last novel, Bhavataranaya, in 1973, which explores and speculates on the early life of Siddhartha Gautama, before his Enlightenment as the Buddha. Jayadeva Uyangoda, Professor Emeritus of the University of Colombo and one of the country’s leading political scientists, compares it to Giovanni Papini’s The Story of Christ.

Like Papini’s novel and Nikos Kazantzakis’s The Last Temptation of Christ, Wickramasinghe’s Bhavataranaya depicts the life of a religious subject with unusual frankness – most graphically in a passage where Siddhartha expresses his affection for his consort, Yashodara.

The publication of the novel raised a furore in the country and scandalized audiences.

The Sri Lankan science writer and journalist Nalaka Gunawardene observes that at least one person called for the novel to be banned and its author jailed. Fortunately, “Sri Lanka was living through rational times, and the government chose not to proceed with such a drastic course of action”, Gunawardene says.

To some, the publication of Bhavataranaya and the response to it illustrated a “rupture” in the intellectual trajectory of post-colonial Sri Lanka.

“From early on, Wickramasinghe had decidedly radical views on culture and society,” Harindra Dassanayake, political analyst and commentator, observes. “Yet back then, his works were received favourably. Towards the end of his life, we can see a gradual erosion of that culture of tolerance.”

It is for this reason, he argues, that it is anachronistic to view him as a member of Sinhala nationalist circles. “He was appropriated as a nationalist figure only after his death,” Ishani Sinnaduray adds.

The problem, the historian Shanti Jayewardene says, is that Sri Lankans tend to celebrate Wickramasinghe so much “that they do not know what influenced him and guided him”. For instance, she notes, even though his memoirs reveal what he was doing in Colombo, “we do not know why he chose to read rationalist texts and why they appealed to him”.

Framing him along these lines to explore his radicalism, as both writer and critic, reveals his contribution to modernism in Sri Lanka and South Asia.

In recent years, there has been much interest in the modernist thinkers and artists of Sri Lanka. Jayewardene’s study of Geoffrey Bawa and SinhaRaja Tammita-Delgoda’s study of George Keyt unearth the parallels and differences between the trajectories of modernism in Sri Lanka and India.

I myself tried to explore these trajectories in relation to Wickramasinghe’s work at a lecture I delivered at the India International Centre in New Delhi on November 20.

Clearly, however, more needs to be done.

The Martin Wickramasinghe Trust has commissioned several translations of his work, including of Bhavataranaya, which is a difficult text to render into English. Other books, including his essays on Buddhism and his autobiography, are also being translated.

“He was a self-made man,” Maninda Wickramasinghe, another grandson, told me. “I think that would appeal to many people. But it is a story we have yet to chart in full.”

-Uditha Devapriya is a writer, researcher and columnist based in Sri Lanka who has been published in various platforms on a range of topics, including art, culture, history and foreign policy. This article was originally featured on scroll.in

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.