The emergence of an independent Bangladesh 49 years ago

And regional politics that had India literally fighting the battle on its own

By P. K. Balachandran

COLOMBO – December 16, 2020 marks the 49th anniversary of the end of the war in East Pakistan which led to the emergence of an independent Bangladesh. Joint operations by the Bangladeshi guerrilla force, the Mukti Bahini and the Indian armed forces ended Pakistani rule in 14 days.

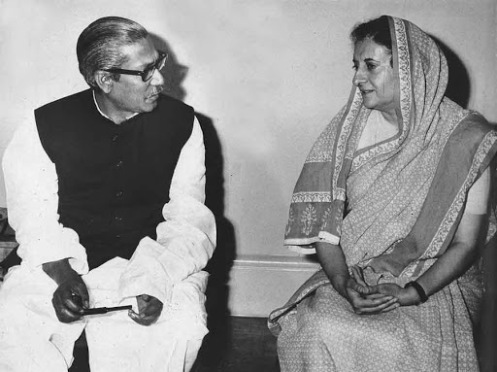

India played a vital role in bringing this about, but the Indira Gandhi government in New Delhi had to traverse a very hard road, strewn with expected and unexpected obstacles.

From March 25, 1971, atrocities described as “genocide” by the Sunday Times were being perpetrated by the Pakistani Army. Eight million Bengali refugees had poured into India. The Western media was carrying grizzly accounts of what was happening in East Pakistan, stirring the conscience of people across the globe. But even so, India was experiencing great difficulty in getting the Big Powers and even the Non-Aligned countries, to prevail upon the military rulers of Pakistan to cease military operations; talk to East Pakistani Bengali leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman; come to a solution acceptable to the struggling Bengalis of East Pakistan and create conditions for the return of refugees.

The saga of the mobilization of world support for India’s goal is related with incisiveness and in fascinating detail by historian Srinath Raghavan in his book 1971: A Global History of the Creation of Bangladesh (Permanent Black 2013). Raghavan’s finding is that Bangladesh’s creation was not a natural certainty but the end product of global and regional politics. Going to war to send back the refugees or get Bengalis their rights in Pakistan was not India’s first option as it would have meant fighting three times in nine years (with China in 1962, and with Pakistan in 1965 and 1971).

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi desperately needed global support to check Pakistan’s military ruler Gen. Yahya Khan. Arming of Pakistan had to be stalled to prevent it from attacking India on the plea that the Bengali resistance fighters were operating from India. Though the Non-Aligned countries had little or no resources to help India, their moral backing in international forums would go a long way to justify India’s stand on the issue.

But all these countries saw the developing situation differently from how India did. Each had its own interests, ideological predilections and world view. The colossal nature of the human rights violations in East Pakistan did not move governments even though human rights organizations, the intelligentsia, and the media in the West understood what was going on in Bangladesh and in the Indian refugee camps.

United States

The then US President, Richard Nixon, and his National Security Adviser, Henry Kissinger, were, as expected, very hostile to India. They were pro-Pakistan and pro-China to boot, the latter as US had made up with Communist China by then. India feared a China-US gang up against it. When the US came to know of India’s military mobilization on the Eastern border, Kissinger described Indians as “bastards, the most aggressive goddamn people”, and urged cutting off economic aid to precipitate a “mass famine” in the country.

However, the US refrained from militarily helping Pakistan retain its Eastern wing. Raghavan says one of the reasons for this was the State Department and the CIA differed from Kissinger and felt the main issues were the huge refugee influx and the absence of a political initiative involving the main Bengali party, the Awami League and its leader Sheikh Mujib, who was incarcerated in Pakistan.

However, in the final stages, due to dissension between New Delhi and the Bangladesh government-in-exile, the US found a dissenter in ‘Foreign Minister’ Kondekar Mushtaque Ahmad, who did not want an India-Pakistan war but an independent Bangladesh attained with US support. But Indian intelligence nipped the nexus in the bud. As time seemed to be running out, India began preparations for war. The US took an aggressive posture in response, but did not act.

Western Europe

Western European governments were equivocal on the issue and were suggesting that India and Pakistan exercise restraint and avoid war at all costs. But the coverage of the atrocities in East Pakistan in their media and the impact this was having on their human rights oriented populations, led to a small change in their official stance. But they never became active participants in efforts to make Yahya Khan see reason and shed his hard line.

The West was trying to make the East Pakistan issue an India-Pakistan bilateral problem, while India maintained that it was a West Pakistan-East Pakistan issue which was having unbearable fallout in India. In India’s view, the only solution was to persuade Islamabad to talk to the Bengali leadership, which had popular acceptability, namely, the Awami League headed by Sheikh Mujib.

USSR

The USSR feared China (with which it had fallen out quite badly in the late 1960s) would benefit from a troubled or liberated East Pakistan, and felt China had connections with Bengali leftists who were in the forefront of the Bangladeshi liberation struggle. It was also interested in weaning Pakistan away from China. Towards this end, Moscow soft pedalled the atrocities in East Pakistan and even sent some military equipment to Pakistan. It also explicitly supported the preservation of Pakistan’s territorial integrity. In its dealings with New Delhi, Moscow urged restraint while assuring that it was urging Islamabad to be reasonable on the Bengalis’ demands. But India objected to Moscow’s equating it with Pakistan and strongly opposed sending weapons to Pakistan. However, eventually, the USSR thought it prudent to cast its lot with India and entered into a treaty with it, which helped India fight the war.

China

China’s pro-Pakistan utterances created fears in India about a two-front war. China endorsed Pakistan’s charge that the problem in East Pakistan was instigated by India. However, China also advised Pakistan to find a negotiated solution to the Bengali question. Suddenly, Chairman Mao personally sought friendship with India. He did not militarily aid Pakistan when the war broke out. According to Raghavan, Mao was restrained because he was facing unrest in the top echelons of the Peoples’ Liberation Army.

Non-Aligned countries

India expected the Non-Aligned countries to come to its help but then Ceylon, Egypt and Yugoslavia took stands that did not suit India. Ceylon under Sirima Bandaranaike offered to hold a small conference in Colombo to chalk out a solution but she too saw the developments in East Pakistan as being part of India-Pakistan rivalry ignoring the real issue which was the denial of political rights to the Bengalis and the crackdown unleashed on them. Moreover, Bandaranaike had allowed Pakistani military planes to land in Colombo en route to East Pakistan, which India considered an unfriendly act especially because India had helped her crush a Left wing insurrection in the same year.

Anwar Sadat, who was ruling Egypt, was trying to establish himself in the Arab and Islamic worlds as an Islamic leader, and as such, thought it fit to side with Islamic Pakistan. Sadat did not plead the case of the Bengalis but urged both India and Pakistan to be restrained. Iran’s King Reza Shah Pehlavi blew hot and cold but it was clear that he was pushing the Pakistani line.

Israel

Unable to make headway in the Non-Aligned and Islamic worlds, India entered into a secret deal with Israel, which was eager to gain diplomatic recognition and its agents helped India acquire weapons which came in handy in the war.

Meanwhile, Gen.Yahya made it clear that he would not negotiate with Sheikh Mujib and began preparations for war. India had no option but to respond in kind.

-P K. Balachandran is a senior Colombo-based journalist who in the past two decades, has reported for The Hindustan Times, The New Indian Express and the Economist