By Sasha Von Oldershausen

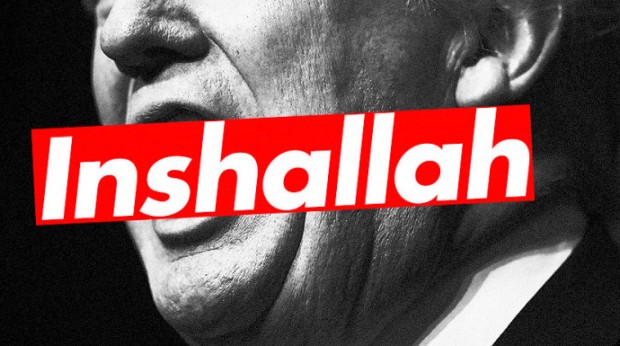

When Joe Biden dropped the Arabic phrase ‘Inshallah’ in the first presidential debate last month, Muslim Twitter lost it. Inshallah, which means “if God wills,” can be a double-edged sword, equal parts sincere and savage. I grew up with a Muslim Iranian mother, and having spent time in Iran, where Farsi speakers also use the term handily, I recognized Biden’s deployment as a mockery of his opponent, President Donald Trump.

Responding to a question about his tax returns, which he has refused to make public, Trump claimed that he’d paid millions of dollars to the government in 2016 and 2017. “And you’ll get to see it,” Trump said. “When?” Biden retorted. “Inshallah?” Translation: We’re not going to see it.

It wasn’t the first time the Democratic presidential nominee used the saying in public. Earlier this year, at a campaign event in New Hampshire, Biden employed the term with the same level of irony when talking about Sen. Bernie Sanders’ ‘Medicare for All’ platform. “It’s going to take at least four years to pass it. Inshallah,” Biden said, and then, in case his audience missed it, added: “You’re not going to pass it.”

On both occasions, Muslim and Arab Americans responded. Some criticized Biden for tactically employing the term to appeal to Muslim voters, despite his history of endorsing US military interference in the Middle East as a senator and vice president. Others loved to see it, especially after years of anti-Muslim rhetoric and policy coming from top government officials, including at the White House.

In 2016, the Swet Shop Boys, a rap duo formed by Himanshu Suri and Riz Ahmed, released the song ‘T5’, which opens with the verse: ‘Inshallah, mashallah, hopefully no martial law’. The lyric calls attention to the profiling Muslim and Arab Americans face in this country for neutral expressions of their culture. (In 2016, for instance, a University of California, Berkeley student was removed from a Southwest Airlines flight when a passenger overheard him say “inshallah” in a phone call.)

The following year, those lines became an anthem for protesters of the Trump administration’s travel ban, which prevented people in several Muslim-majority countries from obtaining US visas.

Suri recalled watching a video of demonstrators outside LAX chanting the verse. “It was a cool feeling,” Suri said. “I think when you make music, you don’t necessarily think of it as protest music, even though that’s what it very clearly is.”

The phrase crops up elsewhere in pop culture, too, including in Drake lyrics and, somewhat imprecisely, on Lindsay Lohan’s Instagram feed. Its overall usage in the English lexicon has more than quadrupled in the last three decades, according to Google’s Ngram Viewer. Its steepest increase corresponded to the years after 9/11, when President George W. Bush declared a global ‘War on Terror’ that would lead to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

From 1998 to 2002, enrolment in Arabic-language courses across the nation nearly doubled. “Back in the day, you would take Arabic because you were a weirdo that was interested in medieval texts, pious texts, maybe modern literature,” said Nader Uthman, a professor of Arabic language and literature in NYU’s Middle Eastern Studies department. “Generally speaking, classes had two or three people in them,” he said. Nowadays, Uthman said, his Arabic classes are often filled with students hoping to become journalists, diplomats and aid workers.

The term would also be embraced by the military, whose ranks favoured its colloquial meaning as a kind of deferral. “When you talk to US soldiers about the possible success of ‘the surge,’ you’d be surprised how many responded with ‘inshallah,’” an Army officer wrote in 2007 in a note to The Washington Post’s military correspondent Tom Ricks.

Some soldiers picked up the term organically or from interpreters, but Dustin Jones, a former Marine who completed a tour in Iraq in 2009, and another tour in Afghanistan in 2010, had taken Arabic and Pashto language classes before his deployment (thanks to his high scores on the ASVAB, an aptitude test developed by the Department of Defence). The term inshallah, he said, reminded him of a phrase his Catholic great-grandmother used to say: “A man is blessed who does his best and leaves the rest to God.”

There’s no precise analogue for ‘inshallah’ in English, or any other Western language for that matter. As of this year, Germany has an entry for the phrase in the Duden dictionary, as does Merriam-Webster. Perhaps, if God wills it, the Oxford Dictionary will call it the 2020 word of the year. For what term better captures this moment?

-New York Times