Controversial Mauritius ship to tow broken supertanker New Diamond

By Nishan Degnarain

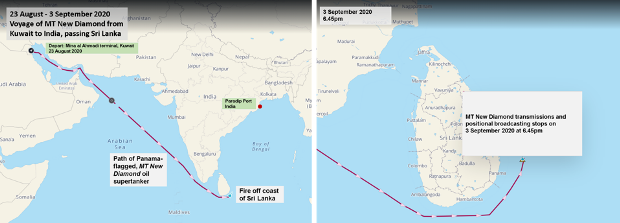

The Panama- flag oil supertanker that had an explosion off the coast of Sri Lanka earlier this month, the MT New Diamond, is being helped by a controversial support vessel that led the operation to deliberately sink a large, Japanese iron ore vessel Wakashio in the coastal waters of Mauritius last month.

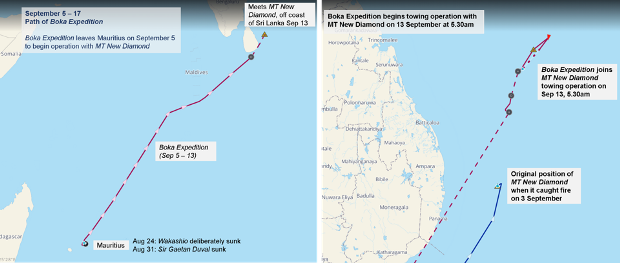

Satellite analysis by global maritime analytics firm, Windward has revealed that the Malta-flagged fire-ship, Boka Expedition, sailed from the scene of the controversial scuttling of the Wakashio on August 24, an event that sparked national protests in Mauritius and outside its embassies around the world. Photos taken by the Mauritian Coastguard were shared but the location of the sinking was never disclosed.

Within days, a second vessel sunk in Mauritian waters, the Sir Gaetan Duval with the loss of four crew on August 31. Satellite analysis from Windward reveals that the Boka Expedition was involved in the Search and Rescue operation there too.

Five days later, the Boka Expedition then sailed straight to the MT New Diamond that was on fire for several days off the coast of Sri Lanka. The complex mission to save the MT New Diamond took almost a week and involved a dozen ships from several nations.

The Panama-flagged oil supertanker was carrying two million barrels of crude oil from Kuwait to India when an onboard explosion 40 miles off the coast of Sri Lanka killed a crew member and put the entire Southeast coastline of the large Indian Ocean island at risk.

SMIT Salvage has been involved in the salvage operation in Mauritius with the Wakashio since the start, and the same company is also engaged in the operation for the MT New Diamond that is now off the coast of India and unable to be towed into a port.

The Malta-flagged Boka Expedition had been singled out by Greenpeace, who identified several international laws that may have broken with its role in the sinking of the Japanese oil spill ship the Wakashio.

When the front section of the Wakashio was being towed from the coast of Mauritius on August 19, it was no longer a boat. It had already been designated a total constructive loss. So that means the vessels towing this garbage (which the front half of the Wakashio was), were liable for any laws that would have been broken in its disposal (e.g., the definition of Marpol Annex V Laws). Given that the weather was calm at the time of the scuttling, it was unclear why such an operation was needed.

If the captain of the Wakashio was arrested for negligence of duty, then why haven’t the captains of the two vessels who towed and dumped the 300 metre long broken hull in Mauritian waters? As captains, they should know all the laws of the seas.

Greenpeace letters

In a letter written on August 25 to the Malta maritime and environmental authorities, Greenpeace asked serious questions about two Malta-flagged vessels’ role. Malta is a signatory to several ocean pollution laws. In the letter to the Malta Authorities, Greenpeace said,

“The MV Wakashio is being towed to its planned sinking place by several ships – among them two Maltese-flagged vessels, the Boka Summit and the Boka Expedition. As a party to the London Convention (1972), the Republic of Malta is required to prohibit and prevent its vessels from dumping waste including vessels at sea, except under the limited conditions recognized in the Convention.

According to Article III.a.2 of the London Convention (1972), the deliberate disposal of vessels at sea is considered dumping. In accordance with Article IV.1.a), read together with paragraph 11(d) of Annex I, the dumping of ships at sea is forbidden, unless “material capable of creating floating debris or otherwise contributing to pollution of the marine environment has been removed to the maximum extent”. Even if such cleaning has taken place, a permit must first be issued in accordance with the provisions of the Convention. Given how fast the decision was made between breaking the ship and the start of towing we find it highly unlikely that any and all polluting content was removed, let alone a thorough permitting process.

In accordance with Article V.1, dumping without a permit is permissible only in a force majeure situation, when it is “necessary to secure the safety of human life or of vessels, aircraft, platforms or other man-made structures at sea.” Since the crew of the MV Wakashio had already been evacuated, and the vessel had broken in two, it is clear that dumping no longer served to secure human life or the vessel, and a permit was required.”

The Boka Expedition and the Boka Summit were responsible for dragging a wreck off Mauritius’ coral reef, causing untold damage, and dumping the oil in an undisclosed location in the Indian Ocean.

Satellite tracking had revealed that the Boka Expedition was the lead vessel in this operation and was involved in dragging the wreck toward Antarctica.

Silence from UN shipping agency

Despite international condemnation from environmental organizations Greenpeace and Sea Shepherd, the UN shipping regulator – that sets and proudly boasts about these laws – has remained silent on the issue. It is noticeable that the Secretary-General has issued statements about the Beirut Port incident and the Gulf Livestock sinking, but not the incident in Mauritius where the IMO were the lead co-ordinating UN agency.

This has been as footage emerged of the IMO representative in Mauritius – who was the main UN coordinator of the oil spill response operation – giving a detailed account of the decision to sink the Wakashio.

At a press conference sitting next to Mauritius’ Commissioner of Police on August 21, IMO representative, Matthew Sommerville did not disclose the location of the sinking of the vessel but said that France had given input into the decision.

This implies there was French support to sink the 300-metre- long front section of the Wakashio without taking the appropriate pollution precaution as international laws require.

Were international laws broken in sinking the Wakashio?

At least five international laws appear to have been broken with the sinking of the Wakashio:

- International laws on the safe disposal of Ballast Water Pollution

The Wakashio’s hold would have been full of ballast water – almost 200,000 tons. This water would have originated from a different location (likely Asia) and in all likelihood contained many invasive larvae, bacteria and other non-native and harmful species to Mauritius’ unique coral reefs. This pollution is more than 50 times the amount of oil that was being transported, is extremely dangerous biologically and is a serious legal offence.

The full name for this international law is called the International Convention for the Control and Management of Ships’ Ballast Water and Sediments (or BWM Convention for short), which came into force in 2004.

In his opening address to the Conference introducing the Convention on Ballast Water at the IMO’s London Headquarters on February 13, 2004, the Secretary-General of the IMO stated that the new Convention would represent a significant step towards protecting the marine environment for this and future generations. “Our duty to our children and their children cannot be over-stated. I am sure we would all wish them to inherit a world with clean, productive, safe and secure seas – and the outcome of this Conference, by staving off an increasingly serious threat, will be essential to ensuring this is so”.

- Regulations on Anti-fouling Materialsused on vessel hulls

This law came into force in 2008 and its full name is the International Convention on the Control of Harmful Anti-fouling Systems on Ships (or AFS Convention for short).

Since the towing of the bow of the Wakashio began on August 19, neither the ship owner, Nagashiki Shipping, the company responsible for the salvage operation, SMIT Salvage, or the UN Shipping Agency responsible for these laws have responded to questions from national or international media on violations of anti-fouling materials on the Wakashio.

Article 12 of the AFS Convention that covers Violations is very clear on the evidence that needs to be submitted and penalties for any violation.

“Any violation of this Convention shall be prohibited and sanctions shall be established therefore under the law of the Administration of the ship concerned wherever the violation occurs. If the Administration is informed of such a violation, it shall investigate the matter and may request the reporting Party to furnish additional evidence of the alleged violation.”

On penalties, the law is clear. “The sanctions established under the laws of a Party pursuant to this article shall be adequate in severity to discourage violations of this Convention wherever they occur.”

The Convention also states that “any violation of this Convention within the jurisdiction of any Party shall be prohibited and sanctions shall be established therefore under the law of that Party. Whenever such a violation occurs, that Party shall either: (a) cause proceedings to be taken in accordance with its law; or (b) furnish to the Administration of the ship concerned such information and evidence as may be in its possession that a violation has occurred.

Evidence can be submitted within 12 months of the event occurring, which in the case of the Wakashio was on August 24, 2020.

According to statements issued by the Government of Mauritius, the entire salvage operation since the Wakashio hit the coral reefs of Mauritius on 25 July 2020, was under the supervision of the vessel owner, Nagashiki Shipping, its insurer, Japan P&I Club as well as the appointed salvors, SMIT Salvage.

In a statement, on 26 July 2020, the Prime Minister of Mauritius stated that the owner of the vessel and SMIT Salvage Pte Ltd signed the Lloyds Standard Form of Salvage Agreement (LOF). “Under this Salvage Agreement, the Salvage Team is responsible to salve the vessel and take the vessel to a place of safety. The Salvage Team has the environmental obligation to use their best endeavours to prevent or minimize damage to the environment while performing the salvage services.”

- Laws on the Environmentally Sound Recycling of Vessels

After facing criticism for the environmental and safety standards of how vessels were being disposed of at the end of life in low cost regions of India, Bangladesh and Pakistan, the IMO was forced to act. The laws that were introduced were designed to stop armadas of ships just being dumped in the ocean at the end of their life.

The Hong Kong International Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships was adopted in 2009 as a new international law to ensure appropriate end of life processes for vessels are followed.

Upon its adoption, the IMO stated how important this international law is to protect the marine environment.

“The resolution referred to the urgent need for the IMO to contribute to the development of an effective solution to the issue of ship recycling, which will minimize, in the most effective, efficient and sustainable way, the environmental, occupational health and safety risks related to ship recycling, taking into account the particular characteristics of world maritime transport and the need for securing the smooth withdrawal of ships that have reached the end of their operating lives.”

- Maritime Pollution Law (Marpol)

Maritime pollution laws are called Marpol, and each type of pollution is well defined under six sections, called annexes. Annex V concerns garbage – which the front section of the Wakashio was. Annex V would cover most of the pollution that would have been on board the 300 meter front section of the Wakashio. Violating Marpol laws is a very serious offence.

The current Secretary General of the IMO. Kitack Lim, recently gave a special address to the United Nations entitled “The Role of the International Maritime Organization in Preventing the Pollution of the World’s Oceans from Ships and Shipping

In it, he explained the importance of upholding the standards set in the Marpol Convention. “Today, the expanded, amended and updated MARPOL Convention remains the most important, as well as the most comprehensive, international treaty covering the prevention of both marine and atmospheric pollution by ships, from operational or accidental causes. By providing a solid foundation for substantial and continued reductions in ship-source pollution, the Convention continues to be relevant today.”

He described the need to protect fragile habitats from marine pollution caused by ships “MARPOL also recognizes the need for more stringent requirements to manage and protect so-called Special Areas, due to their ecology and their sea traffic. A total of 19 Special Areas have been designated. They include enclosed or semi-enclosed seas, such as the Mediterranean Sea, Baltic Sea, Black Sea and Red Sea areas, and much larger ocean expanses such as the Southern South Africa waters and the Western European waters. This recognition of Special Areas, along side global regulation, is a clear indication of a strong IMO awareness of-and total commitment to-the fundamental importance of protecting and preserving the world’s seas and oceans as vital life support systems for all peoples.”

The Secretary General of the IMO went on to say, “IMO also has a process to designate Particularly Sensitive Sea Areas (PSSAs), which are subject to associated protective measures, such as mandatory ship-routeing systems. There are currently 14 areas (plus two extensions) protected in this way, including those covering UNESCO World Heritage Marine Sites, such as the Great Barrier Reef (Australia), the Galápagos Archipelago (Ecuador), the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument (United States of America), and the Wadden Sea (Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands). This long-established practice of designating Special Areas and PSSAs fully supports the SDG 14 target to increase coverage of marine protected areas.”

This raises questions about whether the IMO had approached Mauritius about the PSSAs. Mauritius is a well known global biodiversity hotspot. Why hadn’t the IMO been proactive in designated these hotspots as protected areas?

But it also applies to the Malta-flagged Boka Expedition, that was responsible for the dumping of this waste in the ocean.

If these laws are so important to the Secretary General of the IMO, why has he not made a statement about their apparent violation with the case of the Wakashio?

- Convention on Migratory Species (CMS)

The Convention on Migratory Species could have been violated with the death of 50 whales and dolphins along the coast of Mauritius. This is a breach of international UN law under the Bonn Convention on the Convention on Migratory Species.

Whales and dolphins are strictly protected under Mauritian national law as well as several international laws (including the UN law of CITES on the transportation of any part of the whale or dolphin, including for forensic tests outside of Mauritius).

Under Article XIII of the CMW convention on Settlement of Disputes, any dispute would be subject to the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague.

The text is very clear on this, saying “i) Any dispute which may arise between two or more Parties with respect to the interpretation or application of the provisions of this Convention shall be subject to negotiation between the Parties involved in the dispute ii) If the dispute cannot be resolved in accordance with paragraph (i) of this Article, the Parties may, by mutual consent, submit the dispute to arbitration, in particular that of the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague, and the Parties submitting the dispute shall be bound by the arbitral decision.”

So if the party that caused the death of the 50 dolphins and whales are not willing to come to a settlement, this will have to be resolved at the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague.

Without enforcement, these laws are not worth the paper they are written on

Despite having set and being responsible for ensuring countries adhere to these laws, the IMO has remained silent on whether they believe any laws have been broken. Over the past months, repeated questions have been placed to the IMO on this, and no clear answer has been given.

The company brought in by the vessel insurer (Japan’s P&I Club) is Smit Salvage, who has declined to comment on this operation, and neither have their owner, Dutch giant, Boskalis.

Greenpeace and Sea Shepherd have said they will continue to apply pressure on the Malta authorities for an explanation as to whether vessels under their flag have broken international ocean pollution laws.

Those laws were written for a reason.

If countries, companies and ships can get away with ignoring these laws, even bigger questions need to be asked whether the UN shipping agency – the IMO – is fit for purpose, or whether it should be disbanded in favor of regional arrangements.

-Nishan Degnarain is a Development Economist focused on Innovation, Sustainability, and Ethical Economic Growth and this article was originally featured on forbes.com