Sinhala Buddhist Nationalism: All dressed up but nowhere to go?

By Kassapa

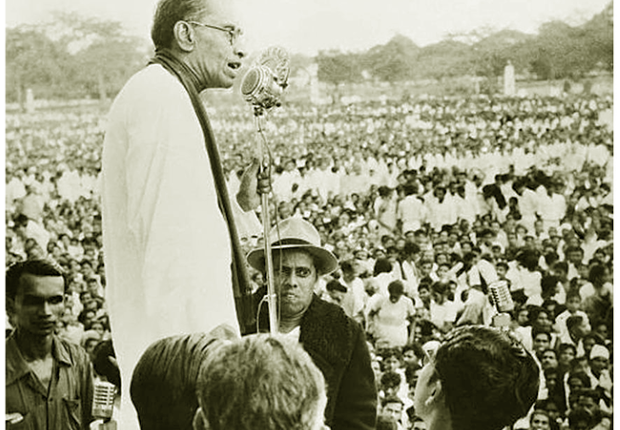

The clamour for Sinhala Buddhist majoritarianism is a slogan, a rallying call, almost as old as Sri Lanka’s post-independence history. The person who used it first with immediate success was S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike, seventy years ago in 1956. That rocketed him and his newly formed Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) into power, reducing the United National Party (UNP) to a handful of seats at that election. In a cruel twist of fate, just three years later, Bandaranaike was shot at and killed by a Buddhist monk.

Since ’56, Bandaranaike’s widow, Sirima Bandaranaike and the SLFP mostly adopted a pro-majority stance. The best (or worst, depending on how you interpreted it) example of this was the introduction of the ‘district basis’ for university admission, further alienating the Tamil community, especially. Those who could, left our shores. Others took up arms. The rest, as they say, is history.

Whatever her other faults, it was the Bandaranaikes’ daughter, Chandrika Kumaratunga, who changed the course of the SLFP into a party that was more inclusive of other communities, ably assisted by the likes of Mangala Samaraweera. Kumaratunga was all set to appoint Lakshman Kadirgamar as Sri Lanka’s first Tamil Prime Minister, but that was thwarted by Mahinda Rajapaksa, who engineered protests from the Buddhist clergy. Fearful of a backlash, Kumaratunga backtracked, Rajapaksa became Prime Minister, then President and after annihilating the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), steered the SLFP back into majoritarian mode, as it had never been before.

Under Mahinda Rajapaksa, a cabal of Buddhist monks emerged who were extremely influential. In return for various favours granted by Rajapaksa, they hailed him as the ‘saviour’ who liberated the nation from terrorism and a separate state. While Rajapaksa did give unflinching political leadership to the war effort, which his predecessors failed to do, it came at a price: a blank cheque to the Rajapaksa family to fashion their own kleptocracy that led to the country’s economic ruin, which manifested under Gotabaya Rajapaksa in 2022.

Throughout all this, the UNP was the more moderate party, inclusive and tolerant of non-majority communities, often forming alliances with them at elections. Despite the many misdemeanours of Ranil Wickremesinghe, he cannot be accused of fostering racism. In fact, he was mercilessly pilloried by the Rajapaksa-led coalitions for ‘selling the country’ to the LTTE, which probably cost him a presidential election victory in 2005.

A look at election statistics during this time makes interesting reading: the North and sections of the East voted for Tamil political parties. The votes of the South, being the vast majority and therefore the determinant of who wins elections, often endorsed the party which ran the majoritarian sentiment, the exceptions being in 1994 and 2015. When he was defeated in 2015, Mahinda Rajapaksa clung to his windowsill in Medamulana and bemoaned the fact that he had been defeated due to the resounding majorities secured by Maithripala Sirisena in Tamil-speaking areas.

This is why the 2024 election marked a paradigm shift in Lankan politics. The National Peoples’ Power (NPP) swept the board, obtained well over a two-thirds majority, but most importantly, gained representation in the North and East as well. It may have been an unprecedented situation, triggered by the mass uprising, and will possibly revert to the status quo at the next election. Nevertheless, it took everyone by surprise. Since then, the NPP and especially President Anura Kumara Dissanayake have been repeatedly saying that there will be no more room for racist politics in the country.

As if on cue, enter Namal Rajapaksa and his now small group of acolytes. Instead of thinking anew, he is offering the same tired slogans that his father did. He has also begun to sound the death knell of Sinhala Buddhists under the NPP government. Singing the chorus from the same hymn sheet are the ‘usual suspects’, the group of Buddhist monks who were his father’s followers, with perhaps the addition of a few younger faces such as Balangoda Kassapa, now (in)famous for planting a Buddha statue in the middle of a conserved beach area in Trincomalee and being remanded as a result. Add to this the cacophony from the likes of veterans such as Muruttetuwe Ananda of nurses’ trade union fame and Walawahengunuweve Dhammarathana in Mihintale, and we have the perfect recipe for Namal Rajapaksa to return in 2029 to do once again what his father did: save the nation, not from terrorists but from the ‘atheist’ NPP.

What is surprising- and disappointing- is that members of the Samagi Jana Balavegaya (SJB)- including its leader Sajith Premadasa have chosen to follow the same strategy. They don’t seem to have realized that the Sinhala Buddhist niche – as minute as it is now- is an audience that has well and truly been captured by the Rajapaksas, and by shouting the same slogans as they do, they are only alienating themselves, both from moderate mainstream majority community voters as well as those from other communities.

It is not surprising that Namal Rajapaksa hasn’t changed his strategy. This is what he knows best, and he probably knows no better. What is profoundly disappointing is that Premadasa is choosing to do the same, surrounded as he is by the Hakeems and the Ganesans, the Digambarams and the Badurdeens.

There is evidence that nationalistic or blatantly racist slogans don’t gain the kind of traction that they did during Mahinda Rajapaksa’s years, maybe partly because of the absence of a terrorist war. The drama in Trincomalee, where Balangoda Kassapa was threatening a fast unto death, hardly raised an eyebrow. No one rallied around him, and very soon the event was buried deep in the news cycle. In that sense, the Sri Lankan electorate has matured, and we hope it stays that way, come 2029.

It is said that those who do not learn from history are condemned to repeat it. Or, to put it more simply, the same experiment, repeated over and over again, yields the same results. It is a pity that the country’s two main opposition party leaders- both presidential offspring, to boot- do not realize this.

-This article was originally featured on counterpoint.lk

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.