Indefensible pardons

By N. Kannan

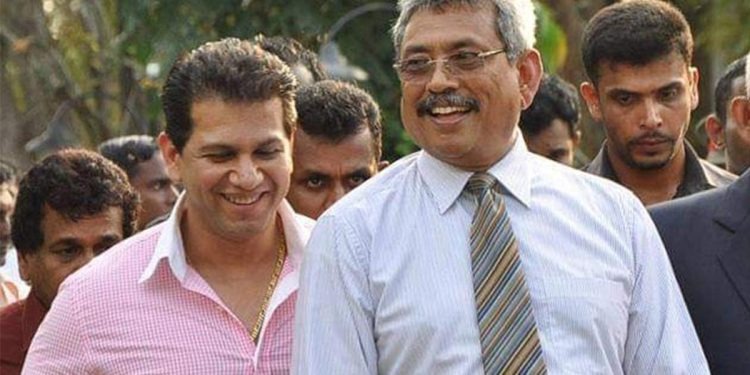

The Supreme Court in a historic judgment earlier this month ruled that the special presidential pardon granted by Gotabaya Rajapaksa to Duminda Silva, a death row prisoner, was arbitrary and legally invalid.

The judgment is the second blow to the fallacious belief that law and justice will tolerate all decisions taken by the executive president.

In October 2018, then-President Maithripala Sirisena, in a sudden move, sacked Ranil Wickremesinghe and appointed Mahinda Rajapaksa as the Prime Minister. He then went on to order the dissolution of Parliament and called for snap elections leading to a constitutional crisis.

The Supreme Court, hearing the petitions filed challenging the undemocratic action, ruled President Sirisena’s decision to dissolve Parliament and call for snap elections was unconstitutional.

Until then, the idea was that a president had the power to do just about anything. The Supreme Court ruling reversed that situation. The dissolved Parliament was reconvened and Ranil Wickremesinghe was again sworn in as Prime Minister.

That was one of Sirisena’s inglorious moves that tainted his presidency.

In the recent landmark judgement, the Supreme Court ruled the former president had not followed proper legal procedure in granting a presidential pardon, one of the special powers vested with the president of the country.

It is interesting to note that the Supreme Court ruling against the dissolution of Parliament was given when Sirisena was still in office, but the presidential pardon given by Gotabaya Rajapaksa was invalidated when he is no longer president.

One can’t help but wonder whether the Supreme Court would have delivered a judgement overturning the presidential pardon if Gotabaya Rajapaksa had been in power.

However, the Supreme Court’s decision to suspend Duminda Silva’s presidential pardon pending a verdict came at the end of May 2022 when Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s position was increasingly vulnerable. So Duminda went back to jail.

The two Supreme Court judgements showcase both Maithripala Sirisena and Gotabaya Rajapaksa, to have misused their presidential powers.

Gotabaya’s decision to grant a presidential pardon to Duminda Silva was purely political and was based on personal interests and discretion. The Supreme Court has clearly pointed out that he did not adhere to proper legal procedures in granting the pardon. He had not followed the advice of the Attorney General in this regard, and as the Supreme Court has also confirmed, he had been determined to execute his decision, ignoring all legal advice.

Next, in the affidavit submitted on behalf of Gotabaya Rajapaksa, the former president had mentioned he granted a pardon to Duminda Silva in the national interest, but not specified what the national interest was. Pointing this out, the Court had questioned what national interest was being secured in granting a special presidential pardon to Duminda Silva. No written documents related to pardon and release had been submitted to the Court.

On the whole, Gotabaya Rajapaksa had acted in a manner disregarding law and justice, using his presidential powers arbitrarily. His only goal had been to secure the release of Duminda Silva, who is close to the Rajapaksa family, and the country’s law, the Constitution, and the high responsibility given to him through it, were not important to him.

He was brought to power on a campaign promise of ensuring national security and safeguarding the country. However, there was nothing patriotic about his decision to grant Duminda Silva a presidential pardon.

Patriotism is not only about making decisions to ensure the security of the nation, it is also equally important to abide by the Constitution, Parliament and the Judiciary, which are the pillars of democratic governance. In this context, Gotabaya Rajapaksa is neither patriotic nor has respect for the nation.

He lost his patriotism when he gave priority to family interests.

And the Duminda Silva pardon is not an exception. Within the short period of his rule, Gotabaya also granted a controversial presidential pardon, during the lockdown of the COVID-19 epidemic, to army officer, Sergeant Sunil Ratnayake, who was found guilty and sentenced to death in the Mirusuvil massacre case, where eight internally displaced persons were murdered.

In Ratnayaka’s pardon too, Gotabaya did not follow proper procedures. The case against the pardon is still pending in the Supreme Court.

And it is not just Gotabaya Rajapaksa who abused his powers of presidential pardon. His predecessor Maithripala Sirisena, in the final days of his term, also pardoned Jude Jayamaha, a death row prisoner convicted of killing his teenage girlfriend at an apartment block in Colombo. On securing his freedom, Jayamaha immediately fled the country. The case filed against the presidential pardon is still pending.

Many presidents in power have used the privilege of presidential pardon. Ranil Wickremesinghe, who is now in power, has also released many people under a presidential pardon. However, there are differences in the manner the pardon was used by other presidents and how Maithripala Sirisena and Gotabaya Rajapaksa used it. In particular, the pardon granted to many Tamil political prisoners, which was done after they had spent long years in prison.

However, Sergeant Sunil Ratnayake, Duminda Silva and Jude Jayamaha were all released from prison through a presidential pardon, after they had spent very little time in prison, even though they had committed crimes that were heinous enough to warrant the death penalty.

Maithripala Sirisena and Gotabaya Rajapaksa sought to abuse the executive power, and as a consequence, their pardons are being challenged today.

Wrong paradigms can lead to historical mistakes. The judgment of the Supreme Court is intended to curb such wrong precedents. And it is a good lesson as to what happens when the executive acts arbitrarily and makes arbitrary decisions.

-ENCL

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.