A tale of three leaders and their contrasting legacies

Abe’s enduring legacy, unlike Johnson’s and Rajapaksa’s, underscores the role of integrity in leadership

By Harsh V. Pant

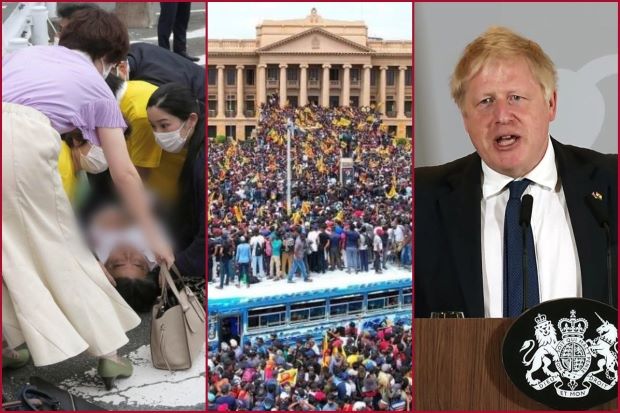

July has been a month where the fragility of political life has been all too apparent for leaders around the world. The empire of the Rajapaksas fell like ninepins, as a once-formidable Sri Lankan president had to run helter-skelter to protect himself from mob fury. People power in Sri Lanka spoke, and loudly, driving away a mighty political dynasty almost to oblivion. It will be years for this once-prosperous island nation to recover from the turmoil inflicted by the arrogance of a leader who failed to come to terms with his own shortcomings and rested on his past laurels. The carefully nurtured nationalistic credentials of the Rajapaksas could not deliver them any salvation.

In the UK, a different kind of political fall saw Prime Minister Boris Johnson deciding to step aside after insisting for weeks that nothing was going wrong for him. Warning bells had sounded long ago, but his apparent assumption that witty repartees would be enough to mellow the public mood was a mark of hubris that proved his undoing. As questions about his trustworthiness swirled around the hallowed confines of Westminster, his reputation was in tatters and a mandate that he had won in 2019 was wasted.

And then there was the shocking assassination of Japan’s former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. It is difficult to comprehend how this could happen in Japan, but the legacy of Abe, a conservative politician, is so notable that its far-reaching effects would be visible decades down the line. From domestic to regional and global spheres, few political leaders of our times have had such a significant impact on strategic trends as Abe. Even in his death, he managed to give his party a decisive victory in elections.

These three leaders from different geographies were immensely talented, as evident in their climb to pinnacles of political success and power. They all subscribed to what can broadly be called a ‘conservative’ political philosophy. But it is the fall of the Rajapaksa clan and Boris Johnson, and the continued relevance of Shinzo Abe, that underscores what makes for greatness in political life, as opposed to the mere satisfaction of personal ambitions.

As Gotabaya Rajapaksa runs from one country to another in search of asylum, his family’s fall from grace is a stark reminder of the sheer volatility of public life. It was his mismanagement of Sri Lanka’s economic crisis and his defiance of persistent calls for his resignation since March that sealed his fate. There was simmering anger against the family for months, as the island nation battled shortages of food, fuel and medicine, and the Rajapaksas who at one point were viewed as war heroes, became deeply unpopular. In terms of political identity, they had defined themselves as avowed nationalists who managed to defeat the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). But charges of corruption and nepotism dovetailed with bad policy choices, producing a cocktail of public disaffection and anger, and plunging Sri Lanka into a once-in-a-lifetime crisis. A fleeing Gotabaya is the only legacy that is now likely to endure.

Boris Johnson also came to power in 2019, riding on a colossal mandate. It was the biggest majority for the UK’s Conservative Party since Margaret Thatcher’s victory in 1987 that underlined Johnson’s credentials as the quintessential Brexiteer. His clownish charisma, slapstick political persona and witty one-liners all worked as he made his way to secure Brexit. Fed up with a never- ending Brexit debate, Britons wanted a resolution one way or another.

But beyond Brexit, Johnson hardly had a program of action. Once that theatre subsided, he himself became a spectacle. His seeming buffoonery, which at one point was a part of his carefully nurtured appeal, appeared to become an end in itself. So when the ‘Partygate’ scandal broke last December, it took weeks and formal investigations for Johnson to finally admit his mistake and apologize for breaking Covid rules during lockdowns—rules that he and his government had imposed on everyone else. As scandal after scandal nibbled away at his credibility, he remained cocooned in a world where the leader’s lack of seriousness in governance did not seem like a big deal.

But both Brexit and Covid had taken a toll on ordinary Britons. Their suffering turned into anger, as the Tories lost some of their safest seats in May. But Johnson was not done. His handling of the case against Chris Pincher, a lawmaker accused of sexual misconduct, was the last straw, raising even sharper questions over his integrity. The Tories, reading the writing on the wall, mobilized forces against him. His tenure will be looked at as one where all his ambition and intellect resulted in nothing because of a lack of discipline.

Abe too was a conservative politician, but was driven more by a higher set of ideals than merely raw pursuit of power. He was determined to restore Japan’s pride and worked hard towards it. The results have been quite dramatic. Interestingly for a conservative politician, he challenged the status quo on Japan’s domestic and foreign policy. It was his nationalistic ideals that drove him, but it was his discipline and integrity that made him one of the most remarkable Japanese politicians and one of the most significant global statesmen of our times.

This tale of three different politicians is a reminder of how the pursuit of political power in the absence of a serious governance agenda and personal integrity often consumes leaders without leaving any footprints on the sands of time.

-Professor Harsh V Pant is Vice President – Studies and Foreign Policy at Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi and this article was originally featured on livemint.com