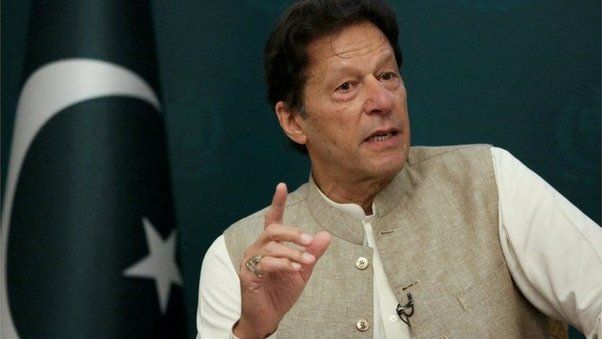

Pakistan’s Imran Khan is now the target of forces he once wielded

By Christina Goldbaum and Salman Masood

Former Prime Minister Imran Khan’s allies have been arrested. Media outlets and public figures considered sympathetic to him have been intimidated or silenced. He has been hit with charges under Pakistan’s anti-terrorism act and faces the prospect of arrest.

For weeks, Pakistan has been gripped by a political showdown between the ruling establishment and Khan, the former cricket star turned populist politician who was ousted from the prime minister post this year. The drama has laid bare the perilous state of Pakistani politics — a winner-take-all game in which security forces and the justice system are wielded as weapons to side-line those who have fallen out of favour with the country’s powerful military establishment or political elite.

That playbook has been decades in the making, and it has turned the country’s political sphere into a brutal playground in which only a few elite leaders dare play. It has also rendered the Pakistani public deeply disillusioned with the political system and the handful of family dynasties that have been at the top of it for decades.

Khan’s own meteoric rise from the fringes of politics to the prime minister’s office in 2018 was a showcase for how hard-bitten Pakistan’s politics have become: His competitors were winnowed from the electoral field by criminal charges, and by threat and intimidation from security forces. Once in office, he and his supporters employed those same tools to harass and silence journalists and political opponents who criticized him.

Even after falling out with military leaders and being removed from office this year in a no-confidence vote, the charismatic politician has been able to keep himself and his party at the centre of Pakistani politics. It is a demonstration of his ability to tap into the public’s deep-seated frustration with the political system and wield the kind of populist power once relegated to Pakistani religious leaders.

That popularity has alarmed the new government, led by Shehbaz Sharif, and the military establishment, which began picking off his supporters and have now turned the justice system on Khan himself. But the well-worn playbook seems to be doing little to keep him in check, at least so far, and some analysts fear the showdown could erupt into violence.

“The former prime minister has been accused of threatening government officials — they are serious allegations bringing the confrontation between him and the federal government to a head,” said Zahid Hussain, an Islamabad-based political analyst, and columnist for Dawn, the country’s leading daily. “Any move to arrest him could ignite an already volatile political situation.”

Since Pakistan’s founding 75 years ago, the nuclear-armed nation has been plagued by political volatility and military coups. Even in the calmest of times, the country’s military establishment has been the invisible hand guiding electoral politics, ushering its allies into positions of power and pushing away rivals.

The last prime minister to be driven from office before Khan, Nawaz Sharif — the older brother of the current prime minister — was disqualified from holding office in 2017 over corruption charges in a controversial verdict by the Supreme Court. The elder Sharif sought refuge in London, joining a long line of political figures effectively exiled from Pakistan under the threat of criminal charges.

In an echo of that political script, on Sunday (21) Khan was charged under Pakistan’s anti-terrorism act after giving a speech to thousands of supporters in the capital, Islamabad, in which he threatened legal action against senior police officers and a judge involved in the recent arrest of one of his top aides.

The charges intensified the showdown between the government and Khan, and added to a wave of reports of harassment, arrest and intimidation aimed at journalists and allies of Khan in recent weeks that many view as a coordinated effort by authorities to dampen his political prospects.

But the crackdown appears to have heightened Khan’s popularity, analysts say, bolstering his claims that the military establishment conspired to topple his government in April.

“What differentiates this moment from previous moments is the amount of sheer street power Khan has,” said Madiha Afzal, a fellow at the Brookings Institution. “And street power makes a difference in Pakistan even when it does not translate into electoral votes.”

In recent months, Khan has regularly drawn tens of thousands of supporters onto the streets, where he has lashed out at the current government and the military. The overwhelming public support has buoyed his hopes for a political comeback, and he has demanded new elections, refusing political dialogue with his rivals.

The crackdown on Khan and his supporters has intensified frustrations among young, social media savvy Pakistanis and the older generation alike over the entrenched corruption and all-powerful hand of the military in the country’s political system.

“First, they ousted him from the premiership, and now want to arrest him, ban his speeches at TV channels and harass his team members,” said Sharafat Ali, a 24-year university student sitting with his friends at a cafe in the country’s economic hub, Karachi. “But such fascist actions cannot deter the country’s people, particularly youth, from supporting Khan.”

Nearby at a busy market in the heart of Karachi, Jamshed Awan sat on his rickshaw as traffic lurched past him. Like many of his friends and neighbours, Awan has become increasingly disappointed with the country’s politics, he says.

“Most of the parts of the country have been submerged by rain-related flooding, petrol prices are on rise and inflation is on its record,” Awan said. “But instead of focusing on these issues, the government’s entire focus is entirely on Imran Khan.”

In the past two months, Khan has managed to parlay his widespread support into electoral prowess. His party, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, won sweeping victories in local elections in Punjab — a province that has often served as a bellwether for national politics — and in the port city of Karachi.

And however out of favour he may be with the military’s top brass, Khan has retained sympathizers within the ranks.

A cohort of retired military officials have attended pro-Khan demonstrations in recent months. And his chief of staff, Shahbaz Gill, went so far as to urge officers to refuse to obey their leaders during a live TV appearance, leading to his arrest and accusations that he has been trying to incite rebellion within the military.

Khan says that Gill has been tortured and sexually abused while in custody, although senior government ministers and Islamabad police officials deny that claim. In an escalation of his case late Monday (22) evening, police officers in Islamabad raided Gill’s room in parliamentary lodges, officials said.

On Monday, Khan was granted a form of bail, which is allowed in Pakistan before an arrest is made. But many fear that if Khan is ultimately arrested, it will worsen the political turmoil that has embroiled the country in recent weeks.

Khan’s supporters have warned that Khan’s arrest would be a “red line,” and as news of the charges spread Sunday night, hundreds of his supporters gathered outside his palatial hillside residence on the outskirts of Islamabad and vowed to resist arrest.

“If this red line is crossed, we will be forced to shut down the country,” said Sayed Zulfikar Abbas Bukhari, a close aide of Khan’s. “Arresting him will result in a nationwide revolt.”

-New York Times

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.