Finish the job quickly

A look back at how Dhaka ended up being the grand prize in India’s liberation war of Bangladesh

By P. K. Balachandran

India’s military campaign in East Pakistan began on December 3, 1971 and ended on December 16, with the surrender of 93,000 Pakistani troops and the creation of the independent State of Bangladesh. But the politico-military campaign did not start with such ambitious objectives. It was an unexpected combination of circumstances, both local and global, which resulted in the drastic enhancement of the objectives at the tail-end of the military campaign, points out historian Srinath Raghavan in his seminal work: 1971: A Global History of the Creation of Bangladesh.

Even while the military operations were on, the objectives were modest:(1) seizing a sufficiently large part of East Pakistan with the intention of settling the 10 million East Pakistani Bengalis who had fled to India from March 25, 1971 onwards; (2) setting up a ‘Bangladesh government’ in that area under the leadership of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman of the Awami League; and (3) securing the withdrawal of the Pakistani forces from East Pakistan to pave the way for the independence of ‘Bangladesh’.

The decision to take the whole of East Pakistan, including the capital city of Dhaka, and demand the unconditional surrender of the Pakistani forces was taken only in the last few days of the 13-day war, Raghavan says.

As per the initial plan, the Indian Army was to divide, isolate and bottle up Pakistani units in their cantonments and carry out piecemeal destruction. The capture of capital Dhaka was considered over-ambitious given that mighty rivers had to be crossed without bridges and the army itself being more attuned to set-piece battles than mobility. New Delhi also had to take into account UN and Great Power intervention if it overreached.

Army Chief Gen. Sam Manekshaw felt that if Chittagong and Khulna fell, Dhaka would automatically fall. The Eastern Command chief Lt. Gen. J. S. Aurora went along with this assessment. But the latter’s Chief of Staff, Maj. Gen. J. F. R. Jacob, insisted the entire operation would be fruitless if Dhaka, the “geo-political heart” of East Pakistan or the Bangladesh-to-be, was not captured. Jacob was over-ruled, but eventually, in the final stages of the war, everyone from top to bottom, (and also the USSR, India’s cautious ally) accepted Jacob’s theory and went headlong for Dhaka to seal a convincing victory. As former Pakistani President Gen .Pervez Musharraf pointed out, the Pakistani brass had failed to use the two mighty rivers, Padma and Meghna, to defend Dhaka. Pakistani forces were dispersed thinly across many towns leaving Dhaka undefended.

International pressure on India began on December 6, when it recognized the provisional government of Bangladesh. The US moved a resolution in the UN Security Council condemning India. The Soviets, who had by then signed a thinly-veiled military treaty with India, moved a counter resolution linking a ceasefire with a political solution on the basis of the results of the 1970 Pakistani elections, which the Awami League had won on the basis of a six-point charter of Bengali demands.This was the Indian line too.

To the dismay of US President Richard Nixon and his hawkish National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, Britain and France abstained at the UNSC. UK was then moving away from the US seeking closer economic ties with Europe. However, a UN General Assembly resolution went against India as it only sought a ceasefire and the return of the refugees avoiding references to a political solution. The non-aligned countries cold-shouldered India as they were defenders of national sovereignty.

Kissinger strongly felt that the Bangladesh issue could not be seen in isolation from global geo-political issues. He therefore opened a line of communication with the Soviets who he felt were aiding India in a bid checkmate the US and China globally. He told the USSR that if it wanted a détente with the US (the Soviets had had military clashes with the Chinese in the late 1960s and were interested in having a summit with the US) it should use its undoubted influence on India to restrain it. But the Soviet response was lukewarm if not cold.

Kissinger then tried to send arms to Pakistan, not directly, as Congress would not sanction it, but through its Muslim allies Turkey, Iran or Jordan. While Turkey and Jordan were bargaining about compensation for giving their weapons and planes, the Shah of Iran bluntly said that he would not want to annoy neighbouring USSR.

Kissinger then tried to rope in China suggesting to it that even a small movement of Chinese troops on the Sino-Indian border would rattle the Indians, given the drubbing it got in the 1962 Sino-Indian war. China issued statements condemning India’s actions. Later, it did not respond to Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s missive suggesting engagement on all contentious issues to reach a détente. However, at a public function in Beijing, Chairman Mao unexpectedly turned to Indian Ambassador Brijesh Mishra, smiled and said that the two countries must be friends. The net result was, China did not move troops to the border.

Raghavan explains this by pointing out Mao was busy at that time purging his armed forces of disloyal elements after the ‘Lin Biao affair’. War was the last thing Mao wanted then.

Nixon and Kissinger began to use what eventually turned out to be false piece of intelligence from the Indian Cabinet. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had supposedly told the Cabinet of her plan to attack West Pakistan and take over Pakistan-administered Kashmir along with East Pakistan. Kissinger feared if these were allowed to happen, the image of the US will fall in the eyes China, the USSR, and the rest of the world. On December 8, Kissinger told Nixon to move the US navy into the Bay of Bengal to warn Moscow.

Kissinger told the Soviets that the US had a military pact with Pakistan (actually the vaguely worded 1955 Baghdad Pact, which had not been ratified by Congress) and said that US would move troops to aid Pakistan. This set the cat among the Soviet pigeons, as Raghavan puts it. Indira Gandhi immediately sent her envoy D. P. Dharto assure the Soviets that India had no designs on West Pakistan or Pakistan-held Kashmir.

However, after the Soviets confirmed that the USS Enterprise was moving towards the Bay of Bengal albeit in the guise of evacuating American citizens from East Pakistan, they wanted India to speed up the military campaign and achieve the objectives quickly. Britain and France also asked India to “finish the job quickly”.

This necessitated a complete revision of the original plan to avoid attacking Dhaka, the ‘geopolitical heart’ of East Pakistan. According to Raghavan, some junior officers had already abandoned the original plan and were heading for Dhaka.

Seeing his defences cracking, Maj Gen. Rao Farman Ali Khan, Military Advisor to the East Pakistan Governor A. M. Malik, sent a proposal for a peaceful formation of a government in Dhaka and the safe repatriation of all Pakistani troops to West Pakistan. But he did not mention surrender. Pakistan’s military ruler Gen. Yahya Khan rejected Farman Ali’s proposal saying it was conceding an independent Bangladesh.

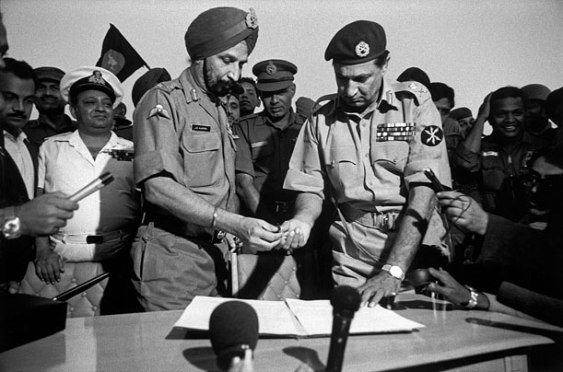

However, when Indian General Manekshaw asked the commander of the Pakistani troops, Gen. A. A. K. Niazi, to surrender, he readily agreed. President Yahya Khan also fell in line. On December 16, 93,000 Pakistani troops laid down their arms peacefully and following the Simla Agreement in August 1972, all POWs were repatriated to Pakistan.

– -P K. Balachandran is a senior Colombo-based journalist who in the past two decades, has reported for The Hindustan Times, The New Indian Express and the Economist