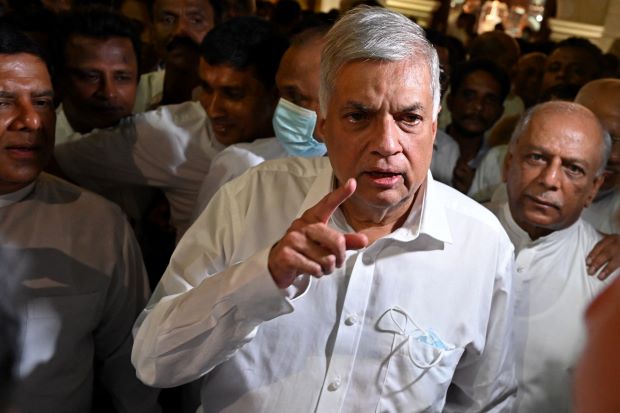

Ranil ‘swings’ into action, shows who is the boss

By N. Sathiya Moorthy

In what friends and admirers, especially in Colombo’s overseas diplomatic corps, had not expected of him, Sri Lanka’s new President Ranil Wickremesinghe ‘swung’ into action, on his day one in office, to restore law and order in the country that had been badly affected since the ‘Aragalaya’ protests began against the then reigning Rajapaksa clan, weeks ago. If the forced, and at times violent, removal of the protestors from the main venue that included the President’s Secretariat, was only a beginning in this regard, Wickremesinghe also did not mince words with Western diplomats who condemned the joint police-military action at midnight, in double-quick time as in the past weeks and in no uncertain terms.

In what was said to be in lighter vein, President Wickremesinghe asked Western diplomats, who he invited for an evening meeting, what would their governments have done if ‘peaceful protesters’ had similarly occupied the office and residence of their president, back home. If nothing else, this was not the Wickemesinghe they had known in the past, and had not expected as president, either. In particular, he pointed out how the US deployed troops to vacate violent Trump supporters after they had stormed into the Capitol, leading to firing-after their candidates had lost the presidential election last year.

Wickremesinghe also pointed out how not one of those diplomats had tweeted their concern when his personal residence was set ablaze (and so were those of 78 ruling Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) politicians, including that of outgoing Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa, on the evening of May 9, all across the Sinhala South), but jumped the gun without proper enquiry to condemn the security forces for clearing official buildings of protesters, who had defied court orders — and had also declared that they would do so. In future, he told them, they were free to contact officials for clarification without getting carried away by social media posts.

The reaction, if any, of the diplomats who met him is not known — but Wickremesinghe’s message was clear. Yes, Sri Lanka as a nation and he, as its new president, would not compromise on specifics even when it meant that they were still dependent on the West and their institutions for critical aid and assistance to face-off the continuing economic crisis, which will haunt the nation for nearly the next decade. The message should go also to the ‘Core Group’ of the US and its allies that are pursuing Sri Lanka’s ‘war crimes’ and fresh allegations of continuing human rights violations almost on a daily basis, at the United Nations Human Rights Commission (UNHRC) — and also issued a statement on the current action of the security forces, which came past midnight.

Rare gesture

In the same vein, the new president re-appointed ‘Gota man’ and former army veteran, Gen Kamal Gunaratne (retd) as defence secretary, indicating continuity without change in matters of national security. Gunaratne is a decorated field commander from the conclusive Eelam War IV against the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in 2009, and has been charged with ‘war crimes’ along with others of his ilk.

In a rare gesture, Wickremesinghe began his official presidential duties by spending time with the security forces who were guarding Parliament, which too the protesters had tried to storm, as if to nullify all symbols of the nation’s democracy. A day later, he visited the defence headquarters, as if to indicate that as their supreme commander now, he would protect their interests, in every which way. Though he might not have said so, it should include the UNHRC-initiated moves from the past and in the future.

Uncharitably, the social media however sought to ridicule Wickremesinghe’s statements and gestures as his way of distancing himself from the West, whose foil some claim to be, is to ‘finish off’ the Rajapaksas politically. They point to the way Mahinda Rajapaksa wantonly distanced himself and his party from Ranil’s victory in the parliamentary vote, by declaring that they had fielded and supported only his rival, Dulles Alahapperuma — but lost.

To them, the bluff was called when Ranil inducted all of Gota’s ministers, and for prime minister chose an old friend in veteran politician Dinesh Gunawardena, 73, who has been close to the Rajapaksas for years and decades. Leader of the Mahajana Eksath Peramuna (MEP), one of the peripheral left parties that the Rajapaksas had promoted alongside their reformed-socialist Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP)/SLPP, Gunawardena is among the few that Gotabaya in particular had entrusted with key portfolios, only for them to become early rebels, long before the public took to the streets.

Dinesh was Gota’s first foreign minister before he swapped places with veteran G. L. Peiris, then education minister. In a way, Gunawardena, who did his higher studies in business management in the Netherlands and the US, became the sole candidate for the prime minister’s job after Peiris, even while being the chairman of the Rajapaksa-centric SLPP, backed rival Dulles Alahapperuma for the presidency and seconded his name in Parliament.

Wickremesinghe has since reiterated his earlier call for all parties to join the government, indicating that he would induct more ministers to make it more representative. As if to message that he meant business, he has fast-tracked an independent probe against political veteran Nimal Siripala de Silva, an SLFP rebel who had re-joined the Gotabaya government with Ranil as prime minister and had to be dropped when the leader of the Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB) and the opposition levelled corruption charges against him in Parliament.

Unenviable task, but…

As president, Ranil’s task may be the most unenviable of the kind in the world today. But this was also the one he had coveted all along. In a way, he is the right man at the right place at the wrong time. He has only a year to prove himself in the new job, with the Rajapaksas as the parliamentary, and hence ministerial crutch with none of them owning up direct responsibility — before he could aspire to become president in his own right.

As with his six terms as prime minister, Wickremesinghe will not have a full five-year term as president now. Nor is he directly elected by the people, as ordained. Instead, he has been chosen by Parliament, to complete the unfinished one-year-plus of Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who fled and quit, under pressure from the people who had voted him to power only three years earlier.

Presidential elections are due in the third quarter of next year. In between, President Wickremesinghe is also expected to dissolve Parliament when the constitutionally-mandated minimum life of the present House expires in February next. Both are among the widely-discussed political solutions and broadly accepted by all electoral stake-holders even as the anti-Rajapaksa protests were raging across the country.

In between, Wickremesinghe will also have to move a constitutional amendment to restore the supremacy of Parliament, acting through the Cabinet with the prime minister as focus under the 19th Amendment of the Constitution, which the successor Gotabaya regime had reverted to the earlier existing all-powerful executive presidency. In doing so, his leadership, with the equally-experienced but even more discredited Mahinda Rajapaksa watching over his shoulders, would have to handle multiple demands for expanding the scope of what will then be proposed as the 21st Amendment, most especially on minority Tamil demands that are of interest to the very generous Indian neighbour.

Air of permissiveness

But this is only a part of the President’s task — and possibly among the easier ones. The government has to restore a semblance of order in everyday life, both of the rulers and the ruled, which was originally lost with the COVID lockdowns two year ago, but went haywire when the anti-Rajapaksa protests commenced earlier this year.

The overnight poverty in many homes caused by the unprecedented economic crisis and the air of permissiveness accompanying the Aragalaya protests, big and small, both in urban and rural areas, had reportedly led to a complete breakdown of law and order, as witnessed in the organized arsonist attacks on the homes of 78 ruling SLPP leaders, starting with all Rajapaksas in public life, as early as May 9, spread across the Sinhala South. Protestors also killed a ruling party parliamentarian and his police security that day, and could pass them off as suicides until their post mortem reports showed otherwise.

The police have made hundreds of arrests on the May 9 incidents, and claim to have made some progress in the investigation into the arsonist attack on the private residence of Prime Minister Wickremesinghe, now President, on the evening of July 9. That was on the day protestors broke security cordons and took over the President’s Secretariat and official residence, forcing incumbent Gotabaya to first go undercover, and then flee — before quitting. Wickremesinghe and his wife Maithiri lived to become President and First Lady, only because of a police tip-off for them to escape before arsonists reached their home.

Restoring economy

For the new president, restoring the economy is the key to the nation’s very survival and his own success. He will have to negotiate hard with multiple international players, starting with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) from where he had left as prime minister and finance minister under predecessor Gotabaya. For the IMF ‘bail-out’ package to work, the leadership has to negotiate the rescheduling of the $51 billion overseas debt, which the Gotabaya dispensation decided to ‘default’ for now.

As President Ranil’s foreign minister, Gotabaya’s one-time personal lawyer Ali Sabry too has reiterated that negotiating with the IMF and international creditors is top priority. He replaces long-term Foreign Minister G. L. Peiris. A one-time justice minister under Gotabaya, Sabry negotiated with the IMF after taking charge of finance for a short while, when Basil Rajapaksa too had to quit under public pressure.

And on these two sets of negotiations would depend the short, medium and long-term assistance that the nation expects to obtain from friendly and not-so-friendly nations. On day one as Gotabaya’s Prime Minister, after Mahinda had quit under public and political pressure, Wickremesinghe proposed an aid consortium of donor-nations, as used to be the case in the previous century. As if to modify it, so to say, he soon spoke about a consortium comprising three Asian powers, namely, India, China and Japan.

Multiple messaging

In a significant message to India, the nation’s Tamils and the international community, President Wickremesinghe has ranked Fisheries Minister Douglas Devananda, from the northern Jaffna district, as the second-ranking minister after the prime minister, in the warrant of precedence. This is the first time that Devananda, a near-permanent, long-term member of most Cabinets since the mid-nineties, is a part of a Ranil-led team.

If inducting Devananda into the team was intended to reassure India and the international community – the latter ready to fry Sri Lanka one more time at the UNHRC, in its upcoming session in September — there were separate signals to the island’s ethnic Tamil population and polity. That the ethnic issue is a top priority for the new government, too, but the 10-MP Tamil National Alliance (TNA) could not act as if they are the ‘sole representative’ as the LTTE before it, also because some top leaders had wanted him out along with Gotabaya.

Prime Minister Gunawardena, talking to newsmen, said that the ethnic issue was a top priority for the new government and the TNA especially should trust the new president. Incidentally, at least five of the 10 TNA parliamentarians are believed to have voted for Wickremesinghe though the ‘unanimous decision’ was to back rival Dulles.

As prime minister under Gotabaya, Wickremesinghe had repeatedly asserted that India was the only nation to help Sri Lanka in its hour of economic crisis — through food, fuel and medicine supplies, and rescheduling multiple credits that were due for repayment. All this are bound to keep India in good stead also with a majority of Sri Lankan masses, both urban and rural, intellectuals and otherwise, when it comes to facilitating big-ticket Indian investment projects, both existing and new ones, there is still a section of other Left and Right parties that are not part of the government that continue to remain anti-India.

Awaiting stability?

Incidentally, China that had remained distanced from Sri Lanka’s economic crises through the peak period — there will be multiple peaks in the coming months and years — has since opened up. According to the Chinese state media, President Xi Jinping has offered his support to Sri Lanka’s new president. In his message, Xi expressed the belief that Sri Lanka will be able to move towards economic and social recovery and he is “ready to provide support and assistance to the best of my ability to President Wickremesinghe and the people of Sri Lanka in their efforts”.

Does this mean that China, uncomfortable about dealing with political transitions, especially of the democratic kind, was waiting for a new and stable government in Colombo, before opening up — and possibly opening up its purse-strings? If so, will it be in competition to the IMF and the West, if not to India, or in cooperation and coordination with them all?

-N. Sathiya Moorthy is a Chennai-based policy analyst and commentator and this article was originally featured on firstpost.com