Putin’s ‘macho doctrine’: Implications for Ukraine

By Marwan Bishara

Vladimir Putin will have you know that he did not want this war; that it was imposed on him. He did the impossible to avoid invading his beloved Ukraine, but there are things that even a superpower, a super-duper patient leader cannot endure.

The Russian president has long warned that Ukraine belongs to Russia; if it could not have her, then nobody else could.

Alas, no one listened.

Neither he nor Russia had received the respect they deserved, and that was just unacceptable and utterly infuriating to this macho modern-day tsar.

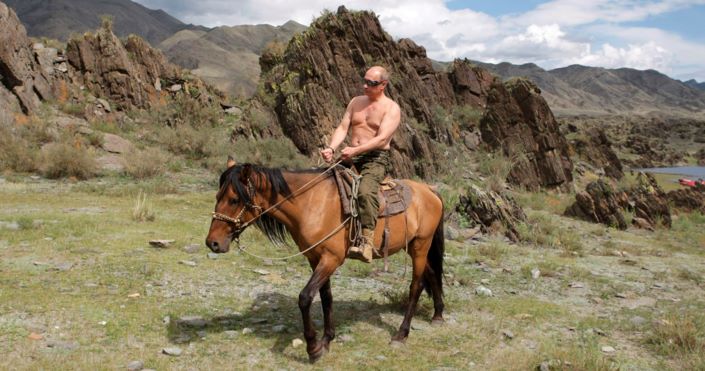

By macho, I am not alluding to Putin’s ice swimming, judo fighting, and bare-chested horseback riding. But to his visceral assertiveness, willingness, and determination to use Russia’s military power to advance Russian interest.

Putin has made his views abundantly clear over the years, warning the West to end its geopolitical adventurism and keep away from Russia’s sphere of influence; to stop fishing and flirting with Ukraine, to no avail.

Uncharacteristically for a former KGB operative, Putin’s ominous speech on the eve of the Ukraine invasion was especially emotional, bitter and angry. The West was forcing his hand and he had no choice but to act before it was too late.

Putin could have endured the disappointment and the jealousy, but not the betrayal; Russia just could not live with Kyiv’s shameful infidelity. Not after a 300-year partnership, not after all that Moscow had done for Ukraine, endowing it with territory, money and prestige.

Worse, traitorous Ukraine had turned into a Western “springboard against Russia”. For Putin, Ukraine’s duplicity, the affection between Russia’s soulmate and its sworn arch-rival, was not just vulgar, it was dangerous for Russian national security.

Despite having made his peace with Ukraine’s desire for separation and grudgingly accepted joint custody of the twins, Luhansk and Donetsk, in 2014, he believed Kyiv continued to abuse the eastern provinces for the following eight years, providing him the pretext to intervene.

The latest Russian doctrine he godfathered is committed to protecting all Russians, including the 25 million that were left outside Russia’s borders following the collapse of the Soviet Union, and especially the 12 million Russians in Ukraine.

To that end, and to leave no room for doubt, Putin ordered 720,000 fast-track passports to be issued for Russian separatists in eastern Ukraine, giving himself the moral and national justification to intervene, as he did in Crimea in 2014.

And so he did. Again.

But, none of this should have come as a surprise.

After the Cold War ended and before Putin came to power, Russia foresaw two types of geopolitical challenges: strategic threats, notably from the West, and imminent dangers from inter and intra-state conflict among the recently seceded states that made up the Soviet Union.

For much of the 1990s, Moscow engaged Washington to manage emerging challenges, coordinated democratic reforms, and even considered joining the European Union and NATO. But neither seemed welcoming or even remotely interested. If anything, NATO wanted Russia weak and contained, and went on to expand its membership eastwards at its expense.

That was not the first time that NATO snubbed Moscow. According to Putin, NATO rejected Russia’s offer to join the organization after the second world war, forcing the USSR to form its own ‘Warsaw Pact’.

Interestingly, Putin has admitted that the Pact’s assault on Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968, were big mistakes that produced the Russophobia that we witness in Eastern Europe nowadays.

So when Putin famously fretted over the collapse of the Soviet Union as “a great catastrophe of the 20th century”, he was not wishing for its revival. Rather, like countless Russians, he was lamenting Russian disbursement and decline. Even the West’s favourite Russian dissident, Alexey Navalny supported Moscow’s annexation of Crimea.

From there on, Putin promised to fully restore Russia’s historical glory in the former republics of the USSR, and has in fact made major inroads in most, including most recently in Kazakhstan.

But without Ukraine, the “birthplace of the Russian nation”, Russia’s honour could never be restored. With Ukraine, Putin could make Russia great again. In short, it all hung on Ukraine.

He presumably tried the gentle diplomatic approach and even promised to “respect” Ukraine’s wishes, but coercion and the threat of force were always lurking in the background.

And when Ukraine refused to join Russia’s sphere of influence, like say Belarus, Putin insisted rather emphatically that it must become a neutral buffer state, even a demilitarized state.

As in all divorces, this disagreement on the conditions of official separation had to have negative repercussions at home and beyond, and in a macho man’s case, it had to turn ugly.

As Ukraine reasserted its sovereign right to invite whomever it wished to Russia’s own doorstep, Putin reacted with vengeance, denying it sovereignty altogether.

The Russian leader used every trick in the Washington handbook to justify the invasion, accusing Kyiv of committing genocide and of looking to develop nuclear weapons. But propaganda aside, he simply wanted to keep Russia in and the United States out of Ukraine.

Putin believes Russia was born to be a great power; considering it was an empire before even becoming a nation. But today, such greatness is possible only after recovering Little Russia (modern-day Ukraine) and ‘White Russia’ (Belarus). He also believes that historically, powerful nations like Russia, China and the US have the right, if not the duty, to rule over their regions and, together, rule over the world.

To that end, the ‘Putin doctrine’ is committed to expanding Russian military power and deploying it in defence of its interests and those of its allies, in order to compel the West, once again, to recognize Moscow’s superpower status, both in words and deeds.

But then again, the Russian Federation is no Soviet Union; it lacks the military prowess, ideological mission and the geopolitical clout of its predecessor. The Russian economy is smaller than even a medium Western economy like Italy.

And, lest Putin forgot, the mighty Soviet empire lost to the West not for its lack of nuclear weapons and spooks, but rather for its bleak row model and a weak economy, which made it impossible to compete or stay in the game.

That is why Putin’s Ukraine adventure could prove devastating to Russia, considering the massive sanctions and the costly occupation. Unlike his previous little wars in Chechnya, Georgia and Syria, this may well prove reckless.

Indeed, the Russian leader may have underestimated the West’s “smart power” and its capacity to cause terrible pain through financial, diplomatic and other means. The West’s deployment of its formidable corporate arsenal against all spheres of Russian life is truly mind-blowing, whether in banking, technology, manufacturing, communication, transport or even entertainment.

Putin may have also underestimated Ukrainians’ passion for independence and willingness to resist Russian hegemony. Since the beginning of the invasion, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has mastered the act of “David vs Goliath”, skilfully projecting an image of both vulnerability and heroism.

If Washington and Kyiv succeed in turning Ukraine into Russia’s second Afghanistan, Putin’s doctrine could go from macho to sadistic before it turns into an utter disaster for everyone concerned.

It is never too late to stop fighting and start talking more seriously and sincerely about future relations. Now that Putin has finally gotten the world’s attention, he needs to stop making threats and start making sense.

-Marwan Bishara is senior political analyst at Al Jazeera, where this article was originally featured. He writes extensively on global politics and is widely regarded as a leading authority on US foreign policy, the Middle East and international strategic affairs