By Ezra Fieser

HONG KONG -Nishan de Mel is a bit obsessed with debt crises. Primarily because de Mel, an Oxford-trained economist, has long suspected that the underlying cause is often bad governance. So when his native Sri Lanka fell into an economic disaster of its own a couple of years ago, he decided to pore through decades of data to put his theory to the test.

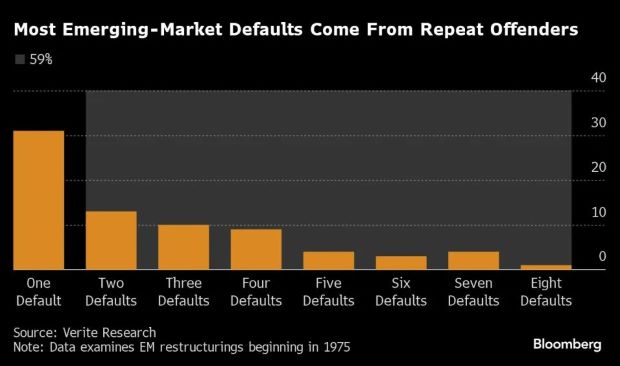

“It was clear, there was a correlation between poor governance and the likelihood of a repeated government default,” he said.

After Sri Lanka fell into default, de Mel, armed with this evidence, urged the international financial community to consider an unconventional proposal. What if, he asked, bond investors handed incentives to the government — like, say, a reduction in interest rates — for things like improving tax collection?

It’d be good for the country and, by reducing default risk, good for creditors, too. He figured the idea would go nowhere. “I gave it a one-in-1,000 chance,” says de Mel, who runs Verite Research, a think tank based in the Sri Lanka capital of Colombo.

Fast forward a year and the clause is now a key element of the $12 billion restructuring deal that Sri Lanka is negotiating with creditors. It will be on the table when they two sides resume talks as part of the country’s larger rework of its debt.

Many of the biggest creditors already backed it: A group including BlackRock, Eaton Vance Management, T. Rowe Price Associates and Morgan Stanley’s asset management unit has publicly expressed support.

Representatives for the committee declined to comment as the measure is being negotiated. In documents released after the first round of talks with the government ended, the bondholders called the proposal “an efficient incentive for the authorities to improve governance and reduce corruption vulnerability, benefiting both the country and bondholders”

Under the so-called governance-linked bond, the interest rate Sri Lanka pays would be cut by as much as .50 percentage points if the government can meet certain targets.

Shanta Devarajan, a professor at Georgetown University and former acting chief economist for the World Bank, sees it as a potential blueprint that can help cut down on repeated defaults.

“This is attacking the problem at its root,” he said. “Around the world, many of us felt the problem in Sri Lanka has been governance.”

The security structure borrows from another type of ESG debt, known as a sustainability-linked bond. In that case, the goals are environmental, such as reducing emissions of carbon dioxide.

It also adds to a growing number of debt instruments across emerging markets that link bond payments to measures taken by the government. El Salvador recently added a warrant to its debt sale that gives investors a higher interest payment if the nation doesn’t win an IMF package or credit upgrade. In Suriname, creditors introduced a value-recovery instrument that would give them a share of future wealth from an offshore oil field.

In the Sri Lanka deal, the two sides are also negotiating a security that links repayments to the country’s economic performance. The governance bond, however, is a first.

To qualify for the step down in the coupon, the government would have to fulfil two metrics, like upping the amount of taxes it collects as a percentage of gross domestic product and publicizing information on who receives tax exemptions. An independent third party would verify the progress and if the government fails, the coupon will remain the same.

For some, that raises questions about how it can be measured.

“Investors are going to want more specific and detailed metrics,” said Oren Barack, managing director of fixed income at New York-based Alliance Global Partners. “It could have some significant upside but you’d hope and expect there would be more clarity and specific metrics outlined.”

For Wall Street, it presents something of a role reversal. Bond investors have long been vilified for turning a blind eye to corruption in foreign nations or ploughing money into a country regardless of its adherence to democracy.

But for de Mel, it makes perfect sense. “If you incentivize the government to behave better, you reduce the risk of a future default,” he said.

He traces Sri Lanka’s 2022 default directly to poor governance. That year, tax collection fell to less than 8% of gross domestic product, one of the lowest levels in the world, after a series of changes to tax law. That helped spark a financial crisis, de Mel said.

The island nation of some 22 million people ranks 115 out of 180 nations on the Transparency International corruption perceptions index.

“You can’t solve an economic crisis without solving the question of governance,” de Mel said.

-Bloomberg

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.