Continuing tragedy of war widows in Sri Lanka

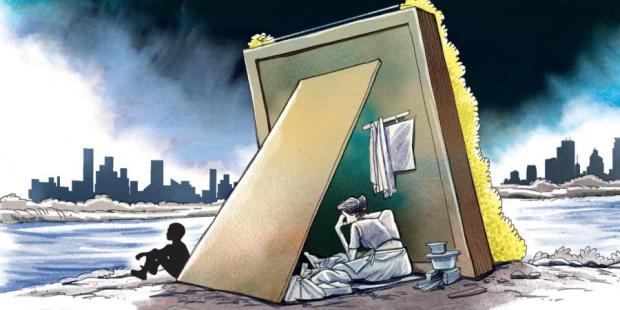

The Fourth Eelam War ended back in 2009. But for the women left behind, the battle for survival still continues

By V. Suryanarayan

Thomas Hawkins, in his poem, The Tragedy of War, has written: “The tragedy of war, ends not with those who died, for the tragedy continues in fragile minds, who did survive”. The poem epitomizes the sad plight of 70,000 war widows, mainly concentrated in the Northern and Eastern parts of Sri Lanka.

The Fourth Eelam War ended in 2009. But for the women left behind, the battle for survival continues. In the Tamil areas, the death squads of the government took away many young men, who ‘disappeared’ leaving behind their wives and children as orphans.

According to Thomson Reuters Foundation, Nathkulasimham Nesemalhar, 54, took a flight from Colombo to Muscat in March 2017.

She was happy she had a boarding pass as she hoped that by working as a housemaid, with a monthly salary of Rs 30,000, she would be able to repay debts and her three children could lead a normal life. But her hopes turned into a nightmare. When she arrived in Oman, she found she was enslaved with other women in a dimly lit room, with no ventilation. She was taken every day to different houses, to work from morning to night, and brought back and locked again. Nesemalhar said, “There were 15 of us. We never got paid”. Finally, they were brought back to Sri Lanka when the government intervened.

Nesemalhar’s case is not unique. The lack of opportunities for self-employment is making Tamil widows victims of human traffickers who sell them as slaves in West Asian countries. Reports of physical and mental abuse are common. Women are reluctant to speak about sexual abuse and rape, fearing shame and stigma. Since it is easy for Muslims to get jobs in West Asia, Hindu women marry Muslims, become the second or third wife of someone, get a passport and proceed to West Asian countries to lead a life of misery and toil.

It is not only the Tamil women who were rendered widows. Hundreds of Sinhalese soldiers died during the ethnic conflict and their wives became widows. They are eligible for pension benefits equivalent to their husband’s last salary. There is no equivalent treatment of Tamil widows.

According to UNDP estimates, Sri Lanka still ranks high in terms of human development index, better than other South Asian countries. Because of the war, the Northern Province remains one of the least developed parts. More than a fifth of the 250,000 households in the Northern Province are headed by widows, who have become breadwinners.

The maternal mortality rate is 30% against 22% for the whole country. M. L. A. M. Hizbullah, the then Deputy Minister for Women‘s Affairs and Child Development, admitted in September 2010 that the government had a list of 89,000 war widows—49,000 in the Eastern Province and 40,000 in the Northern Province. Among them were 12,000 below the age of 40 and 8,000 who had three children.

The government has done very little to improve the situation. Widows have to produce the death certificate of their husbands to receive Rs 50,000 as compensation. The widows, in most cases, cannot produce death certificates, especially those of the ‘disappeared’. The rest are given Rs 150 per month, not even sufficient to meet a day’s expenditure.

I was able to persuade Somi Hazari (who unfortunately died last month), a businessman involved in export-import trade with Sri Lanka, to chalk out a plan of action for starting poultry farms in the Eastern Province. The mother hens would be exported from India, assistance would be provided for starting the poultry farms, and eggs and chickens would be bought every day and sold throughout the country. If implemented it would have provided a decent income to many households.

The only hitch, according to Somi, is the government rule that mother hens cannot be imported from India. The Sri Lankan diplomats based in Chennai and New Delhi assured us that the ban would be lifted. The ban has not gone even today and Somi’s plan of action fizzled out.

Prabhakaran’s war strategy, in many ways, contributed to the present situation. During the fairly long spell of the ceasefire, 2002-06, he allowed the guerrillas to go home and get married. Once they started family life and had children, their revolutionary zeal began to wane.

Milinda Moragoda, the astute Sinhalese politician who was involved in negotiations with Anton Balasingham during the ceasefire period, told me that a prolonged ceasefire would bring out into the open all the contradictions within the LTTE. The Eastern guerrillas raised the banner of revolt because they felt that the Northern leaders were using them as cannon fodder.

Later they made common cause with the Sri Lankan government. Prabhakaran’s supply lines were destroyed, thanks to the inputs made by the Indian intelligence agencies. The crimes committed by the Tigers—the assassination of moderate Tamil leaders and using women and children as shields against army reprisals—disproved its claim that it was a national liberation organization. The LTTE was forced to retreat from place to place and finally got decimated in May 2009.

The sad aspect of the present situation is the fact that India, especially Tamil Nadu, is not doing anything substantial to wipe the tears of the Tamil war widows. I have been pleading with the Tamil Nadu unit of the BJP that it should send a team to Sri Lanka’s North and the east, study the problems in depth, and chalk out and implement self-employment measures for these unfortunate women.

Whenever I spoke to them, the leaders would nod their heads in approval, but no follow-up measures were taken. Like other Dravidian parties, they also make fiery speeches “full of sound and fury, signifying nothing”.

“What we call the beginning,” T. S. Eliot wrote, “is always the end”. Let me, therefore, conclude from the poem that I quoted in the beginning. “So I say to leaders of this world, this nightmare should be gone, please realize once and for all, that a war is never won”.

-V. Suryanarayan is a founding director and a senior professor (retd), Centre for South and Southeast Asian Studies, University of Madras. He can be contacted on suryageeth@gmail.com. This article was originally featured on newindianexpress.com