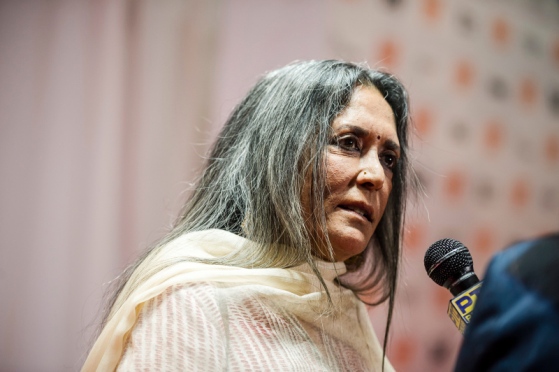

‘Funny Boy’ filmmaker Deepa Mehta wants you to smell Sri Lanka

The Oscar-nominated director best known for her Element Trilogy has made a queer coming-of-age tale that's equally poignant and joyous

By Jude Dry

From her groundbreaking Elements Trilogy to ‘Funny Boy’, her gorgeous new queer coming-of-age tale currently screening on Netflix, Deepa Mehta makes films to delight all of the senses. For her immersive adaptation of Sri Lankan-Canadian author Shyam Selvadurai’s beloved novel ‘Funny Boy’, Mehta kept one particular sense in mind: “I want people to smell ‘Funny Boy.’ You should smell it, smell the palm trees, you can smell the water.”

Raised in New Delhi and living in Toronto since 1973, the lauded Indo-Canadian filmmaker’s body of work spans globally in location and subject matter. Mehta is best known for her Elements Trilogy (the origin of that name are a mystery to her), which includes the controversial lesbian romance ‘Fire’ (1996), the Partition era family drama ‘Earth’ (1999), and the Oscar-nominated ‘Water’ (2005). India submitted the film for the 2007 foreign-language Oscar, and this year submitted ‘Funny Boy’, but the Academy deemed it ineligible because it used too much English, accepting backup entry, ‘14 Days, 12 Nights’, instead. Mehta’s film is, however, still eligible to compete in other categories, including Best Picture.

Mehta’s socially-conscious themes have ignited controversy and violent protest in India, as well as government censorship. The love scenes between two women in ‘Fire’ led to the destruction of movie theatres; and ‘Water’ took years to complete after Hindu mobs destroyed the film’s Ganges River sets, forcing Mehta to shoot in Sri Lanka instead.

‘Funny Boy’, which follows a wealthy Tamil boy’s coming of age amidst escalating Sinhala-Tamil tensions, is no less provocative than Mehta’s previous work. The queerness of the story is certainly taboo in Sri Lanka, where it is still illegal to be openly LGBTQ. But it was the film’s portrayal of the 1983 riots, a vicious anti-Tamil pogrom known as Black July, that had to be treated with the utmost delicacy.

“Sri Lanka is not very different from the rest of the world,” Mehta said during a recent video interview. “We’re all struggling with identity and we’re all struggling with trying to heal because there’s so much hatred and divisiveness around.”

‘Funny Boy’ is the first major film to dramatize the events of 1983, a subject which outsiders know little about, and that is often swept under the rug in Sri Lanka. Mehta was struck by feedback from Diaspora Sri Lankans after a small early screening of the film.

“For many people, the memory, because they’d been through what they had, with the terrible pogrom that happened in Sri Lanka, which many people don’t know about, was very difficult,” said Mehta. “They sort of suppressed it, and then suddenly this film came along and it addressed it, because it’s very specific and yet universal in that sense. And it was difficult but at least the healing — forget the healing — let the dialogue begin!”

Despite its heavy subject, for most of its running time ‘Funny Boy’ is a colourful and lively celebration of life in Sri Lanka before the riots. Titular ‘Funny Boy’ Arjie is played by two actors: the impressionable child by Arush Nand and the ebullient young man by Brandon Ingram. They both infuse Arjie with a sense of wonder and play — he is at times defiant of the gender norms constraining him, at times eager to please his traditional Tamil parents — but always a grand diva.

Mehta captures the actors at their most natural; the camera appears to flow as freely as Arjie plays, dances, and leaps headfirst into first love. “I remember talking with [my DP] Doug Koch about cinematography rather philosophically,” Mehta said. “The camera was always dictated by the actors, not the other way around. And it was always handheld. We did have a dolly shot, but it was on a wheelchair, we didn’t have tracks.”

That’s a trick she picked up from the great Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray, to whom ‘Funny Boy’ pays homage. “I remember spending five days with him when he was shooting his last film, as an observer,” said Mehta. “And there he was in a wheelchair, there were no tracks. So, that’s what I wanted from ‘Funny Boy.’ I said, ‘We want the movement to be smooth, but yet not completely smooth — immersive.’ … I wanted to be there with the characters, I wanted the camera to be observing a family, a paradise that falls apart.”

The idea of capturing paradise lost is key to understanding how Mehta can make films that feel so joyous and light, despite their often heavy subject matter. For this reason, Mehta used as little artificial light as possible, instead letting the Sri Lankan lights, colours, sounds, and yes — smells — fill the screen unencumbered by artificial embellishment. She allowed cinematographer Douglas Koch to use only one light — a compromise from her initial outright ban.

“That wonderful feeling that it’s not lit. What’s the colour palette? It’s ochre, it’s green, it’s blue. It was all real, we didn’t light it,” she said. “We didn’t do it in the post, or whatever. We didn’t have money to do anything in the post anyways. But it was also about the red of blood when it comes, so the way he shot it was always thinking of the emotional core of the scene and always about: ‘if this is paradise, wherever paradise is, it can be lost.’”

“Funny Boy” is currently streaming on Netflix.

-This article was originally featured on indiewire.com