When might becomes law: Venezuela, Washington, and the collapse of the global order

The capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro by United States forces in a lightning military operation marks one of the most extraordinary and alarming episodes in modern international relations. A sitting head of state seized by a foreign power, flown out of his country in handcuffs, and presented before a domestic court of another nation is not merely a dramatic news event. It is a watershed moment that threatens to upend long-standing principles of sovereignty, international law, and the fragile architecture of global governance.

President Donald Trump’s declaration that the United States would now “run” Venezuela until a transition of power is arranged moves this episode beyond a covert raid or limited intervention. It signals an assertion of direct external control over a sovereign state, without United Nations authorization, without congressional approval, and without any credible multilateral framework.

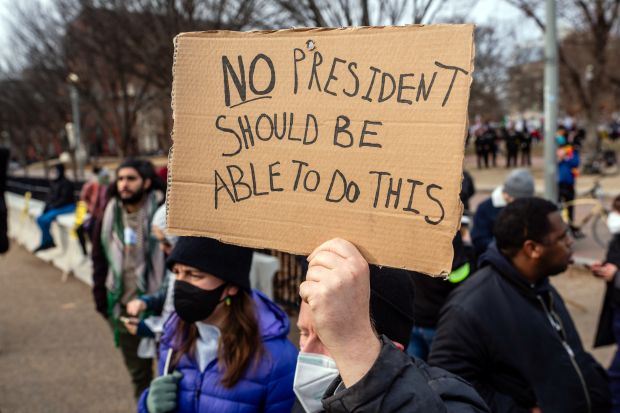

If left unchallenged, this act risks normalizing a dangerous doctrine: that powerful states may unilaterally remove governments they deem undesirable and assume administrative authority over entire nations.

The Trump administration has framed the seizure of Maduro as a law-enforcement action, citing US indictments on drug trafficking and weapons charges. Yet, the use of overwhelming military force, including airstrikes, the dismantling of air defences, electronic warfare, and Special Operations raids, pushes this far beyond any reasonable definition of policing.

Under both US constitutional law and international law, the operation stands on precarious ground. Trump acted without explicit authorization from Congress, despite bipartisan efforts underway to restrict presidential war-making powers in Venezuela. More critically, the action appears to violate the UN Charter, which prohibits the use of force against another state except in cases of self-defence or with Security Council approval, neither of which applies here.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres was unequivocal in his response, warning that the seizure of a country’s leader by another country constituted a “dangerous precedent” and expressing deep concern that international law had not been respected. His words underscore a growing reality: the rules-based international order is being hollowed out, not by its declared enemies, but by those who once claimed to be its guardians.

The operation in Venezuela fits a familiar historical pattern. From Panama in 1990 to Iraq in 2003, the United States has repeatedly justified regime change through a combination of criminal allegations, moral imperatives, and strategic necessity. Each time, the promised outcomes – stability, democracy, prosperity – have proven elusive.

Trump’s assertion that the United States will oversee Venezuela until a “proper transition” is arranged raises immediate questions: Who defines what is proper? For how long? And under what authority? The absence of clear answers suggests not a carefully planned democratic transition, but an improvisational exercise of raw power.

The swearing-in of Vice President Delcy Rodríguez as interim president, conducted in secrecy and rejected by Washington even as Trump claimed she was willing to cooperate, illustrates the political vacuum such interventions create. Far from stabilizing Venezuela, the operation risks plunging the country into deeper uncertainty, fragmentation, and possibly prolonged conflict.

While the administration insists the intervention will “not cost” the United States anything, Trump’s remarks about American oil companies rebuilding Venezuela’s energy infrastructure tell a different story. Venezuela holds the world’s largest proven oil reserves, along with vast mineral wealth critical to global industries. Control over these resources, and over who profits from them, has long been a central factor in US-Venezuela relations.

Reports from Washington make clear that three policy goals have driven Washington’s approach: crippling Maduro, using military force against alleged drug networks, and securing access to Venezuelan oil for US companies. When military action aligns so neatly with economic interests, claims of altruism ring hollow.

This convergence of force and profit revives uncomfortable echoes of earlier eras, when intervention was openly justified as a means of securing strategic resources. In the 21st century, such motives are cloaked in the language of law enforcement and democracy promotion, but the underlying dynamics remain strikingly similar.

International reactions to the operation have exposed deep geopolitical fault lines. US allies such as Ecuador and Argentina applauded the raid, while China, Russia, and Iran condemned it as a violation of sovereignty. These divisions mirror a broader global trend: the world is increasingly split between blocs that interpret international law not as a universal standard, but as a tool of convenience.

The United Nations Security Council’s decision to convene an emergency meeting underscores the gravity of the situation. Yet history suggests that meaningful action is unlikely. Veto powers, competing interests, and institutional paralysis have rendered the Council largely incapable of restraining unilateral force by powerful states. The UN’s inability to prevent or respond decisively to such actions raises troubling questions about its relevance in an era of renewed great-power assertiveness.

Perhaps the most troubling implication of the Venezuela operation is what it suggests about the evolving meaning of democracy. When an external power claims the right to depose a government, even an unpopular or authoritarian one, and install or manage a political transition, democracy is reduced to an outcome rather than a process.

This logic is corrosive. It implies that elections, sovereignty, and self-determination matter only when they produce acceptable results. Such a standard does not strengthen democracy; it undermines it, both abroad and at home. It also provides a convenient justification for other powers to intervene in neighbouring states under similarly self-serving pretexts.

The capture of Nicolás Maduro may be celebrated in parts of the Venezuelan diaspora and applauded by Trump’s political allies. But beyond the immediate reactions lies a far more consequential reality. If the seizure of a head of state by another country becomes an acceptable instrument of policy, the world enters a far more dangerous phase of international relations.

Rules, once broken, are hard to restore. Precedents, once set, are difficult to contain.

Venezuela’s future should ultimately be determined by Venezuelans, through political processes that reflect their will and address their suffering. External pressure, diplomacy, and even sanctions may be debated within that context. Military abduction and unilateral control cannot.

What unfolded in Venezuela is not merely a national crisis. It is a global warning, one that challenges the international community to decide whether law will continue to restrain power, or whether power will finally eclipse law altogether.

-ENCL

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.