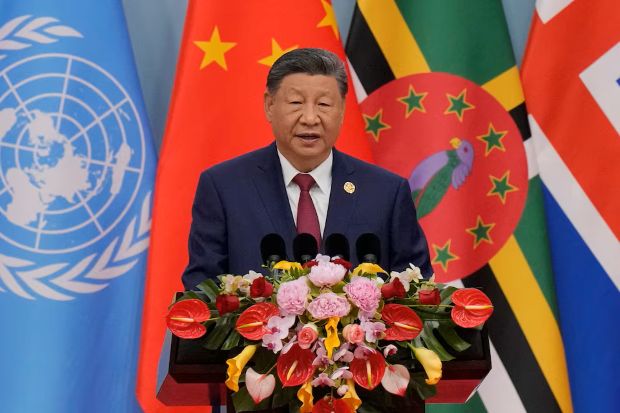

In China, a forbidden question looms: Who leads after Xi?

By Chris Buckley

Behind closed doors in Beijing this week, China’s top officials are meeting to refine a plan to secure its strength in a turbulent world. But two great questions hang over the nation’s future, even if no one at the meeting dares raise it: How long will Xi Jinping rule, and who will replace him when he is gone?

Xi has led China for 13 years, amassing dominance to a degree unseen since Mao Zedong. He has shown no sign of wanting to step down. Yet his longevity at the top could, if mismanaged, sow the seeds of political turbulence: He has neither an heir apparent nor a clear timetable for designating one.

With each year that he stays in office, uncertainty deepens about who would step in if, say, his health failed, and whether the new leader would stick to or soften Xi’s hard-line course.

Xi faces a dilemma familiar to long-serving autocrats. Naming a successor risks creating a rival centre of power and weakening his grip, but failing to settle on a leader-in-waiting could jeopardize his legacy and sow rifts in China’s political elite. And at 72, Xi will likely have to search for a potential heir among much younger officials, who must still prove themselves and win his trust.

If Xi eventually chooses a successor, loyalty to him and his agenda will almost surely be a paramount requirement. He has said that the Soviet Union made a fatal mistake by picking reformer Mikhail Gorbachev, who oversaw its dissolution. On Friday (17), Xi made his intolerance for any disloyalty clear when the military announced that it had expelled nine senior officers, who face prosecution on charges of corruption and abuse of power.

“Xi almost surely realizes the importance of succession, but he also realizes that it’s incredibly difficult to signal a successor without undermining his own power,” said Neil Thomas, a fellow at the Asia Society Policy Institute’s Centre for China Analysis. “The immediate political and economic crises that he faces could end up continually outweighing the priority of getting around to executing a succession plan.”

Speculation about Xi’s future is highly sensitive and censored in China, and only a handful of officials may be privy to his thinking about the issue. Foreign diplomats, experts and investors will be looking for clues from the four-day meeting of the Communist Party’s Central Committee that started Monday (20), bringing together hundreds of senior officials.

The meeting, usually held behind closed doors in the specially built Jingxi Hotel in Beijing, is expected to approve a plan for China’s development over the next five years. Xi has made securing a global lead in technological innovation and advanced manufacturing a priority, and that goal is likely to feature heavily. He and his officials have expressed confidence that their approach can prevail over President Donald Trump’s tariffs and export controls.

“At the heart of strategic rivalry among the great powers is a contest for comprehensive strength,” senior Chinese lawmakers said in a report they issued last month on the proposed plan. “Only by vigorously upgrading our own economic power, scientific and technological strength, and overall national power can we win the strategic initiative.”

In theory, the meeting this week could offer a window into China’s next generation of leaders, if Xi chooses to elevate younger officials into more prominent roles. But many analysts expect him to delay any major moves, at least until after his likely fourth five-year term begins in 2027, and perhaps well beyond that.

“Then I think it has to start looming larger, if not in his own mind, then in the people around him,” said Jonathan Czin, a researcher on Chinese politics at the Brookings Institution who has written about Xi’s succession scenarios and the Central Committee meeting. “Even if the people in his immediate orbit don’t start jockeying for position for themselves, they’re going to be jockeying on behalf of their own proteges.”

Xi has seen firsthand how succession struggles can shake the Communist Party. His father, a senior official, was ousted by Mao. As a local official during the 1989 pro-democracy protests, Xi witnessed how divisions at the top helped tip China into upheaval; ultimately, Deng Xiaoping purged the party’s general secretary, Zhao Ziyang, and installed a new heir apparent, Jiang Zemin.

“Especially as someone who spends so much time studying the lessons of China’s dynastic cycles and the history of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Xi knows that the succession is a major issue he must think through,” said Christopher K. Johnson, the president of China Strategies Group, a consulting firm, who previously worked as a US intelligence official focused on China.

For now, Xi seems convinced that China’s ascendancy depends on his continued stewardship. He bulldozed past the example of orderly retirement set by his predecessor, Hu Jintao, and abolished the presidency’s two-term limit in 2018, enabling Xi to stay in office indefinitely as head of the party, the state and the military.

But each year that Xi stays in power, it becomes harder to find an heir who is both young enough to rule for decades and seasoned enough to command authority in his shadow.

Xi has packed the Politburo Standing Committee — the seven-member body at the apex of party power — with longtime allies. They are in their 60s or older, likely too old to be plausible heirs several years from now, experts said. Xi was 54 when he joined the Standing Committee in 2007, a promotion that underlined his status as a favourite to become the next leader.

Even officials poised to be elevated to central leadership at the next Communist Party congress, in 2027, are probably too advanced in age to succeed Xi, said Victor Shih, a professor at the University of California San Diego who studies elite politics in China.

With Xi likely to serve another term or even longer, his successor could prove to be an official born in the 1970s, likely now working in a provincial administration or an agency of the central government. The party has been promoting some younger officials who fit that profile, said Wang Hsin-hsien, a professor at National Chengchi University in Taiwan who studies the Communist Party.

But Xi also appears to be worried about officials who have not been tested by hardship or responsibility. He has warned that seemingly minor shortcomings in officials can become serious threats in moments of crisis — or, as he has put it, “A small crack can become a massive collapse” in a dam wall.

“Xi is highly distrustful of others, especially those officials who have only an indirect relationship with him,” Wang said. “As he grows older and has fewer connections to the generation of his possible successors, this factor will become more important.”

In the years ahead, the upper ranks of the party may grow more fluid as Xi tests and discards potential recruits for leadership, experts said. Behind the scenes, officials within his circle may jockey more intensely for influence and political survival.

“This will make the succession process more fragmented, because he can’t possibly just have one designated successor,” Shih said. “It has to be a collective to choose from, and that probably also means they will have low-grade power struggles with each other.”

-New York Times

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.