Jane Austen loved music, what was on her playlist?

By Eleanor Stanford

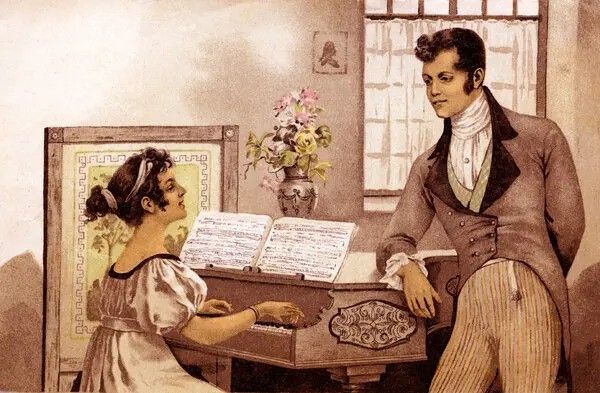

LONDON — When Lisa Timbs sits down wearing a gown at her 19th-century square piano and plays pieces from Jane Austen’s sheet music collection, the feeling, she said recently, can be “spine-tingling.”

Timbs’ audience for such performances tends to be fellow Austen fans, eager to be transported back to the Regency society that Austen brought to life so evocatively in her novels. Hearing Austen’s favourite music on an instrument similar to one that the author herself would have played is a kind of time travel, Timbs said. The sound of the square piano — the first midsize and affordable keyboard to be widely available in England — was quite different from modern pianos, Timbs added: It is generally tuned lower, with a silvery, bright sound.

In the crowded field of Austen appreciation and scholarship, the novelist’s love of music and its influence on her writing has long been a bit of a fringe topic. But in the past decade, after academics at the University of Southampton in England digitized the sheet music collection of Austen and her family, more and more people are turning to the music for new perspectives on her life and work.

This year, the 250th anniversary of Austen’s birth, has been the busiest performance year yet for Timbs and her square piano, she said. Timbs — who bought her first handmade, 19th-century piano in 2012 — will play more than a dozen concerts celebrating the writer, including one Thursday (18) as part of the Jane Austen Festival in Bath in southwestern England.

Throughout her life, Austen lived with members of her immediate family: Starting in 1809, she and her mother, sister and a female friend made a happy household in the village of Chawton in southern England. Austen played the piano and sang, but she practiced early in the morning before the rest of the household was awake, said Gillian Dooley, an academic who wrote a book about Austen and music.

Instead, “it was very much a private activity,” Dooley said, adding that Austen “could never be prevailed upon to play in public”. Austen shared her love of music with family, however, including her nieces and Eliza, her cousin and sister-in-law. Some scholars believe that Eliza hosted a musical soiree at her home in 1811 to celebrate the publication of Austen’s first novel, “Sense and Sensibility,” Dooley said.

A sheet music collection was like the personal playlist of Austen’s day, offering a glimpse into private listening habits and tastes at a time when the trendy square piano had set off an explosion in domestic music-making. The more than 600 pieces in the Austen family collection reflect the popular music of the day, including Joseph Haydn, Domenico Corri and Ignaz Pleyel. But the collection also reveals the novelist’s eclectic taste and love of storytelling.

Austen meticulously copied out some scores by hand, including the keyboard music for emotional tales of love and loss in the Irish or Scottish folk traditions; ‘La Marseillaise’, the French revolutionary rallying cry; and a counterrevolutionary French ballad that was “quite seditious at the time,” said Dooley, who has catalogued the collection. Another melodramatic song describes a heartbroken woman called ‘Crazy Jane’, which it is easy to imagine was a bit of a family joke.

Outside the home, Austen heard music at the theatre, balls and concerts. At the start of the 19th century, there wasn’t yet the culture of virtuosic solo performers selling tickets that emerged as the 1800s progressed. Instead, people often went to concerts “to see and to be seen”, said Laura Klein, a Colorado-based musicologist and the creator of ‘The Jane Austen Playlist’, a digital collection of music and performances.

“Up to this point, the amateur musician was often as highly skilled as the professional,” Klein said. When Austen’s letters recounted a recent concert, the writer (a proud amateur herself) was sometimes cutting in her assessment of the professionals. In one from 1811, Klein said, Austen commented dryly that the performers “did what they were paid to do.”

Austen seems, more than anything, to have played for the love of music. But her novels show that musicianship could also be an obligation for young women.

In the Regency-era marriage market, it was a desirable accomplishment to be able to entertain a prospective husband’s guests. The piano, along with the harp, was seen as a female instrument, Timbs said, allowing the player to “sit elegantly” and subtly show off her physique to an assembled audience.

Klein said she often wondered why few — if any — of Austen’s heroines are especially musically gifted, given the novelist’s own lifelong practice and how present music-making is in her books.

The answer could be Austen’s appreciation of authenticity, Klein said. In one scene in ‘Pride and Prejudice’, Lizzy Bennet plods away at the piano after a dinner. She acknowledges to an attendant Mr Darcy that she does not play as well as other young ladies, and she also comments on his reluctance to dance at a recent ball. “We neither of us perform to strangers,” Mr Darcy says with a rare smile.

What draws Lizzy and Mr Darcy together is quite different, we are being told, from the typical arithmetic of the marriage market. In moments like this, Klein said, Austen was “pushing against this idea of accomplishment” as defining a woman’s value and therefore reducing music to “a bargaining chip”.

Only one song is mentioned by name in Austen’s novels — the sad love song “Robin Adair,” which Jane Fairfax plays in ‘Emma’ — but the music Austen played and heard shaped her writing. The rhythm and musicality of her prose reflect this (reading an Austen novel aloud is “almost like singing”, Dooley said) and so do some of her narratives.

Austen’s early writing, compiled as her ‘Juvenilia’, satirized the lyrics of popular, sentimental love songs of the day; ‘Sense and Sensibility’, in which the roguish John Willoughby abandons Marianne Dashwood and eventually marries a wealthier woman, has a similar plot to the ballad ‘Colin and Lucy’, which was in the Austen music collection, Dooley said.

Whether you listen to a performance on a square piano or through headphones, delving into Austen’s songs “brings the music to life in a really unique way,” Klein said. “It also brings the novels to life.”

–New York Times

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.