How serious is monkeypox?

By Knvul Sheikh

Health officials are tracking more than 100 cases of confirmed or suspected monkeypox that have appeared in countries where the disease does not typically occur, including Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States.

On Sunday (22), President Joe Biden addressed the highly unusual cases, stating that “it is a concern in the sense that if it were to spread it would be consequential.”

After more than two years of living through a pandemic, it is understandable that the news of a new virus spreading across the globe could cause alarm, but health experts say that monkeypox is unlikely to create a scenario similar to that of the coronavirus, even if more cases are found.

“As surveillance expands, we do expect that more cases will be seen. But we need to put this into context because it’s not COVID,” Dr Maria Van Kerkhove, the World Health Organization’s technical lead on COVID-19, said in a live online Q&A on Monday (23).

Monkeypox is not a new virus, and it is not spread in the same way as the coronavirus, so we asked experts for a better understanding of the pathogen — and how the disease it causes is different from COVID-19.

How contagious is monkeypox?

People typically catch monkeypox by coming into close contact with infected animals. That can be through an animal bite, scratch, bodily fluids, faeces or by consuming meat that isn’t cooked enough, said Ellen Carlin, a researcher at Georgetown University who studies zoonotic diseases that are transmitted from animals to humans.

Although it was first discovered in laboratory monkeys in 1958, which gives the virus its name, scientists think rodents are the main carriers of monkeypox in the wild. It is primarily found in Central and West Africa, particularly in areas close to tropical rainforests — and rope squirrels, tree squirrels, Gambian pouched rats and dormice have all been identified as potential carriers.

“The virus has probably been circulating in these animals for a very, very long time,” Carlin said. “And for the most part, it has stayed in animal populations.”

The first human case of monkeypox was detected in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Since then, the virus has periodically caused small outbreaks, though most have been limited to a few hundred cases in 11 African countries.

A handful of cases have made it to other continents, brought by travellers or the import of exotic animals that passed the virus to house pets and then to their owners.

But human-to-human transmission of monkeypox virus is pretty rare, Van Kerkhove said. “Transmission is really happening from close physical contact, skin-to-skin contact. So it’s quite different from COVID in that sense.”

The virus can also spread by touching or sharing infected items like clothing and bedding, or by the respiratory droplets produced by sneezing or coughing, according to the WHO.

That may sound eerily familiar because in the early days of the pandemic many experts said that the coronavirus also had little human-to-human transmission beyond respiratory droplets and contaminated surfaces. Later research showed that the coronavirus can spread through much smaller particles called aerosols with the ability to travel distances greater than 6 feet. But that doesn’t mean the same will turn out to be true for the monkeypox virus, said Luis Sigal, an expert in poxviruses at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

The coronavirus is a tiny, single-stranded RNA virus, which may have aided its ability to become airborne. The monkeypox virus, however, is made of double-stranded DNA, which means that the virus itself is much larger and heavier and unable to travel as far, Sigal said.

Other routes of monkeypox transmission include from mother to foetus via the placenta or during close contact during and after birth.

The majority of cases this year have been in young men, many of whom self-identified as men who have sex with men, though experts are cautious about suggesting that monkeypox transmission may occur through semen or other bodily fluids exchanged during sex. Instead, contact with infected lesions during sex may be a more plausible route.

“This is not a gay disease, as some people in social media have attempted to label it,” Dr Andy Seale, an adviser with the WHO’s HIV, Hepatitis and Sexually Transmitted Infections Program, said during Monday’s Q&A. “Anybody can contract monkeypox through close contact.”

What are the symptoms, and how bad can a monkeypox infection get?

Monkeypox is part of the same family of viruses as smallpox, but it is typically a much milder condition, according to the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. On average, symptoms appear within six to 13 days of exposure but can take up to three weeks. People who get sick commonly experience a fever, headache, back and muscle aches, swollen lymph nodes and general exhaustion.

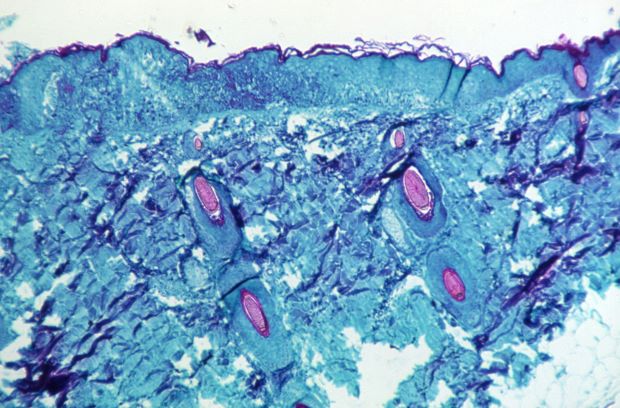

About one to three days after getting a fever, most people also develop a painful rash that is characteristic of poxviruses. It starts with flat red marks that become raised and filled with pus over the course of the next five to seven days. The rash can start on a patient’s face, hands, feet, the inside of their mouth or on their genitals, and progress to the rest of the body. (While chickenpox causes a similar-looking rash, it is not a true poxvirus but is caused by the unrelated varicella-zoster virus.)

Once an individual’s pustules scab over, in two to four weeks, they are no longer infectious, said Angela Rasmussen, a virus expert at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada.

Children and people with underlying immune deficiencies may have more severe cases, but monkeypox is rarely fatal. While one strain found in Central Africa can kill up to 10% of infected individuals, estimates suggest that the version of the virus currently circulating has a fatality rate of less than 1%.

And the easily identifiable rash of monkeypox, as well as its earlier symptoms, could be considered beneficial. “One of the most challenging things about COVID has been that it can be spread asymptomatically or pre-symptomatically, by people who have no idea that they’re infected,” Rasmussen said. “But with monkeypox it doesn’t appear that there is any pre-symptomatic transmission.”

Still, as the recent outbreak of cases has shown, there are plenty of opportunities to transmit monkeypox in the first few days of an infection, when symptoms are nonspecific, Rasmussen said.

Do I need to worry about a rising threat?

The good news is that there is no evidence yet to suggest that the monkeypox virus has evolved or become more infectious. DNA viruses like monkeypox are generally very stable and evolve extremely slowly compared to RNA viruses, Sigal said. Scientists are sequencing the viruses from recent cases to check for potential mutations, and will know soon if the infectiousness, severity or other characteristics have changed, he said. “But my expectation is that they will not be any different.”

Nevertheless, experts have some explanations for the recent increase in monkeypox cases. Research has shown that incidences of humans contracting viruses from contact with animals — also known as zoonotic spillovers — have become more common in recent decades. Increasing urbanization and deforestation means that humans and wild animals are coming into contact more often. Some animals that carry zoonotic viruses, like bats and rodents, have actually become more abundant, while others have expanded or adapted their habitats due to urban development and climate change.

“There’s more opportunities for relatively rare pathogens to get into new communities, find new hosts and travel to new places,” Rasmussen said.

Despite a brief pandemic lull, people are also traveling more frequently and to more parts of the world than they did just a decade ago. And while many of the new monkeypox cases are puzzling because patients did not have a history of direct travel to endemic countries in Africa, public health researchers may uncover an indirect travel connection as they race to complete contact tracing in the coming weeks.

“The main risk for people these days with regards to viruses remains COVID,” Rasmussen said. “The good news there is that a lot of the same measures that will reduce your risk of COVID — social distancing, wearing masks in public spaces, practicing good hand hygiene and surface disinfection — will also reduce your risk of getting monkeypox.”

What is the treatment for monkeypox?

If you get sick, the treatment for monkeypox generally involves symptom management. Two antiviral drugs — cidofovir and tecovirimat — and an intravenous antibody treatment originally developed for smallpox could be used to manage monkeypox as well, though they have only been studied in the lab and animal models.

There is also a vaccine that the Food and Drug Administration approved in 2019, for people 18 and older, that protects against smallpox and monkeypox. But health officials stopped routinely vaccinating Americans against smallpox in 1972, when the disease was eradicated in the United States, and smallpox vaccines and treatments are now stockpiled mainly for national security purposes.

“The sporadic monkeypox outbreaks that have occurred in the past haven’t been enough to warrant restarting the smallpox vaccination program,” Rasmussen said. Health officials in the U.S. and other countries may consider using some of the stockpiled vaccines in a “ring vaccination” strategy to prevent the spread of monkeypox from a patient to their health care providers and close contacts, she said.

If you have a new rash or are concerned about monkeypox, the CDC urges people to contact their health care provider. The agency has asked doctors to be on the alert for signs of the telltale rash and said potential monkeypox cases should be isolated and flagged to them. Doctors also should not limit their concerns to men who identify as gay or bisexual, or patients who have recently travelled to Central or West African countries.

-New York Times